2018 WL 1192933

Only the Westlaw citation is currently available.

Court of Appeals of Washington,

Division 3.

STATE of Washington, Respondent,

v.

Donald J. ZACK, Appellant.

No. 34926-8-III

|

Filed March 8, 2018

Appeal from Yakima Superior Court, Docket No: 16-1-01637-1, Honorable Richard H. Bartheld

Attorneys and Law Firms

Lise Ellner, Attorney at Law, PO Box 2711, Vashon, WA, 98070-2711, Skylar Texas Brett, Law Office of Skylar Brett, PO Box 18084, Seattle, WA, 98118-0084, for Appellant.

Joseph Anthony Brusic, Yakima County Prosecutor’s Office, 128 N 2nd St. Rm. 329, Yakima, WA, 98901-2621, David Brian Trefry, Yakima County Prosecutors Office, PO Box 4846, Spokane, WA, 99220-0846, Fronda Colleen Woods, Washington Attorney General Licensing and Administrative Law Division, 1125 Washington St. Se, PO Box 40110, Olympia, WA, 98504-0110, for Respondent.

Opinion

OPINION PUBLISHED IN PART

Korsmo, J.

Donald Zack appeals his conviction for third degree assault of a law enforcement officer, contending that the State of Washington did not retain jurisdiction to prosecute an Indian for any offenses committed within the boundaries of the Yakama Reservation. Interpreting the governor’s retrocession proclamation as he intended it, we conclude that the State retained jurisdiction to prosecute Mr. Zack for an offense occurring on deeded land and affirm the conviction.

FACTS

The salient facts are largely historic and will be discussed shortly. As to the facts of this incident, few are relevant to the analysis. Mr. Zack, who lives on the Yakama Reservation but is not an enrolled member of the tribe, was booked into the Toppenish City Jail. A jail officer then took him to the Toppenish City Hospital, property located on deeded (fee) land within the boundaries of the reservation, for treatment. While at the hospital, Mr. Zack assaulted the officer. The officer is not an Indian; Mr. Zack asserts that he is an Indian, although he is not an enrolled member of any tribe.

In general terms, Washington responded to Public Law 280 by asserting civil and criminal jurisdiction over Indians acting on deeded or fee lands, but it declined to assert jurisdiction over Indians while on tribal or trust land.1 RCW 37.12.010. The history of Washington’s assertion of jurisdiction over the Yakama Reservation is discussed in Washington v. Confederated Bands & Tribes of Yakima Indian Nation, 439 U.S. 463, 465-76, 99 S.Ct. 740, 58 L.Ed. 2d 740 (1979).2 Subsequently, Congress acted to encourage states to withdraw some of their assertions of authority in favor of tribal authority. 25 U.S.C. § 1323 (1968).

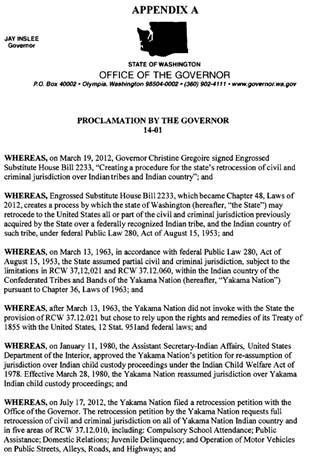

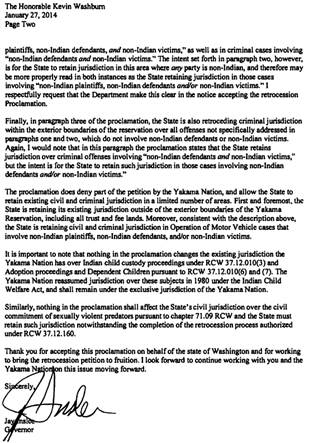

Washington responded by passing legislation authorizing the Governor, upon the request of a tribe, to enter into negotiations with any tribe desiring to assume jurisdiction from Washington State. RCW 37.12.160. Governor Jay Inslee, after negotiations with the Yakama Nation, issued Proclamation 14-01 on January 17, 2014.3 The proclamation returned complete civil and criminal jurisdiction to the tribe in four specific subject areas, returned some civil and criminal jurisdiction arising from the operation of motor vehicles on public thoroughfares, and noted some subject areas in which no changes were being made. With respect to the question of criminal jurisdiction, the proclamation states in paragraph 3:

3. Within the exterior boundaries of the Yakama Reservation, the State shall retrocede, in part, criminal jurisdiction over all offenses not addressed by Paragraphs 1 and 2. The State retains jurisdiction over criminal offenses involving non-Indian defendants and non-Indian victims.

(emphasis added). See Appendix A at 2.

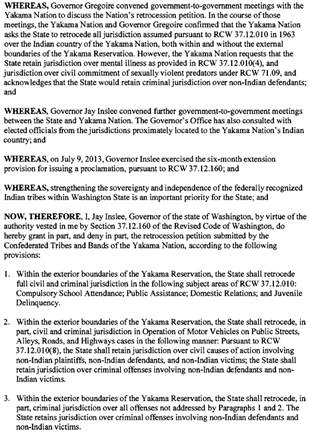

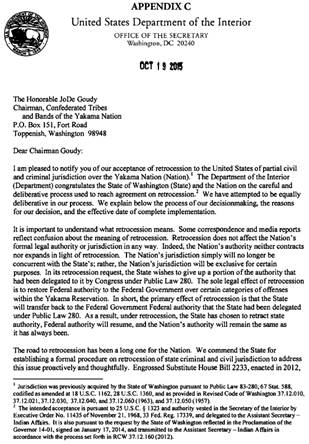

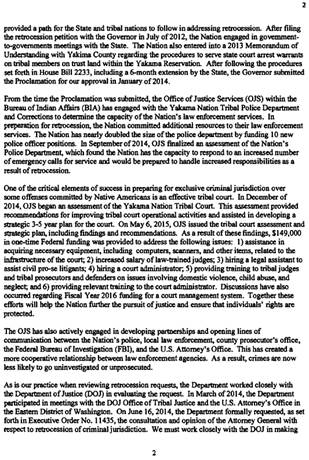

In his formal conveyance of the proclamation to the Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs, Governor Inslee wrote a clarification to assure that the underscored language was understood to mean that the State was retaining jurisdiction in criminal cases where either the defendant or the victim was not an Indian. See Appendix Bat 2. In accepting the State’s retrocession of jurisdiction, the Department of Interior accepted only the proclamation and not the interpretation placed on it by the Governor. See Appendix C at 5. In the view of the Assistant Secretary, the proclamation was unambiguous and did not need interpretation, but that the courts would resolve the matter if needed. Id.

The State filed a charge of third degree assault. Mr. Zack moved to dismiss the prosecution for lack of jurisdiction, alleging that he was an Indian and that under the terms of the proclamation, the State could not act against him because it had retained jurisdiction only of criminal matters that involved both a non-Indian defendant and a non-Indian victim. Evidence of Mr. Zack’s Indian heritage was presented and argued to the trial court, but the judge made no determination of that status.4

Instead, the court interpreted the proclamation to mean that the State retained jurisdiction if either the defendant or the victim was a non-Indian. The motion to dismiss was denied. Mr. Zack then stipulated to admission of the police reports and was convicted as charged at a bench trial. He timely appealed to this court.

ANALYSIS

This appeal presents two issues. In the published portion of this opinion, we address the interpretation of the retrocession proclamation. In the unpublished portion, we address Mr. Zack’s contention that the evidence was insufficient to support the conviction.

Retrocession Proclamation

The jurisdiction issue turns on the meaning of the Governor’s proclamation, with the dispositive question being the meaning of the word “and.” In context, the word “and” is used in a list and should be read in the disjunctive; to do otherwise would render the proclamation internally inconsistent and nonsensical. Thus, we agree with the Governor that the meaning of the word “and” in this instance is “and/or.”

Whether a state court has jurisdiction over crimes committed on reservation land is a question of law subject to de novo review. State v. Squally, 132 Wash.2d 333, 340, 937 P.2d 1069 (1997). We have been unable to find clear Washington authority addressing construction of a gubernatorial proclamation.5 Since this particular proclamation, like many before it, flows from a statutory grant of authority to enter into negotiations upon the request of a tribe and to return jurisdiction to the tribe when agreeable, we deem it appropriate to treat the proclamation as if it were legislative in origin.6

When addressing a question of pure statutory interpretation or of the meaning of the constitution, an appellate court also engages in de novo review. State v. Bradshaw, 152 Wash.2d 528, 531, 98 P.3d 1190 (2004).7 The goal of statutory interpretation “is to discern and implement” legislative intent. Lowy v. PeaceHealth, 174 Wash.2d 769, 779, 280 P.3d 1078 (2012). In some circumstances, “legislative intent” may also include the Governor’s intent: “Where the Governor has vetoed part of a statute, the Governor has acted as part of the Legislature and we consider gubernatorial intent as well.” In re Marriage of Maples, 78 Wash.App. 696, 701-02, 899 P.2d 1 (1995) (citing State ex rel. Royal v. Yakima County Comm’rs, 123 Wash.2d 451, 462-63, 869 P.2d 56 (1994) ). Accord State v. Reis, 183 Wash.2d 197, 212-13, 351 P.3d 127 (2015); Hallin v. Trent, 94 Wash.2d 671, 677, 619 P.2d 357 (1980); Shelton Hotel Co. v. Bates, 4 Wash.2d 498, 506, 104 P.2d 478 (1940). In the circumstance of a gubernatorial proclamation that carries out a legislative grant of authority, we likewise consider it appropriate to treat the Governor’s express statement of intent as a species of “legislative intent” for the purpose of construing the Governor’s meaning.8

A court begins its inquiry into determination of intent by looking at the plain meaning of the statute as expressed through the words themselves. Tesoro Ref. & Mktg. Co. v. Dep’t of Revenue, 164 Wash.2d 310, 317, 190 P.3d 28 (2008). If the statute’s meaning is plain on its face, the court applies the plain meaning. State v. Armendariz, 160 Wash.2d 106, 110, 156 P.3d 201 (2007).9 A provision is ambiguous if it is reasonably subject to multiple interpretations. State v. Engel, 166 Wash.2d 572, 579, 210 P.3d 1007 (2009). Only if the language is ambiguous does the court look to aids of construction, such as legislative history. Armendariz, at 110-11, 156 P.3d 201. When interpretation is necessary, the legislation “must be interpreted and construed so that all the language used is given effect, with no portion rendered meaningless or superfluous.” Whatcom County v. City of Bellingham, 128 Wash.2d 537, 546, 909 P.2d 1303 (1996).

Initially, we do conclude that the challenged language of paragraph three is potentially ambiguous. Although the word “and” typically is used in the conjunctive sense of joining two or more items, it need not be so applied:

Where the plain language and intent of the statute so indicate, “[t]he disjunctive ‘or’ and conjunctive ‘and’ may be interpreted as substitutes.” Mount Spokane Skiing Corp. v. Spokane County, 86 Wn. App. 165, 174, 936 P.2d 1148 (1997); see also CLEAN v. City of Spokane, 133 Wn.2d 455, 473-74, 947 P.2d 1169 (1997); Bullseye Distrib. LLC v. State Gambling Comm’n, 127 Wn. App. 231, 238-40, 110 P.3d 1162 (2005).

State v. McDonald, 183 Wash.App. 272, 278, 333 P.3d 451 (2014). This long has been a rule of construction. State v. Tiffany, 44 Wash. 602, 604, 87 P. 932 (1906) (“No doubt or is sometimes construed to mean and, and vice versa, in statutes, wills, and contracts.”). There simply are times where the meaning of the word “and” is unclear and Mr. Zack’s argument convinces us this is one of those occasions.10

¶ 14 Here, it is appropriate to treat “and” as “or” in order to avoid rendering a portion of the proclamation meaningless. After noting the return of jurisdiction in paragraphs one and two, the proclamation states that all other matters of criminal jurisdiction are returned “in part,” but that the State was retaining “criminal offenses involving non-Indian defendants and non-Indian victims.” Appendix A at 2. Mr. Zack’s construction of that phraseology would mean that the only type of case the State now could prosecute would require the involvement of non-Indian defendants who victimized other non-Indians on fee land. However, Public Law 280 and RCW 37.12.010 were only about the assertion of State jurisdiction over Indians. The State already had authority to prosecute non-Indians for offenses committed on deeded lands prior to the enactment of Public Law 280. E.g., Draper v. United States, 164 U.S. 240, 17 S.Ct. 107, 41 L.Ed. 419 (1896) (only state had authority to try non-Indian for murder of non-Indian); State v. Lindsey, 133 Wash. 140, 144-45, 233 P. 327 (1925) (non-Indian manufacturer of liquor); State v. Batten, 17 Wash.App. 428, 430, 563 P.2d 1287 (1977) (murder of non-Indian by non-Indian). Excluding Indians from prosecution in all cases, as Mr. Zack contends occurred in this proclamation, would mean that the Governor intended to return all of the criminal jurisdiction the State assumed by RCW 37.12.010 and the words “in part” would be rendered meaningless because there would have been total rather than partial retrocession.11

In addition, the proclamation also would be rendered nonsensical and in excess of the Governor’s statutory authority. Read literally, as Mr. Zack argues we must do, the proclamation would only apply to multiple defendants committing offenses against multiple victims. Apparently a single defendant acting on his own could not be prosecuted for offending against either a single victim or against multiple victims. In addition, even multiple defendants presumably could not be prosecuted if they acted in concert against only a single victim. Finally, victimless crimes could not be prosecuted at all if the only jurisdiction the State was retaining involved multiple defendants acting against multiple victims. This interpretation is nonsensical.

The Governor also was not authorized by RCW 37.12.160 to return any jurisdiction other than that assumed by RCW 37.12.010. Asserting or removing State jurisdiction over non-Indians is not within the scope of Public Law 280 or RCW 37.12.010. Interpreting the proclamation as Mr. Zack insists would result in the Governor engaging in an ultra vires action.

For all of these reasons, we reject Mr. Zack’s contention. Standard rules of construction simply preclude his interpretation of the proclamation. In addition, we also have the Governor’s clarification of his intent contained in the letter in Appendix B. Although we think the Governor’s interpretation is strong evidence of his intent, it is not controlling over our decision any more than a legislative statement of intent controls an issue of statutory construction. Nonetheless, it is significant contemporaneous evidence of the purpose behind the Governor’s choice of language. It fully supports our decision.

Thus, we conclude that the State retained jurisdiction to prosecute this assault against a non-Indian occurring on deeded land within the boundaries of the Yakama Reservation. The trial court correctly denied the motion to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction.

A majority of the panel having determined that only the foregoing portion of this opinion will be printed in the Washington Appellate Reports and that the remainder having no precedential value shall be filed for public record pursuant to RCW 2.06.040, it is so ordered.

Unpublished Text Follows

Sufficiency of the Evidence

Mr. Zack also contends that the evidence was insufficient to support the conviction, arguing that the victim was a corrections officer rather than a law enforcement officer. We disagree.

Well settled standards govern this challenge. Whether or not sufficient evidence has been produced to support a criminal conviction presents a question of law under the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307, 317-19, 99 S. Ct. 2781, 61 L.Ed. 2d 560 (1979). Specifically, Jackson stated the test for evidentiary sufficiency under the federal constitution to be “whether, after viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the prosecution, any rational trier of fact could have found the essential elements of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt.” Id. at 319, 99 S.Ct. 2781. Washington follows the Jackson standard. State v. Green, 94 Wash.2d 216, 221-22, 616 P.2d 628 (1980) (plurality opinion); Id. at 235, 616 P.2d 628 (Utter, C.J., concurring).

A person commits the crime of third degree assault if he, “Assaults a law enforcement officer or other employee of a law enforcement agency who was performing his or her official duties at the time of the assault.” RCW 9A.36.031(1)(g). The legislature has not defined the terms “law enforcement officer” or “law enforcement agency” for purposes of this statute; neither are those terms found in the general definition statutes of the criminal code. See RCW 9A.04.110.12 This court has previously determined that the Department of Corrections is a law enforcement agency. See McLean v. Dep’t of Corr., 37 Wash.App. 255, 680 P.2d 65 (1984) (construing phrase in felon employment disqualification statute).13 We think the reasoning of that case is equally applicable here. More importantly, we believe that a fact-finder would contemplate that incarcerating an offender is just as much a law enforcement function as investigating a crime and arresting a suspect. Accordingly, we believe the evidence is sufficient to support the determination that the officer was an employee of a law enforcement agency.

Cost Issues

Although he had not complied with our general order, Mr. Zack asks this court not to impose appellate costs against him. Since the State indicates that it will not file a cost bill, we will not further address this request.

Mr. Zack also challenges the trial court’s imposition of $200 incarceration costs without first determining his ability to pay them. The State indicates that it will obtain an order striking that cost award from the judgment and sentence. We remand the case for that purpose.

End of Unpublished Text

I CONCUR:

Siddoway, J.

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX B

APPENDIX C

Fearing, C.J. (concurring)

I concur in all rulings of the majority, including the majority’s reading of the language in paragraph 3 of Governor Jay Inslee’s Proclamation 14-01 of January 17, 2014. Sometimes the word “and” means the disjunctive rather than the conjunctive. Bullseye Distributing LLC v. State Gambling Commission, 127 Wash.App. 231, 239, 110 P.3d 1162 (2005). In the context of paragraph 3 of the proclamation, we must read the word “and” between “non-Indian defendants” and “non-Indian victims” in the conjunctive because the paragraph declares a partial retrocession. If we read the word “and” in the disjunctive, the proclamation would announce a full retrocession. We must read a document by according all words some meaning. State v. Roggenkamp, 153 Wash.2d 614, 624, 106 P.3d 196 (2005).

I disagree with the majority’s utilization of Governor Jay Inslee’s January 27, 2014, letter to the United States Department of the Interior to assist in discerning the intent of Proclamation 14-01. The Department of the Interior did not deem the Governor’s letter as binding on the department. We determine the measure of retrocession by the extent of acceptance by the Department of the Interior, not the intent of the State to the extent the State expresses that intent in a document not accepted by the department. United States v. Lawrence, 595 F.2d 1149, 1151 (9th Cir. 1979); Oliphant v. Schlie, 544 F.2d 1007 (9th Cir. 1976), rev’d on other grounds sub nom. Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191, 98 S.Ct. 1011, 55 L.Ed. 2d 209 (1978); Omaha Tribe of Nebraska v. Village of Walthill, 334 F.Supp. 823 (D. Neb. 1971), aff’d sub nom. Omaha Tribe of Nebraska v. Village of Walthill, Nebraska, 460 F.2d 1327 (8th Cir. 1972).

I CONCUR.

All Citations

--- P.3d ----, 2018 WL 1192933

Footnotes |

|

See, e.g., State v. Sohappy, 110 Wash.2d 907, 757 P.2d 509 (1988) (no State jurisdiction over Indian acting on tribal lands or in-lieu sites). Nothing in the Governor’s proclamation affects Indians acting on tribal lands. Sohappy remains good law. |

|

Yakima Indian Nation recognized that Washington had assumed criminal jurisdiction over fee lands to the full extent permitted by Public Law 280. 439 U.S. at 498, 99 S.Ct. 740. |

|

A copy of the proclamation is attached as Appendix A. |

|

Mr. Zack testified that he is 15/32 Indian (7/32 Yakama, 1/4 Muscogee Creek) and is ineligible to enroll as a member of the Yakama Nation; he claims eligibility to enroll with the Muscogee Creek Tribe in Oklahoma, but has not done so. Mr. Zack has received medical and dental benefits through the federal Indian Health Services for his entire life, participates in treaty fishing with the tribe, and has held jobs at the tribal casino. Mr. Zack also testified that he has spent some time in the tribal jail, but is no longer allowed there and instead is held by Yakima County. The State alleged in its trial court briefing that in 2014 the tribe turned Mr. Zack over to the State for prosecution of a trespass case that occurred on tribal trust land. |

|

In Squally, the court’s opinion makes reference to the “broad language” of the Governor’s proclamation, a factor of significance to the court’s resolution of the jurisdictional issue presented by that case. Squally, 132 Wash.2d at 343, 937 P.2d 1069. However, the court never stated a standard of review applicable to the proclamation nor did it suggest whether the Governor’s language was accorded any special weight in the court’s analysis. |

|

Due to the absence of case or statutory authority on the topic, the attorney general issued an opinion indicating it was appropriate to interpret a gubernatorial proclamation in the same manner as construing a statute. 1957 Op. Att’y Gen. No. 74, at 3. |

|

The same standard applies to review of administrative regulations. Skinner v. Civil Serv. Comm’n, 168 Wash.2d 845, 849, 232 P.3d 558 (2010). |

|

We note that the federal courts look to presidential intent when construing the meaning of a proclamation. E.g., Diaz v. United States, 222 U.S. 574, 578, 32 S.Ct. 184, 56 L.Ed. 321 (1912) (“It could not have been the intention of the President to prevent the seizure of property when necessary for military uses, or to prevent its confiscation or destruction.”); Bailey v. Richardson, 182 F.2d 46, 52 (D.C. Cir. 1950) (“The question is not what the word might mean otherwise or elsewhere; the question is simply what the President used it to mean.”), aff’d by an equally divided court, Carlson v. Landon, 341 U.S. 918, 71 S.Ct. 744, 95 L.Ed. 1353 (1951), abrogated by Bd. of Regents of State Colls. v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564, 571 & n.9, 92 S.Ct. 2701, 33 L.Ed. 2d 548 (1972). |

|

Similarly, words in a constitutional provision are given their common and ordinary meaning. State ex rel. Albright v. City of Spokane, 64 Wash.2d 767, 770, 394 P.2d 231 (1964). |

|

Indeed, in Yakima Indian Nation, the Supreme Court rejected an argument that the phrase “assumption of civil and criminal jurisdiction” in Public Law 280 had to be read conjunctively. 439 U.S. at 496-97, 99 S.Ct. 740. |

|

Examples of the kinds of cases the State was returning would include most drug and hunting offenses committed on fee lands (along with all other victimless crimes), as well as crimes committed by an Indian against an Indian on fee land. Since the State had no jurisdiction over Indians acting on tribal land, those situations are not changed by the proclamation. |

|

“Law enforcement officer” is defined in RCW 9A.76.020(2) (Obstructing a law enforcement officer), which states, “ ‘Law enforcement officer’ means any general authority, limited authority, or specially commissioned Washington peace officer ... and other public officers who are responsible for enforcement of fire, building, zoning, and life and safety codes.” |

|

Mr. Zack attempts to distinguish McLean by pointing to the subsequent enactment of the custodial assault statute, RCW 9A.36.100(1)(b), and suggesting that was the more appropriate charge for this case. However, the assault occurred away from the detention facility, making that statute inapplicable to this case. |

|