2019 WL 1999298

Only the Westlaw citation is currently available.

United States Court of Appeals, Tenth Circuit.

DINE CITIZENS AGAINST RUINING OUR ENVIRONMENT; San Juan Citizens Alliance; WildEarth Guardians; Natural Resources Defense Council, Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

David BERNHARDT, in His Official Capacity as Acting Secretary of the United States Department of the Interior; United States Bureau of Land Management, an Agency Within the United States Department of the Interior; Neil Kornze, in His Official Capacity as Director of the United States Bureau of Land Management, Defendants-Appellees,

and

DJR Energy Holdings, LLC; BP America Production Company; American Petroleum Institute; Anschutz Exploration Corporation; Enduring Resources IV, LLC, Intervenor Defendants-Appellees,

and

ConocoPhillips Company; Burlington Resources Oil & Gas Company LP, Intervenor Defendants.

All Pueblo Council of Governors; National Trust for Historic Preservation; Navajo Allottees; Alice Benally; Lilly Comanche; Virginia Harrison; Samuel Harrison; Dolora Hesuse; Verna Martinez; Loyce Phoenix, Amici Curiae.

No. 18-2089

|

FILED May 7, 2019

Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of New Mexico (D.C. No. 1:15-CV-00209-JB-LF)

Attorneys and Law Firms

Samantha Ruscavage-Barz, WildEarth Guardians, Santa Fe, New Mexico (Kyle J. Tisdel, Western Environmental Law Center, Taos, New Mexico, with her on the briefs), appearing for Appellants.

Avi Kupfer, U.S. Department of Justice, Environment & Natural Resources Division, Washington, D.C. (Michael C. Williams, Of Counsel, Attorney-Advisor, Office of the Solicitor, U.S. Department of the Interior, Clare M. Boronow, and Mark R. Haag, U.S. Department of Justice, Environment & Natural Resources Division, Washington, D.C., on the brief), for the Defendants-Appellees.

Hadassah M. Reimer, Holland & Hart LLP, Jackson, Wyoming (Stephen G. Masciocchi, and John F. Shepherd, Holland & Hart LLP, Denver, Colorado, Bradford Berge, Holland & Hart LLP, Santa Fe, New Mexico, Rebecca W. Watson, Welborn Sullivan Meck & Tooley, P.C., Denver, Colorado, Stephen Rosenbaum, Covington & Burling, LLP, Washington, D.C., and Jon J. Indall, Comeau Maldegen Templeman & Indall LLP, Santa Fe, New Mexico, with her on the brief), appearing for Intervenors-Appellees.

Before BRISCOE, McKAY, and HOLMES, Circuit Judges.

Opinion

BRISCOE, Circuit Judge.

In this case, we are asked to decide whether the Bureau of Land Management violated the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in granting more than 300 applications for permits to drill horizontal, multi-stage hydraulically fracked wells in the Mancos Shale area of the San Juan Basin in northeastern New Mexico. Appellants1 sued the Secretary of the Department of the Interior, the Bureau of Land Management, and the Secretary of the BLM, alleging that the BLM authorized the drilling without fully considering its indirect and cumulative impacts on the environment or on historic properties. The district court denied Appellants a preliminary injunction, and we affirmed that decision in 2016. After merits briefing, the district court concluded that the BLM had not violated either NHPA or NEPA and dismissed Appellants’ claims with prejudice. Appellants now appeal.

We have jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1291 and affirm in part, reverse in part, and remand with instructions.

I

The San Juan Basin is a large geographic region in the southwestern United States, including part of New Mexico. Drilling for oil and gas has occurred in the Basin for more than sixty years, and the Basin is currently one of the most prolific sources of natural gas in the country. The Basin includes both public and private lands. Many of the public lands and resources fall under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Land Management’s Farmington Field Office in New Mexico, which manages these lands and resources under its published Resource Management Plan.

In 2000, the BLM initiated the process of revising its existing RMP, which had been published in 1988. As part of this process, the BLM contracted with the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Geology to develop a “reasonably foreseeable development scenario,” or RFDS, to predict the foreseeable oil and gas development likely to occur over the next twenty years. Based on historic production data and available geologic and engineering evidence, the RFDS estimated that 9,970 new oil and gas wells would be drilled on federally managed lands in the New Mexico portion of the San Juan Basin during this time period. Of these wells, the RFDS estimated that more than forty percent would be “Dakota, Mancos” gas wells—wells that could produce gas from both the Mancos geologic horizon and the Dakota geologic horizon that lies below it. The RFDS estimated that only 180 new oil wells would be drilled in the Mancos Shale, due to the fact that most reservoirs in the Mancos Shale were approaching depletion under then-current technologies, but it noted that there is excellent potential for the Mancos to be further evaluated.

In 2003, the BLM issued its Proposed Resource Management Plan and Final Environmental Impact Statement ( [2003 EIS] ). In this document, the BLM referred to the predictions and analysis contained in the RFDS in order to assess four proposed alternatives for managing federal lands in the San Juan Basin, including the “balanced approach” the agency ultimately decided to adopt. Under this balanced approach, the BLM analyzed the cumulative impacts of an estimated 9,942 new wells in the San Juan Basin—approximately the same number predicted in the 2001 RFDS—by looking at, for instance, the likely air quality impacts from the drilling and operation of this many new wells in the region. The [2003 EIS] did not discuss specific sites or approve any individual wells, although it assumed the majority of new wells would be drilled in the high development area in the northern part of the managed area. The BLM issued its final RMP, adopting the Alternative D balanced approach, in December 2003.

Diné Citizens Against Ruining Our Env’t v. Jewell (Diné II), 839 F.3d 1276, 1279–80 (10th Cir. 2016) (citations omitted).

Although the 2003 EIS analyzed oil and gas drilling in the San Juan Basin generally, operators wanting to drill new wells in the area must seek and receive approval for specific drilling via an application for a permit to drill (APD) submitted to the BLM. When the BLM receives an APD, it prepares an environmental assessment (EA) examining the environmental impacts of the proposed drilling. The EA must include an analysis of the direct, indirect, and cumulative effects of the proposed drilling. See 40 C.F.R. §§ 1508.7, 1508.8. The EA process results in one of three outcomes: (1) a conclusion that the proposed action would result in a significant environmental impact, necessitating an EIS, (2) a conclusion that the proposed action would not result in a significant environmental impact—a “finding of no significant impact” (FONSI), or (3) a conclusion that the proposed action will not go forward. 43 C.F.R. § 46.325. Even if a proposed action will have significant effects, the EA may still result in a FONSI if it is tiered to a broader environmental analysis that fully analyzed those significant effects. Id. § 46.140(c).

Beginning in 2010, the BLM began receiving APDs for drilling in the Mancos Shale. Development interest in the area increased quickly, and between early 2012 and April 2014, seventy new wells were completed in the Mancos Shale area. In 2014, recognizing the potential for additional Mancos Shale development, the BLM had a new RFDS prepared to evaluate the Mancos Shale’s potential for oil and gas development. The 2014 RFDS estimates that full development of the Mancos Shale would result in 3,960 new wells.

The 2014 RFDS predicts that new drilling in the Mancos Shale will be done largely, if not entirely, by horizontal drilling and multi-stage hydraulic fracturing. “A horizontally drilled well starts as a vertical or directional well, but then curves and becomes horizontal, or nearly so, allowing the wellbore [i.e., drilled hole] to follow within a rock stratum for significant distances and thus greatly increase the volume of a reservoir opened by the wellbore.” Wyoming v. Zinke, 871 F.3d 1133, 1137 (10th Cir. 2017) (alteration in original) (quotations omitted). Hydraulic fracturing is a process designed to “maximize the extraction” of oil and gas resources. JA1912. Fluids, usually water with chemical additives, “are pumped into a geologic formation at high pressure.” Id. When the pressure “exceeds the rock strength,” it creates or enlarges fractures from which oil and gas can flow more freely. Id. After the fractures are created, a “propping agent (usually sand) is pumped into the fractures to keep them from closing.” Id.

As we noted previously,

These new drilling techniques have greatly increased access to oil and gas reserves that were not previously targeted for development and have given rise to much higher levels of development in the Mancos Shale than the BLM previously estimated and accounted for. Moreover, horizontal drilling and multi-stage fracturing may have greater environmental impacts than vertical drilling and older fracturing techniques.

Diné II, 839 F.3d at 1283.

Hydraulic fracturing is common in the San Juan Basin and has been used there in some form since the 1950s. Horizontal drilling, however, is relatively new. At the time the 2003 EIS issued, “[h]orizontal drilling [wa]s possible but not [then] applied in the San Juan Basin due to poor cost[-]to[-]benefit ratio.” JA746. The environmental impacts considered in the 2003 EIS were therefore based on the impacts associated with vertical drilling, not horizontal drilling. But the 2003 EIS noted that “[i]f horizontal drilling should prove economically and technically feasible in the future, the next advancement in horizontal well technology could be drilling multi-laterals or hydraulic fracturing horizontal wells.” Id.

Since the 2003 EIS issued, 3,945 of the 9,942 contemplated vertical wells have been drilled in the San Juan Basin. The BLM continues to receive and approve APDs for horizontal Mancos Shale wells. Appellants’ initial petition in the district court challenged “at least 130” Mancos Shale APDs approved by the BLM. JA2449. Over the course of this litigation, Appellants amended their petition three times to account for additional granted APDs. Their final petition challenged “at least 351” APDs.2 JA2701.

In 2015, Appellants filed their first Petition for Review of Agency Action (Petition) in district court, challenging the BLM’s issuance of APDs as violative of NEPA and NHPA. Appellants named as defendants the Secretary of the United States Department of the Interior, BLM, and the Director of BLM (collectively, Federal Appellees). A group of oil companies (DJR Energy Holdings, LLC, BP America Production Company, American Petroleum Institute, Anschutz Exploration Corporation, and Enduring Resources IV, LLC), each of which owns leases or drilling permits in the Mancos Shale intervened as defendants (collectively, Intervenor Appellees).

Appellants moved for a preliminary injunction, which the district court denied. See Diné Citizens Against Ruining Our Env’t v. Jewell (Diné I), No. CIV 15-0209, 2015 WL 6393843 (D.N.M. Sept. 16, 2015). This court upheld the denial on appeal. Diné II, 839 F.3d 1276. In district court, Appellants amended their Petition three times to add additional challenged APDs. Appellants’ operative Third Supplemented Petition alleges, as relevant on appeal: (1) a NEPA violation for improperly tiering the EAs to the 2003 EIS; (2) a NEPA violation for failing to prepare an EIS or supplement an existing EIS; and (3) a NHPA violation for failing to complete Section 106 consultation. Appellants sought vacatur of all the challenged APDs and an injunction against all “future horizontal drilling or hydraulic fracturing in the Mancos Shale” until the BLM complied with NHPA and NEPA. JA2743.

In April 2017, Appellants sought judgment in the district court. On April 23, 2018, the district court ruled against Appellants and dismissed their claims with prejudice. The district court made the following relevant rulings: (1) Appellants have standing to pursue their claims; (2) Appellants do not establish a NEPA violation; and (3) Appellants do not establish a NHPA violation.

Appellants timely appealed, raising two issues. First, they contend that the BLM violated NHPA because it “failed to analyze the indirect and cumulative impacts of the challenged Mancos Shale drilling permits on cultural sites in the Greater Chaco Landscape.” Aplts. Br. at 1 (footnote omitted). Second, they argue that the BLM violated NEPA because it “failed to analyze the cumulative impacts of the challenged Mancos Shale drilling permits on environmental resources in the Greater Chaco Landscape.” Id. at 2. Appellants seek vacatur of the challenged APDs and a permanent injunction against “any further ground-disturbing activities on the challenged APDs until BLM complies with the NHPA and NEPA.” Id. at 51.

Federal Appellees assert, as they did in the district court, that Appellants lack standing to challenge the relevant agency actions.

II

NEPA is also a procedural statute. It requires agencies to “pause before committing resources to a project and consider the likely environmental impacts of the preferred course of action as well as reasonable alternatives.” N.M. ex rel. Richardson v. Bureau of Land Mgmt., 565 F.3d 683, 703 (10th Cir. 2009). NEPA has twin aims:

First, it places upon an agency the obligation to consider every significant aspect of the environmental impact of a proposed action. Second, it ensures that the agency will inform the public that it has indeed considered environmental concerns in its decisionmaking process.

Forest Guardians v. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Serv., 611 F.3d 692, 711 (10th Cir. 2010) (quoting Balt. Gas & Elec. Co. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 462 U.S. 87, 97, 103 S.Ct. 2246, 76 L.Ed.2d 437 (1983)).

Neither NEPA nor NHPA “provide a private right of action,” so we review the two decisions as “final agency action[s] under the” APA. Utah Envtl. Cong. v. Russell, 518 F.3d 817, 823 (10th Cir. 2008). We apply the same standard of review as the district court: the familiar “arbitrary and capricious” standard. Richardson, 565 F.3d at 704–05; 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(A). An agency’s decision is arbitrary and capricious if the agency:

(1) entirely failed to consider an important aspect of the problem, (2) offered an explanation for its decision that runs counter to the evidence before the agency, or is so implausible that it could not be ascribed to a difference in view or the product of agency expertise, (3) failed to base its decision on consideration of the relevant factors, or (4) made a clear error of judgment.

Richardson, 565 F.3d at 704 (citations and quotations omitted). “A presumption of validity attaches to the agency action and the burden of proof rests with [the parties] who challenge such action.” Citizens’ Comm. to Save Our Canyons v. Krueger, 513 F.3d 1169, 1176 (10th Cir. 2008) (quoting Colo. Health Care Ass’n v. Colo. Dep’t of Soc. Servs., 842 F.2d 1158, 1164 (10th Cir. 1988)). Our deference to the agency is “especially strong where the challenged decisions involve technical or scientific matters within the agency’s area of expertise.” Morris v. U.S. Nuclear Reg. Comm’n, 598 F.3d 677, 691 (10th Cir. 2010) (quoting Russell, 518 F.3d at 824).

III

When, as here, an organization sues on behalf of its members, the organization has standing if:

(a) its members would otherwise have standing to sue in their own right; (b) the interests it seeks to protect are germane to the organization’s purpose; and (c) neither the claim asserted nor the relief requested requires the participation of individual members in the lawsuit.

Hunt v. Wash. State Apple Advert. Comm’n, 432 U.S. 333, 343, 97 S.Ct. 2434, 53 L.Ed.2d 383 (1977). Federal Appelles do not argue that the interests Appellants seek to protect are not germane to the organizations’ purposes, nor do they argue that the participation of individual members is required.3 Our standing inquiry is therefore limited to whether any of Appellants’ members “have standing to sue in their own right.” Id. We conclude that they do.

To establish standing, a plaintiff must show:

(1) it has suffered an “injury in fact” that is (a) concrete and particularized and (b) actual or imminent, not conjectural or hypothetical; (2) the injury is fairly traceable to the challenged action of the defendant; and (3) it is likely, as opposed to merely speculative, that the injury will be redressed by a favorable decision.

Friends of the Earth v. Laidlaw Envtl. Servs. (TOC), Inc., 528 U.S. 167, 180–81, 120 S.Ct. 693, 145 L.Ed.2d 610 (2000). At the summary judgment stage, Appellants must “set forth by affidavit or other evidence specific facts, which for purposes of the summary judgment motion will be taken to be true.” Lujan v. Defs. of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 561, 112 S.Ct. 2130, 119 L.Ed.2d 351 (1992) (citations and quotations omitted).

A

The injury-in-fact prong of our standing analysis “breaks down into two parts.” Comm. to Save the Rio Hondo v. Lucero, 102 F.3d 445, 449 (10th Cir. 1996). Appellants must show that (1) “in making its decision without following [NEPA’s] procedures, the agency created an increased risk of actual, threatened, or imminent environmental harm,” and (2) “the increased risk of environmental harm injures [the litigant’s] concrete interests by demonstrating either its geographical nexus to, or actual use of the site of the agency action.” Id. Appellants have satisfied both requirements.

1

Under NEPA, “an injury of alleged increased environmental risks due to an agency’s uninformed decisionmaking may be the foundation for injury in fact under Article III.” Id. Here, the allegedly uninformed decisions Appellants challenge are the BLM’s approval of hundreds of APDs in the Mancos Shale without considering the indirect and cumulative impacts to cultural sites and environmental resources. Aplts. Br. at 1–2. Appellants have sufficiently tied the BLM’s challenged decisions to increased environmental risks.

Eisenfeld, a member of San Juan Citizens and WildEarth, asserts that the “Mancos Shale APD authorizations ... impact[ ] the visual landscape, night sky, solitude and quiet, [and] public health and safety.” JA343. Nichols, a member of WildEarth, states that “[w]ith the increase in oil and gas development has come light pollution, more truck traffic, drilling rigs sticking up from the land, smells, dust, and more industrialization.” JA615. He asserts that recently,

the impacts of Mancos shale oil development have become more visible, offensive, and degrading of [his] recreational enjoyment of public lands in the area. The new development has brought more drilling rigs, flaring, truck traffic, road building, pipeline construction, the construction and operation of more tanks and production facilities, and just overall more oil and gas industry presence in the area.

JA607–08. These facts are sufficient to establish “an increased risk of environmental harm due to [the BLM’s] alleged uninformed decisionmaking,” and they satisfy the first prong of our injury-in-fact analysis. Lucero, 102 F.3d at 451.

Federal Appellees argue that Appellants fail on this prong of the standing analysis because the 2003 EIS examined the effects of “drilling 9,942 wells using conventional techniques,” and Appellants have not shown that the challenged Mancos Shale APDs “will increase the risk of environmental harm in a manner or to a degree not already considered.” Fed. Aples. Br. at 26. This argument conflates the standing analysis with the merits analysis.

As discussed, Appellants have submitted affidavits that show an increase in environmental harm from drilling activities in the Mancos Shale area; this satisfies the first prong of our injury-in-fact analysis. Whether that environmental harm is of a manner or to a degree not already considered in the 2003 EIS is a question that goes to the merits of Appellants’ NEPA claim. Appellants, of course, need not prove the merits of their claim in order to establish standing. See, e.g., Steel Co. v. Citizens for a Better Env’t, 523 U.S. 83, 89, 118 S.Ct. 1003, 140 L.Ed.2d 210 (“It is firmly established in our cases that the absence of a valid (as opposed to arguable) cause of action does not implicate subject-matter jurisdiction....”).

2

Standing “also requires a plaintiff be among the injured.” Lucero, 102 F.3d at 449. Therefore, Appellants “must be able to show that a separate injury to [their] concrete, particularized interests flows from the agency’s procedural failure.” Id. (citing Lujan, 504 U.S. at 572, 112 S.Ct. 2130). To demonstrate harm to a plaintiff’s concrete interests, the plaintiff must “establish either its geographic nexus to, or actual use of the site where the agency will take or has taken action such that it may be expected to suffer the environmental consequences of the [challenged] action.” Id. (quotations omitted).

Appellants’ members’ affidavits show a geographic nexus to the affected areas sufficient to satisfy the second prong of our injury-in-fact analysis. Eisenfeld states that he “regularly visit[s] the greater Chaco region, including areas in and around Counselor, Lybrook, and Nageezi,” and that he “intend[s] to go back [to Nageezi] in May and June of 2017.”4 JA338. He also states that he has “visited hundreds of well sites in the [Greater Chaco] area, and ha[s] frequented lands where many other Mancos Shale wells are in view.” JA342.

Nichols regularly visits the Greater Chaco region “for recreational enjoyment.” JA348. He describes visiting Pueblo Pintado, Chaco Culture National Historical Park (Chaco Park), Nageezi, and Pueblo Alto. Nichols “intend[s] to continue visiting the Greater Chaco region, including [Chaco Park] and its outliers, as well as public lands in the region, at least once a year for the foreseeable future,” and had a trip planned for “late June 2017.” JA351.

Kendra Pinto, a member of Diné, lives in Twin Pines, New Mexico, which is “located along Highway 550, at the county line of San Juan and Rio Arriba.” JA617. Beginning in 2013, she noticed a “major increase in Halliburton trucks along 550, and at the intersection of 7900 and 7950, trucks are staging right off the highway and even on the county road blocking traffic.” JA618. She “pass[es] through areas that are very potent in natural gas odors,” and has “seen the giant pillars of fire for the flaring the sites do.” JA619. She states that “[t]he lights staged at well sites can be as bright as stadium lights.” Id.

Deborah Green, a member of NRDC, visits the Chaco Canyon area and Chaco Park at least once a year. She states that “[o]il and gas leasing and development in the Chaco Canyon area/region and [Chaco Park] adversely affect[ ] the quality of [her] visitor experience in the area, and if expanded, would do so even more.” JA630. Along Highway 550, on the way to Chaco Park, Green has experienced

air pollution from gas flares at wells and large amounts of exhaust from the oil and gas company trucks and heavy equipment; noise pollution from heavy truck traffic; and light pollution when drilling goes on around the clock and from gas flares, which are visible from the road for a long distance at night.

Id.

These affidavits establish that the BLM’s challenged actions impair these individuals’ actual, concrete interests because the affiants have a geographical nexus to and actually use the land in the allegedly affected area.

Federal Appellees argue that the affidavits are insufficient for two reasons. First, they contend that Appellants have “challenged 337 individual agency actions,” each of which “gives rise to a distinct claim,” and that Appellants “must establish standing ... for each challenged APD approval.” Fed. Aples. Br. at 23. Second, they argue that Appellants “fail to establish a geographical nexus to the challenged agency actions” because Appellants’ affidavits all refer generally to the “greater Chaco region” or the “Mancos Shale formation.” Id. at 26–27. Both arguments fail.

As Appellants point out, we have previously rejected similar arguments. In Palma, the district court held that the plaintiffs did not establish an injury in fact because they submitted affidavits that “did not identify specific visits to each of the thirty-nine leases at issue.” 707 F.3d at 1155. This holding, we concluded, misapplied the law. Id. “Neither our court nor the Supreme Court has ever required an environmental plaintiff to show that it has traversed each bit of land that will be affected by a challenged agency action.” Id. Rather, “[a] plaintiff who has repeatedly visited a particular site, has imminent plans to do so again, and whose interest are harmed by a defendant’s conduct has suffered injury in fact that is concrete and particularized.” Id. at 1156. In Palma, an organization’s member’s affidavit was “sufficient” when “[h]e specified areas which he has visited, averred that these specific areas will be affected by oil and gas drilling, and stated his interests will be harmed by such activity.” Id. The affidavits Appellants submitted in this case meet this standard.5

Further, maps in the record indicate the geographic proximity of challenged APD sites to specific areas referenced in Appellants’ affidavits. Nichols attached to his declaration a map of the area around Chaco Park that shows the proximity of existing and new wells to Chaco Park and other locations affiants describe. This and other maps in the record indicate that challenged well sites are within twenty miles or less of Chaco Park, where Nichols and Green recreate; along Highway 550, the road to enter Chaco Park; and within several miles of Twin Pines, where Pinto lives, and Nageezi, where Eisenfeld and Nichols both recreate.

Furthermore, Appellants in this case challenge the BLM’s alleged failure to evaluate the indirect and cumulative impacts of the APDs, not merely the direct impacts of drilling to the area immediately surrounding the wellpads. Although Appellants’ NEPA claim is in the form of challenges to numerous individual APDs, the allegedly affected area extends beyond the boundaries of the well sites and into the greater Chaco landscape. Affiants’ descriptions of environmental harms including “air pollution from gas flares at wells,” “exhaust from the oil and gas company trucks and heavy equipment,” “noise pollution from heavy truck traffic,” and “light pollution” from drilling and “gas flares,” JA630, which they experience as they live and recreate in the affected area, are sufficient to place Appellants “among the injured.” Lucero, 102 F.3d at 449.

Appellants have shown through their members’ affidavits that some of their members have a geographical nexus to, and actually use, land the BLM has exposed to an increased risk of environmental harm due to its alleged uninformed decisionmaking. Appellants have established an injury in fact for purposes of Article III.

B

To establish causation, an environmental plaintiff “need only trace the risk of harm to the agency’s alleged failure to follow [NEPA]’s procedures.” Lucero, 102 F.3d at 452. A NEPA injury “results not from the agency’s decision, but from the agency’s uninformed decisionmaking.” Id. (first emphasis added).

Federal Appellees argue that Appellants have not shown that “the relief sought—the vacatur of BLM’s decisions approving these 337 APDs—will remedy their alleged injuries.” Fed. Aples. Br. at 29. They assert that Appellants have not established that their environmental harms were caused by “the 337 challenged permits rather than ... the approximately 23,000 active oil and gas wells in the San Juan Basin that are not the subject of this action.” Id. This argument fails.

“In the context of a [NEPA] claim, the injury is the increased risk of environmental harm to concrete interests....” Lucero, 102 F.3d at 451 (emphasis added). In this case, Appellants’ asserted injury is the increased risk of environmental harm from the additional wells, and it is undisputed that BLM has authorized more than 300 additional wells in the Mancos Shale. Appellants have alleged that the BLM did not comply with NEPA in granting the challenged APDs, and that its alleged failure resulted in “the agency’s uninformed decisionmaking” as to these additional wells. Id. at 452. This is sufficient to establish causation.

C

Appellants must also establish that it is “likely, as opposed to merely speculative, that the injury will be redressed by a favorable decision.” Lujan, 504 U.S. at 561, 112 S.Ct. 2130 (quotations omitted). Under NEPA, “a plaintiff need not establish that the ultimate agency decision would change upon [NEPA] compliance. Rather, the [Plaintiff must only show] that its injury would be redressed by a favorable decision requiring” compliance with NEPA procedures. Lucero, 102 F.3d at 452 (quotations and citations omitted). Here, Appellants challenge the BLM’s decision to grant APDs without conducting the requisite NEPA analysis. A favorable decision ordering compliance with NEPA’s procedures would “avert the possibility that the [BLM] may have overlooked significant environmental consequences of its actions,” thereby redressing Appellants’ alleged harms. Id. Appellants have established redressability.

Because individual members of Appellants’ organizations have suffered a concrete and particularized injury in fact that is fairly traceable to the BLM’s alleged failure to comply with NEPA and could be redressed by a favorable decision, we conclude that Appellants have standing.6

IV

As to NHPA, the record indicates that the BLM considered impacts on historic properties in at least three documents for each APD: (1) a Cultural Resource Survey (CRS), (2) a Record of Review, and (3) a site-specific EA. Therefore, in order to evaluate the sufficiency of the BLM’s NHPA analysis, we would need the complete EA, complete CRS, and complete Record of Review for each challenged APD. The record, however, contains portions of the BLM’s NHPA analysis for only seventeen different sets of APDs.7 Further, the vast majority of the NHPA analyses in the record are only several-page excerpts, not the entire analysis. The record contains the complete EA, CRS, and Record of Review for only one set of challenged APDs: Kimbeto Wash Unit Wells 787H, 789H, and 791H.

As to NEPA, the record indicates that the BLM’s NEPA analysis was included in at least each site-specific EA and the 2003 EIS (to which each of the site-specific EAs tiered). Therefore, in order to evaluate the sufficiency of the BLM’s NEPA analyses, we would need the complete 2003 EIS and the complete EA for each challenged APD. The record, however, only includes portions of twenty-seven EAs. And, as with the NHPA analyses, the vast majority of the EAs in the record are several-page excerpts, not the complete EA. From our count, the record contains only six complete EAs: EA 2012-0268, EA 2014-0272, EA 2015-0036, EA 2015-0066, EA 2016-0029, and EA 2016-0200/2016-0076. We are therefore able to analyze whether the BLM violated NEPA only as to those six EAs.

“[O]ur cases addressing deficiencies in the appendix submitted by an appellant define a guiding principle....” Lincoln v. BNSF Ry. Co., 900 F.3d 1166, 1190 (10th Cir. 2018). Even when an appendix is deficient, if “the materials provided by the appellant permit us to reach a firm and definite conclusion regarding the merits of an individual argument or claim within the appeal,” we often will address the argument or claim, although our rules do not require us to do so. Id. But if “we are forced to venture a guess as to the merits of an argument or claim, even ‘an informed guess,’ we will summarily affirm the district court’s judgment.” Id. (collecting cases).

Applying these principles, we conduct our NHPA and NEPA reviews only as to those challenged actions for which we have the BLM’s complete analysis. For NHPA, we evaluate the sufficiency of the BLM’s analysis for Kimbeto Wash Unit Wells 787H, 789H, and 791H. For NEPA, we evaluate the sufficiency of the BLM’s analysis for: (1) EA 2012-0268, (2) EA 2014-0272, (3) EA 2015-0036, (4) EA 2015-0066, (5) EA 2016-0029, and (6) EA 2016-0200/2016-0076.8 As to all other challenged agency actions, the record “is insufficient to permit assessment of [Appellants’] claim of error,” and we affirm the district court. Tilton v. Capital Cities/ABC, Inc., 115 F.3d 1471, 1474 (10th Cir. 1997).

V

A

Section 106 of NHPA sets forth specific processes federal agencies must perform to comply with NHPA. See 36 C.F.R. § 800.1(a). In general, the Section 106 process involves four steps. First, the agency defines the APE. 36 C.F.R. § 800.4(a). The APE is “the geographic area or areas within which an undertaking may directly or indirectly cause alterations in the character or use of historic properties, if any such properties exist.” Id. § 800.16(d). “Establishing an [APE] requires a high level of agency expertise, and as such, the agency’s determination is due a substantial amount of discretion.” Valley Cmty. Pres. Comm’n v. Mineta, 373 F.3d 1078, 1092 (10th Cir. 2004).

After defining the APE, the agency identifies historic properties within the APE. 36 C.F.R. § 800.4(b). A historic property is “any prehistoric or historic district, site, building, structure, or object included on, or eligible for inclusion on” the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). 54 U.S.C. § 300308. If the agency determines that no historic properties are present within the APE, it reports that finding and the NHPA process ends. 36 C.F.R. § 800.4(d)(1).

If historic properties are present within the APE, the agency determines whether the proposed undertaking will adversely affect those properties. Id. § 800.5. An adverse effect exists “when an undertaking may alter, directly or indirectly, any of the characteristics of a historic property that qualify the property for inclusion in the [NRHP] in a manner that would diminish the integrity of the property’s location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, or association.” Id. § 800.5(a)(1). Adverse effects include “reasonably foreseeable effects caused by the undertaking that may occur later in time, be farther removed in distance or be cumulative.” Id. They also include the “[i]ntroduction of visual, atmospheric[,] or audible elements that diminish the integrity of the property’s significant historic features.” Id. § 800.5(a)(2)(v).

If the agency determines that the undertaking may cause an adverse effect on the historic properties within the APE, it must “develop and evaluate alternatives or modifications to the undertaking that could avoid, minimize, or mitigate adverse effects on historic properties.” Id. § 800.6(a). The Section 106 process does not demand a particular result, however, because “Section 106 is essentially a procedural statute and does not impose a substantive mandate” on the agencies governed by it. Valley Cmty., 373 F.3d at 1085.

Section 106 authorizes agencies to enter into a “programmatic agreement to govern the implementation of a particular program or the resolution of adverse effects from certain complex project situations or multiple undertakings.” 36 C.F.R. § 800.14(b). When a governing programmatic agreement is in place, compliance with the procedures in that agreement satisfies the agency’s NHPA Section 106 responsibilities for all covered undertakings. Id. § 800.14(b)(2)(iii).

The parties agree that two programmatic agreements governed the BLM’s NHPA analyses of the APDs in this case: one agreement that went into effect in 2004 (the 2004 Protocol), and one that went into effect in 2014 (the 2014 Protocol). Therefore, we must resolve whether Appellants have shown that the BLM violated the requirements of the 2014 Protocol9 as to the single challenged APD properly before us. Although the compliance requirements for the 2014 Protocol are somewhat different than Section 106’s requirements, the basic NHPA process is the same.

The 2014 Protocol states generally that, “[i]n defining the APE, the BLM will consider potential direct, indirect, and cumulative effects to historic properties and their associated settings when setting is an important aspect of integrity, as applicable.” JA1562. Relevant here, the 2014 Protocol states that “[t]he BLM will follow the established guidance on standard direct APEs for certain types of projects in Appendix B.” Id. (italics omitted). Appendix B sets a “standard APE” for well pads of “the well pad and construction zone plus 100[ ] [feet] on each side from the edge of the construction zone.” JA1594. The 2014 Protocol acknowledges that “[i]n certain circumstances, even though an undertaking may have a standard APE ..., the Field Manager, at the recommendation of the cultural resource specialist, may have justification to require a larger APE.” Id.

B

Appellants argue that the BLM “failed to account for indirect impacts to cultural sites, as required by the NHPA and the Protocol.” Aplts. Br. at 30. According to Appellants, “the Protocol requires BLM to consider a separate APE for indirect effects where ‘[t]he introduction of physical, visual, or audible elements has the potential to affect the historic setting or use’ of cultural sites ‘where setting is an important aspect of integrity.’ ” Id. at 31 (quoting JA1562). Appellants’ argument fails because the 2014 Protocol merely allows for, it does not require, a separate indirect-effects APE.

The 2014 Protocol acknowledges that “[t]he introduction of physical, visual, audible, or atmospheric elements has the potential to affect the historic setting or use of historic properties,” and requires the BLM to “take this into account in defining the limits of an APE for indirect effects.” JA1562 (emphasis added). Under the 2014 Protocol, “[t]he indirect APE shall include known or suspected historic properties and their associated settings where setting is an important aspect of integrity.” Id. The 2014 Protocol continues: “Identification efforts outside of the APE for direct effects shall be at the approval of the BLM field manager, taking into account the recommendations of the BLM cultural resource specialist and the SHPO.” Id. (emphasis added). In other words, the BLM need not set—or even consider—a separate indirect-effects APE when “physical, visual, audible, or atmospheric elements ha[ve] the potential to affect the historic setting or use of historic properties,” as Appellants argue. JA1562. Rather, the 2014 Protocol only requires that the BLM take indirect effects into account as it exercises its substantial discretion in setting the APE. The 2014 Protocol therefore contains a default presumption that the direct and indirect APE will be the same and, to the extent the BLM will attempt to identify historic properties outside the direct-effects APE, those identification efforts will be at the approval of the BLM field manager.

Moreover, the CRS, the Record of Review, and the EA for the Kimbeto Wash Unit wells indicate that the BLM looked to areas far outside the standard direct-effects APE to identify cultural properties. The EA includes a fulsome discussion of the potential for indirect impacts from the proposed project, including an analysis of visual resources. The EA notes that the proposed action is at least 8.5 miles “from the boundary of [Chaco Park].” Id. It acknowledges that “small portions of the pipeline fall within” two National Park Service designated Key Observation Points, but concludes that “[g]iven [the] distance ( [over] 11.5 miles) and low profile[,] the pipeline will not be visible.” JA1949. The EA notes that the project’s “well pad is within a mile of a few scattered residences,” but concludes that it is “unlikely that the well pad will be visible from these residences due to area topography.” JA1950. It also states that the “well pad will not visible from any designated recreation areas.” Id.

The EA also addresses the project’s potential impact on night skies, noting that “[l]ight sources associated with drilling an oil and gas well include a light plant or generator, a light on top of the rig, vehicle traffic, and flaring.” JA1951.

The necessity for flaring and the duration of flaring varies widely from well to well and is difficult to predict. With the exception of a few yearly events, visitors are not allowed access to the canyon rim where the proposed action may be seen after sunset, minimizing the chance that visitors would see the direct light. While these lights could reduce the general darkness of the night sky as seen from [Chaco Park], it is likely the impact would be imperceptible.

Id. Further, the EA notes that any potential light impacts “would be short-term.” Id.

The CRS and Record of Review also indicate that the BLM looked for historic sites in an area that extended far beyond the direct-effects APE. The CRS notes that a record search was conducted and “[n]o sites listed on the State Register of Cultural Properties or the [NRHP we]re located within a 1 mile [sic] of the project area.” JA2173 (emphasis added). The BLM also conducted pedestrian surveys of a 108.01-acre area, although the CRS indicates only 25.76 acres in the APE. [Id.] During the pedestrian surveys, “[w]hen cultural material was encountered, it was pin flagged and the archaeologists began an intensive search of the area to locate other material.” JA2175. After eight “Fieldwork Dates,” forty-six “Survey Person Hours” and thirty-nine “Recording Person Hours,” the BLM’s NHPA review identified four newly recorded cultural sites, one previously recorded site, and twelve isolated occurrences of cultural material. Id. The BLM ultimately determined that three of the five sites were ineligible for listing on the NRHP, and two were eligible but avoided. The BLM therefore recommended that the project go forward with mitigation requirements, including employee education, temporary barriers, and archaeological site monitoring.

The CRS, Record of Review, and EA for the Kimbeto Wash Unit wells indicate that the BLM attempted to identify historic properties in an area far outside the standard direct-effects APE for well pads, and that the BLM considered the proposed drilling’s possible visual impacts, including its impact on night skies. Given this analysis, especially considering that it far exceeded the analysis required by the 2014 Protocol, Appellants have failed to establish that the BLM violated NHPA by not adequately considering the indirect effects of the Kimbeto Wash Unit wells.10

C

Appellants also argue that the BLM violated NHPA because it “failed to analyze the cumulative effects of developing hundreds of new APDs across this culturally significant landscape.” Aplts. Br. at 38. Appellants’ cumulative-effects argument fails because Appellants identify no historic properties within the APE the BLM set.

In support of their cumulative-effects argument, Appellants cite to 36 C.F.R. § 800.5(a)(1), which states that “[a]dverse effects may include reasonably foreseeable effects caused by the undertaking that may occur later in time, be farther removed in distance or be cumulative.” This regulation, however, addresses the BLM’s application of “the criteria of adverse effect to historic properties within the [APE].” 36 C.F.R. § 800.5(a) (emphasis added). In other words, the cited language simply means that an undertaking can have adverse effects on historical properties within the APE, even if the undertaking only adversely affects the properties through “reasonably foreseeable effects caused by the undertaking that may ... be cumulative.” Id. § 800.5(a)(1).

Appellants, however, argue that the BLM abused its discretion by failing to analyze the cumulative adverse effects horizontal Mancos Shale wells might have “on the integrity of the historic setting for any number of cultural sites, [Chaco] Park, and the Greater Chaco Landscape.” Aplts. Br. at 37. This argument ignores that § 800.5(a)(1) applies to the BLM’s assessment of adverse effects on “historic properties within the [APE].” 36 C.F.R. § 800.5(a) (emphasis added). And the record indicates that the APE for the Kimbeto Wash Unit wells did not encompass the “cultural sites, [Chaco] Park, and the Greater Chaco Landscape,” Aplts. Br. at 37, which Appellants argue would be negatively impacted by these cumulative effects.11

In sum, Appellants’ cumulative-effects argument is premised on an APE different from the one the BLM defined. Appellants’ argument therefore fails.

D

Appellants also argue that the BLM was required to consult with the SHPO12 because defining APEs for the challenged APDs was “complicated or controversial.” Aplts. Br. at 35. In support, Appellants cite the 2014 Protocol’s examples of “complicated or controversial” projects, contending that the APDs at issue qualify because “ ‘multiple applicants’ [and] ‘multiple Indian tribes’ are involved.” Id. (quoting JA1562). Appellants’ SHPO consultation argument fails.

The 2014 Protocol “specifies the manner in which the BLM works with SHPO,” and “establishes a streamlined consultation process for most BLM undertakings.” JA1552. It provides that “[t]he BLM will consult with SHPO on undertakings for which a standard APE ... has not been developed.” JA1562. Appendix B indicates that if the BLM utilizes a standard APE for an undertaking, the “BLM and SHPO have consulted” as to that APE. JA1594 (emphasis added). The 2014 Protocol also states that the BLM will consult with the SHPO “where the APE is complicated or controversial,” and gives examples of situations in which defining the APE may be complicated or controversial: “undertakings involving multiple agencies, multiple states, multiple applicants, and/or multiple Indian tribes.” JA1562.

The 2014 Protocol therefore establishes a default presumption that the BLM need not consult with the SHPO “on undertakings for which a standard APE” exists, such as the undertakings at issue in this case. JA1562. And in this case, the applicability of a standard APE also undermines a conclusion that the APE is complicated or controversial. Rather, the existence of a standard APE indicates that the BLM and the SHPO anticipated that the BLM would often have to define an APE for activities related to oil and gas drilling, such as well pads, pipelines, and roads. And, seeking to “streamline the consultation process” for these common undertakings, the BLM and the SHPO determined that a standard APE for these activities would suffice in most circumstances, and BLM-SHPO consultation in defining the specific APE would be unnecessary. JA1552; accord JA1562. We therefore reject Appellants’ argument that the BLM abused its discretion by not consulting with the SHPO.

Appellants fail to carry their burden of establishing that the BLM violated NHPA. The BLM’s decision is entitled to a presumption of regularity, and it finds support in the record. Accordingly, we affirm the district court’s dismissal of Appellants’ NHPA claim.

VI

A

NEPA “requires federal agencies ... to analyze environmental consequences before initiating actions that potentially affect the environment.” Utah Env’t Cong. v. Bosworth, 443 F.3d 732, 735–36 (10th Cir. 2006). To comply with NEPA, agencies must prepare a detailed statement of the environmental impact of any “major Federal action[ ] significantly affecting the quality of the human environment.” 42 U.S.C. § 4332(2)(C).

In conducting its NEPA analysis, a federal agency must prepare, as relevant here, either “(1) an environmental impact statement [ (EIS) ], [or] (2) an environmental assessment [ (EA) ].” Bosworth, 443 F.3d at 736. An EIS “is required if a proposed action will ‘significantly affect[ ] the quality of the human environment.’ ” Id. (alteration in original) (quoting 42 U.S.C. § 4332(C)). “If an agency is uncertain whether the proposed action will significantly affect the environment, it may prepare a considerably less detailed [EA].” Id.

Although less detailed than an EIS, the EA must still “include brief discussions of the need for the proposal, of alternatives ..., [and] of the environmental impacts of the proposed action and alternatives.” 40 C.F.R. § 1508.9(b). Among the environmental impacts the EA must evaluate are “the cumulative impacts of a project.” WildEarth Guardians v. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Serv., 784 F.3d 677, 690 (10th Cir. 2015) (quoting Davis v. Mineta, 302 F.3d 1104, 1125 (10th Cir. 2002) abrogated on other grounds by Diné Citizens Against Ruining Our Env’t v. Jewell, 839 F.3d 1276 (10th Cir. 2016)). Cumulative impacts are “the impact on the environment which results from the incremental impact of the action when added to other past, present, and reasonably foreseeable future actions.” 40 C.F.R. § 1508.7. Cumulative impacts can result from “individually minor but collectively significant actions taking place over a long period of time.” Id.

If, after considering the necessary factors, the agency concludes the action is unlikely to have a significant environmental impact, it may issue a finding of no significant impact (FONSI) and proceed with the action. 40 C.F.R. § 1508.13. If the agency reaches the opposite conclusion, before proceeding with the action, it must prepare an environmental impact statement to thoroughly analyze the action’s predicted environmental impacts, including its direct, indirect, and cumulative impacts. 42 U.S.C. § 4332(2)(C); 40 C.F.R. §§ 1508.11, 1508.25. However, even when a proposed action has “significant effects,” the BLM may tier13 an EA to an existing EIS—and thereby reach a FONSI—if the EIS to which it tiers “fully analyzed those significant effects.” 43 C.F.R. § 46.140(c). But if the “relevant analysis in the [EIS] is not sufficiently comprehensive or adequate to support further decisions, the [EA] must explain this and provide any necessary analysis.” Id. § 46.140(b).

“The role of a federal court under NEPA is to review the EIS, [or] EA, ... as the case may be, and ‘simply ... ensure that the agency has adequately considered and disclosed the environmental impact of its actions.’ ” Concerned Citizens, 843 F.3d at 902 (third alteration in original) (quoting Wyoming v. U.S. Dep’t of Agric., 661 F.3d 1209, 1256–57 (10th Cir. 2011)). In conducting this review, we apply a “rule of reason standard” to determine whether claimed NEPA violations “are merely flyspecks, or are significant enough to defeat the goals of informed decision making and informed public comment.” Utahns for Better Transp. v. U.S. Dep’t of Transp., 305 F.3d 1152, 1163 (10th Cir. 2002).

B

Appellants first argue that the challenged APDs cause environmental impacts qualitatively different from those considered in the 2003 EIS because the APDs authorize drilling in the southern portion of the Mancos Shale, while the 2003 EIS “only evaluated development in the northern portion.” Aplts. Br. at 42. Appellants’ argument fails because the 2003 EIS evaluated the effects of drilling throughout the entire San Juan Basin—an area that includes the location of the challenged APDs.

The 2003 EIS was developed to “analyze[ ] the environmental impacts of oil and gas leasing and development in the San Juan Basin in New Mexico.” JA767. The “planning area” addressed in the 2003 EIS “includes all of San Juan County, most of McKinley County, western Rio Arriba County, and northwestern Sandoval County.” JA768. All challenged APDs are within this area.

The 2003 EIS denoted the northeastern portion of the planning area as a “high development area” for oil and gas production, but that area was so identified because “more than 99 percent of the federal oil and gas resources [we]re currently leased” in that area. JA778. Nothing in the 2003 EIS indicates that the BLM analyzed the environmental impacts of drilling on only the high development area. Indeed, the 2003 EIS’s chapter on the affected environment contains a lengthy discussion of the cultural resources present in the Chaco Canyon. The record, therefore, does not support Appellants’ assertion that the challenged APDs are in a geographic area not considered by the 2003 EIS.

C

Appellants also argue that the BLM has never fully analyzed the cumulative environmental impacts of drilling 3,960 horizontal wells in the Mancos Shale because those impacts exceed the environmental impacts evaluated in the 2003 EIS in two specific ways: air pollution and water use. As to air pollution, we conclude that Appellants have not provided us with a record from which we can assess the BLM’s NEPA analysis. As to water use, we conclude that Appellants have shown that the BLM never considered the cumulative impact of the water use associated with the 3,960 reasonably foreseeable horizontal Mancos Shale wells for five specific EAs. We therefore reverse the district court’s dismissal of Appellants’ NEPA claims as to EAs 2014-0272, 2015-0036, 2015-0066, 2016-0029, and 2016-0200/2016-0076.14

1

Appellants’ cumulative-impacts argument relies on one assumption the parties dispute: that the BLM’s NEPA analysis must consider the impacts associated with all 3,960 wells the 2014 RFDS identified as possible if full-field Mancos Shale development occurs. We conclude that the 2014 RFDS made it reasonably foreseeable that 3,960 horizontal Mancos Shale wells would be drilled, and NEPA therefore required the BLM to consider the cumulative impacts of those wells in the EAs it conducted for subsequent horizontal Mancos Shale well APDs.

The 2014 RFDS “collect[ed] and analyze[d] geological and engineering evidence[ ] ... to determine the potential subsurface development of the Gallup/Mancos play.” JA1665. Based on this analysis, it estimated that full development of the Mancos Shale would result in 3,960 new wells. And, although it predicted “a five[-]year delay in significant activity” in the Mancos Shale area “due to unfavorable economics,” it also predicted that well activity would “rapidly increase” once the economics became more favorable. JA1662.

The BLM itself has relied on RFDSs to define the scope of “reasonably foreseeable” actions for the purposes of its cumulative-impacts analyses. For example, two of the EAs before us cite to the 2014 RFDS in their discussions of cumulative impacts. In describing the methodology used to analyze cumulative impacts, EA 2016-0029 and EA 2016-0200/2016-0076 discuss oil and gas development predicted in the 2014 RFDS, noting that the 2014 RFDS

identified high, moderate, and low potential regions for oil development of the Mancos-Gallup Formation. Within the high potential region, full development would include 5 wells per section, resulting in 1,600 completions. Within the moderate potential region, full development would include one well per section, resulting in 330 completions. Within the low potential region, full development would include one well per township, resulting in 30 well completions. Additionally, the [2014 RFDS] predicted 2,000 gas wells could be development [sic] in the northeastern corner of the [BLM’s Farmington Field Office].

JA1926; JA2096. The BLM also relied on the 2001 RFDS for projected drilling amounts in the 2003 EIS. The 2003 EIS states that the 2001 RFDS “form[ed] the basis for projected oil and gas development in the planning area over the next 20 years.” JA769–70. Especially in light of the BLM’s past reliance on the drilling projected in RFDSs, we conclude that once the 2014 RFDS issued, the 3,960 horizontal Mancos Shale wells predicted in that document were “reasonably foreseeable future actions.” 40 C.F.R. § 1508.7; accord Sierra Club v. Marsh, 976 F.2d 763, 767 (1st Cir. 1992) (“[A]s in other legal contexts, the terms ‘likely’ and ‘foreseeable,’ as applied to a type of environmental impact, are properly interpreted as meaning that the impact is sufficiently likely to occur that a person of ordinary prudence would take it into account in reaching a decision.”). The BLM therefore needed to consider the cumulative environmental impacts associated with the reasonably foreseeable 3,960 horizontal Mancos Shale wells when it conducted EAs for the challenged APDs.

Intervenor Appellees’ arguments do not persuade us otherwise. First, we of course acknowledge that “full-field [Mancos Shale] development is not at issue in this case.” Int. Aples. Br. at 38. But that does not excuse the BLM from NEPA’s requirement that it “take a ‘hard look’ at the environmental consequences before” approving the challenged APDs. Balt. Gas & Elec. Co., 462 U.S. at 97, 103 S.Ct. 2246. And, in this case, that involved considering the cumulative impacts of the 3,960 reasonably foreseeable horizontal Mancos Shale wells. See 40 C.F.R. §§ 1508.9(b), 1508.7.

Second, we reject Intervenor Appellees’ argument that the BLM did not need to consider the cumulative impact of the predicted 3,960 wells because “no operator has proposed to drill” all of those wells. Int. Aples. Br. at 40. Once the 2014 RFDS issued, it became reasonably foreseeable to the BLM that the projected wells would be drilled, so the BLM needed to consider the cumulative impact of all those wells, even if the wells were not going to be drilled imminently. 40 C.F.R. § 1508.7 (“Cumulative impacts can result from individually minor but collectively significant actions taking place over a period of time.” (emphasis added)).

Finally, we reject Intervenor Appellees’ argument that our conclusion here would “automatically foreclose authorization of all individual activities in the [planning] area” once the BLM initiates an RMP amendment process. Int. Aples. Br. at 42. Rather, our decision forecloses only those activities with environmental impacts—direct, indirect, or cumulative—that have not been considered in either a site-specific EA or a broader NEPA document to which the EA tiers. But that is the purpose of NEPA: to “require[ ] federal agencies ... to analyze environmental consequences before initiating actions that potentially affect the environment.” Bosworth, 443 F.3d at 735–36.

We conclude that the 3,960 horizontal Mancos Shale wells predicted in the 2014 RFDS were reasonably foreseeable after the 2014 RFDS issued. The BLM therefore had to consider the cumulative impacts of all 3,960 wells when it conducted its site-specific EAs.

2

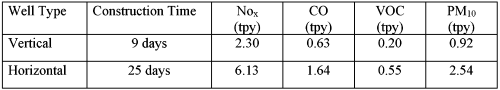

Appellants argue that the air pollution caused by the horizontal Mancos Shale wells will exceed the air pollution amounts considered in the 2003 EIS. In support, Appellants point to a table that purports to “illustrate the total combined impacts of past, present, and reasonably foreseeable future development.” Aplts. Br. at 43. Although the numbers in Appellants’ table indicate that horizontal wells have a much greater environmental impact than do vertical wells, the numbers Appellants provide for the environmental impacts of vertical wells are not supported by the record. More importantly, the record does not contain the BLM’s complete air pollution analysis, so we are unable to fully evaluate the air pollution argument Appellants make.

Appellants’ air pollution argument relies on the following assumptions:15

Id. at 44. Although these numbers support the conclusion that horizontal wells have a greater environmental impact than do vertical wells, these numbers are not supported either by the part of the record to which Appellants cite or by any other part of the record we could identify.

First, Appellants cite to “JA2331–32 ( [pages 4-61–4-62 of the] 2003 EIS providing qualitative assessment of air quality impairment and violations of air standards)” and “JA2328–29 (emissions estimates based on developing 663 wells per year)” in support of the numbers they list for air pollution associated with vertical wells. Aplts. Br. at 44 n.22. The first cited portion of the 2003 EIS, however, analyzes the overall potential effect of contemplated drilling operations on air quality in the project area. Those pages do not analyze the air pollution contemplated by construction of vertical wells, as Appellants indicate they do. Moreover, there is no discernible connection between any of the numbers in this cited portion of the 2003 EIS and the numbers in Appellants’ chart.

The same is true of the other portion of the record Appellants cite: JA2328–29 (pages 4-58 and 4-59 of the 2003 EIS). That portion of the 2003 EIS provides an “estimation of emissions for each year” under Alternative B.16 JA2328. A table on the second cited page contains categories that match the categories in Appellants’ chart—VOC, CO, Nox, and PM10. However, the table indicates that it depicts “Project Year 1 and Project Year 20 Annual Air Emissions Associated with Gas Production” under Alternative B. JA2329 (emphasis added). The numbers, therefore, do not represent air pollution associated with vertical well construction. And, once again, there is no discernible connection between any air pollution numbers in these pages and the vertical-well numbers in Appellants’ table.

Finally, Appellants indicate that the well construction time for a vertical well is nine days. Again, nothing in the part of the record to which Appellants cite supports that assertion. However, the 2003 EIS notes elsewhere that “the time to complete individual wells is generally between one and two months.” JA2287 (emphasis added). This indicates that Appellants’ cited nine days is incorrect.

More fundamentally, the record does not contain crucial aspects of the BLM’s NEPA analysis. Specifically, the record does not include the BLM’s complete air pollution analysis. The 2003 EIS notes that “Appendix J includes the emissions estimates for Alternative D.” JA2378. Appendix J also “presents data used to estimate annual air emissions” for each alternative. JA834. But Appendix J is not in the record.

Further, from our review, no other part of the record includes data that would facilitate the comparison on which Appellants rely: the gross amount of NOx, CO, VOC, and PM10 created in the construction of a single vertical well. Those numbers might be in Appendix J—and they might even be the numbers Appellants include in their chart—but we have no way of determining that because Appendix J is not in the record. We therefore cannot evaluate whether, as Appellants argue, “the 3,945 existing vertically drilled and the reasonably foreseeable 3,960 horizontally drilled Mancos Shale wells exceed the total impacts predicted in the 2003 EIS.” Aplts. Br. at 45.

Appellants do not include the BLM’s complete analysis of air pollution in the 2003 EIS, and therefore offer no way to compare the impacts contemplated by the 2003 EIS with the impacts that could result from 3,960 horizontal Mancos Shale wells. The BLM’s NEPA analysis “is entitled to the presumption of regularity,” Stiles, 654 F.3d at 1045, and Appellants have not carried their burden of demonstrating that the BLM acted arbitrarily or capriciously.

3

Appellants also argue that the total water used for drilling 3,960 horizontal Mancos Shale wells will exceed the water use contemplated in the 2003 EIS, and the BLM therefore abused its discretion in tiering the EAs to the 2003 EIS, issuing FONSIs, and approving APDs. We agree with Appellants that, as to five challenged EAs, the BLM did not consider the cumulative water use associated with the 3,960 reasonably foreseeable horizontal Mancos Shale wells. Therefore, as to these five EAs, the BLM’s issuance of FONSIs and approval of APDs was arbitrary and capricious.

Appellants’ water-resources argument, like their air-pollution argument, is based largely on calculations in their comparison table. First, Appellants state that drilling a single horizontal well will use 1,020,000 gallons of water. In contrast, Appellants assert the 2003 EIS predicted that drilling a single vertical well would use 283,500 gallons of water. Appellants then multiply each of these numbers by the total number of wells (3,960 reasonably foreseeable horizontal wells; 3,945 already drilled vertical wells) and arrive at a total water consumption amount of over 5 billion gallons of water. According to Appellants, the 2003 EIS contemplated total water use of just over 2.8 billion gallons. Therefore, argue Appellants, when the 3,960 reasonably foreseeable horizontal Mancos Shale wells are taken into account, the projected water use increases by 82% over what the 2003 EIS considered.

Although we note some discrepancies between Appellants’ cited numbers and the numbers in the record,17 we reject Federal Appellees’ argument that Appellants’ water-resources calculations “do not withstand scrutiny.” Fed. Aples. Br. at 33. Federal Appellees argue generally that water use could be decreased through “new strategies and technologies,” Fed. Aples. Br. at 35 (quotations omitted), but they do not point us to any part of the record that contradicts Appellants’ assertions that the cumulative water use associated with the reasonably foreseeable 3,960 wells dramatically exceeds the total water use contemplated in the 2003 EIS. We conclude that, regardless of the minor inaccuracies in their calculations, Appellants have established that the difference between the water use contemplated in the 2003 EIS and the water use associated with drilling the reasonably foreseeable horizontal Mancos Shale wells is more than a “mere[ ] flyspeck.” Utahns for Better Transp., 305 F.3d at 1163.

None of the five EAs before us considered the cumulative impacts of the water use associated with all 3,960 reasonably foreseeable horizontal Mancos Shale wells. The only discussion of water resources in EA 2015-0036 is as follows:

[T]he operator would follow ‘Pit Rule’ guidelines and Onshore Order No. 1. Drilling operations would utilize a closed-loop system. Drilling of the horizontal lateral would be accomplished with water-based mud. All cuttings would be hauled to a commercial disposal facility or land farm.

JA1241. Three other EAs (EA 2015-0066, EA 2016-0029, and EA 2016-0200/2016-0076) all list “Groundwater Resources” as an “issue considered but not analyzed.” JA1305; JA1911–12; JA2082–83. Each of these EAs discusses the general process for hydraulic fracturing, then concludes that “[n]o impacts to surface water or freshwater-bearing groundwater aquifers are expected to occur from hydraulic fracturing of these proposed wells.” JA1912; JA2083; accord JA1306 (containing the same substantive analysis with slightly different wording). EAs 2015-0036, 2015-0066, 2016-0029, and 2016-0200/2016-0076 contain no discussion of the cumulative impacts related to water resources.

EA 2014-0272 is the only EA that contains any discussion of the cumulative impacts on water resources. Its cumulative-impact analysis states:

Reasonably foreseeable development within the Largo sub-watershed may include an estimated additional 1,811 oil and gas wells and related facilities. Surface-disturbing activities that would be associated with these actions may affect an estimated 6,756 acres ( [2003 EIS], page 4-7). The [2003 EIS] determined that the primary cumulative impacts on water quality would result from surface disturbance, which would generate increased sediment yields ( [2003 EIS] pages 4-123 and 4-124). Cumulative effects to water resources from the proposed action would be maximized shortly after construction begins and would decrease over time as reclamation efforts progress.

The proposed action would cumulatively contribute approximately 20.0 acres of long-term disturbance in the watershed. Cumulative impacts to surface waters would be related to short-term sedimentation or flow changes. Surface-disturbing activities other than the proposed action that may cause accelerated erosion include—but are not limited to—construction of roads, other facilities, and installation of trenches for utilities; road maintenance such as grading or ditch cleaning; public recreational activities; vegetation manipulation and management activities; prescribed and natural fires; and livestock grazing.

JA1141. This analysis of the cumulative impacts on water resources does not address the water consumption associated with the 3,960 reasonably foreseeable Mancos Shale wells.

As to these five EAs, the BLM was required to, but did not, consider the cumulative impacts on water resources associated with drilling the 3,960 reasonably foreseeable horizontal Mancos Shale wells.18 The BLM therefore acted arbitrarily and capriciously in issuing FONSIs and approving APDs associated with these EAs.

Federal Appellees make two additional arguments in support of the BLM’s NEPA analysis, both of which we reject.

Federal Appellees first argue that Appellants advocate “too narrow a definition of cumulative impact—one that would require specific, quantitative measurements of all potential effects.” Fed. Aples. Br. at 33. Instead, argue Federal Appellees, the 2003 EIS analyzed cumulative impacts via a “broad, qualitative approach ... consistent with the purpose of [a] programmatic EIS.” Id. This argument fails because the record indicates that (1) the BLM did quantify the cumulative water-resources impacts of proposed drilling in the 2003 EIS, (2) the BLM could have quantified the cumulative water-resources impacts of the horizontal Mancos Shale wells, and (3) water use is an important aspect of the environmental impacts associated with well drilling.

First, the 2003 EIS quantified the total amount of water required for drilling operations in each considered alternative. Second, four of the five EAs we consider also included a quantitative measure of the amount of water the drilling operations for the proposed APDs would use. Finally, the 2003 EIS acknowledged that “[t]he primary issues and concerns regarding water resource problems caused by oil and gas development involve ... water consumption and use.” JA2283. Likewise, the 2014 RFDS noted that “[t]he development of the Mancos play will require additional fresh water for stimulation purposes,” and acknowledged that “horizontal completions ... require large volumes of water for hydraulic fracturing.” JA1686.

We therefore reject Federal Appellees’ argument that the BLM could conduct an adequate cumulative-impacts analysis without quantifying the amount of reasonably foreseeable water use. The BLM had non-speculative figures that it could use to quantify the cumulative impact of the drilling, and the water-resources impacts were important. The BLM was therefore required to consider those impacts to comply with NEPA. See Wyoming v. USDA, 661 F.3d at 1253 (rejecting the argument that an EIS failed to adequately consider cumulative impacts because “cumulative impacts that are too speculative or hypothetical to meaningfully contribute to NEPA’s goals of public disclosure and informed decisionmaking need not be considered”); Utah Envtl. Congress v. Troyer, 479 F.3d 1269, 1280 (10th Cir. 2007) (“An agency’s decision will be deemed arbitrary and capricious if the agency entirely failed to consider an important aspect of the problem[ ].... [or] failed to base its decision on consideration of the relevant factors....” (internal quotations and alterations omitted)).

We also reject Federal Appellees argument that “the site-specific APD EAs addressed cumulative drilling effects that differ in type and magnitude from those examined in the” 2003 EIS. Fed. Aples. Br. at 37. As discussed, the record indicates otherwise. None of the five EAs we consider contain any analysis of the cumulative impact to water resources from the 3,960 reasonably foreseeable horizontal Mancos Shale wells. And the record supports the conclusion that the water use associated with those 3,960 wells far exceeds the water use considered in the 2003 EIS. The 2003 EIS’s water-resources analysis was therefore not “sufficiently comprehensive or adequate” to support the proposed drilling, and the EAs were required to “provide any necessary analysis.” 43 C.F.R. § 46.140(b). Because they did not, the BLM violated NEPA.

Appellants have established that the water use associated with drilling the 3,960 reasonably foreseeable horizontal Mancos Shale wells exceeded the water use contemplated in the 2003 EIS in a way that made the BLM’s failure to consider the cumulative water impacts “significant enough to defeat the goals of informed decisionmaking and informed public comment.” Utahns for Better Transp, 305 F.3d at 1163. We conclude that the BLM acted arbitrarily and capriciously in issuing FONSIs and approving APDs associated with EAs 2014-0272, 2015-0036, 2015-0066, 2016-0029, and 2016-0200/2016-0076.

VII

“Under the APA, courts ‘shall’ ‘hold unlawful and set aside agency action’ that is found to be arbitrary or capricious.” WildEarth Guardians v. U.S. Bureau of Land Mgmt., 870 F.3d 1222, 1239 (10th Cir. 2017) (quoting 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(A)). “Vacatur of agency action is a common, and often appropriate form of injunctive relief granted by district courts.” Id. “In the past, we have done all of the following when placed in a similar posture: (1) reversed and remanded without instructions, (2) reversed and remanded with instructions to vacate, and (3) vacated agency decisions.” Id. (collecting cases). And remand to the agency is usually the appropriate decision in this situation. See Middle Rio Grande Conservancy Dist. v. Norton, 294 F.3d 1220, 1225–26 (10th Cir. 2002) (“[A] reviewing court normally remands when it finds an agency’s decision not to conduct an EIS arbitrary or capricious.”).

Given our remand instructions to vacate, however, there is no need to also “enjoin any further ground-disturbing activities on the APDs” as Appellants request. Aplts. Br. at 51. Once the APDs are vacated, drilling operations will have to stop because “[n]o drilling operations, nor surface disturbance preliminary thereto, may be commenced prior to” APD approval. 43 C.F.R. § 3162.3-1(c). Because vacatur is “sufficient to redress [Appellants’] injury, no recourse to the additional and extraordinary relief of an injunction [is] warranted.” Monsanto Co. v. Geertson Seed Farms, 561 U.S. 139, 166, 130 S.Ct. 2743, 177 L.Ed.2d 461 (2010).

VIII

All Citations

--- F.3d ----, 2019 WL 1999298

Footnotes |

|

Appellants are four environmental advocacy groups: (1) Diné Citizens Against Ruining Our Environment, comprised of Navajo community activists from the Four Corners region, (2) San Juan Citizens Alliance, concerned with social, economic, and environmental justice in the San Juan Basin, (3) WildEarth Guardians, based in Santa Fe, New Mexico and with members and offices throughout the western United States, and (4) Natural Resources Defense Council, with members throughout the United States, many of whom reside in New Mexico. |

|

The number of wells at issue on appeal is unclear. Although the district court ruled that twenty-eight challenged APDs are not final agency action and four others are moot—a ruling Appellants do not appeal—Appellants continue to assert that 362 APDs (the same number they argued throughout briefing in the district court) are at issue. Federal Appellees, for their part, assert that the challenged wells “number[ ] 337 as of October 17, 2018,” but cite only to the district court’s opinion in support. Fed. Aples. Br. at 18. |

|

Regardless, both of these requirements are met. Each organization has the goal of protecting the environment in some way. And nothing indicates that individual members would need to participate for the court to grant the relief Appellants request. |

|

Because “standing is determined at the time the action is brought,” Mink v. Suthers, 482 F.3d 1244, 1253 (10th Cir. 2007), it does not affect our standing analysis that these dates are now past. |

|

Although we dismissed the appeal in Palma for lack of ripeness, Palma still informs our injury-in-fact determination. Because we concluded that the Palma plaintiffs had established a concrete and particularized injury, we went on to consider “not whether SUWA is a proper party to challenge BLM’s decision, but when it can do so.” 707 F.3d at 1157. But our determination that the Palma plaintiffs’ harm was not ripe does not render obsolete our conclusion that their harm was sufficiently concrete and imminent. Palma therefore appropriately informs our injury-in-fact analysis here. |

|

The harms Appellants allege are the same for their NHPA claims (an increased risk of harm to Chaco Park and the surrounding area), and NHPA is also a procedural statute, so the standing analysis for NHPA is the same as for NEPA in this case. Appellants have established standing under NHPA because they allege a concrete and particularized injury in fact that is fairly traceable to the BLM’s alleged failure to comply with NHPA and could be redressed by a favorable decision. |

|

It appears that many CRSs and Records of Review analyze the impacts on historic properties for more than one APD. And it appears that most, if not all, EAs analyze the impacts of more than one APD. Regardless, the record on appeal contains far fewer than all of the documents containing the BLM’s NHPA analyses. |

|

We note that even as to these EAs, it is possible that the record does not contain the BLM’s entire NEPA analysis. See, e.g., JA2143 (stating “Appendix D. Surface Reclamation Plan,” but not containing any surface reclamation plan). However, because we do not identify—and the parties do not point to—any missing portion of these EAs relevant to the challenges Appellants raise on appeal, we conclude that the record is sufficient for us to evaluate Appellants’ NEPA claims as to these EAs. |

|

Although Appellants acknowledge the existence and applicability of the 2004 Protocol, they make no NHPA arguments under the 2004 Protocol. Federal Appellees assert (without citation) that “[a]pproximately 221 of the challenged drilling permits were approved at the time the 2004 Protocol was operative, and approximately 163 permits fell under the 2014 Protocol.” Fed. Aples. Br. at 12. All of Appellants’ NHPA arguments, however, rely on the 2014 Protocol. Because we conclude that Appellants’ NHPA challenge fails for other reasons, we need not address the effect Appellants’ failure to argue that the BLM violated the 2004 Protocol might otherwise have on Appellants’ NHPA challenges. |

|