129 F.Supp.3d 1069

United States District Court,

W.D. Washington,

At Seattle.

United States of America, et al, Plaintiffs,

v.

State of Washington, et al., Defendants.

No. C70–9213

|

Subproceeding No. 09–01

|

Signed July 9, 2015

Attorneys and Law Firms

*1071 Kerry Jane Keefe, US Attorney’s Office, Jane Garrett Steadman, Phillip Evan Katzen, Kanji & Katzen, Eric J. Nielsen, Nielsen, Broman & Koch, Seattle, WA, Vanessa Boyd Willard, US Department of Justice, Denver, CO, John William Ogan, Karnopp Petersen LLP, Bend, OR, Riyaz Amir Kanji, Kanji & Katzen, Ann Arbor, MI, James Rittenhouse Bellis, Suquamish Tribe, Suquamish, WA, Fawn R. Sharp, Tribal Attorney, Taholah, WA, Katherine K. Krueger, Quileute Natural Resources, Lapush, WA, Lori Ellen Nies, Raymond G. Dodge, Jr., Tribal Attorney, Skokomish Nation, WA, *1072 Emily Rae Hutchinson Haley, Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, James Miller Jannetta, Office of the Tribal Attorney, La Conner, WA, Thomas A. Zeilman, Law Office of Thomas A. Zeilman, Yakima, WA, for Plaintiffs.

Rene David Tomisser, Bryce E. Brown, Jr., Laura J. Watson, Noah Guzzo Purcell, Philip Michael Ferester, Terence A. Pruit, Laura J. Watson, Joseph V. Panesko, Michael S. Grossmann, Joseph Earl Shorin, III, Attorney General’s Office, Olympia, WA, for Defendants.

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND MEMORANDUM ORDER

RICARDO S. MARTINEZ, UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

I. INTRODUCTION

This subproceeding is before the Court pursuant to the request of the Makah Indian Tribe (the “Makah”) to determine the usual and accustomed fishing grounds (“U & A”) of the Quileute Indian Tribe (the “Quileute”) and the Quinault Indian Nation (the “Quinault”), to the extent not specifically determined by Judge Hugo Boldt in Final Decision # 1 of this case. The Court is specifically asked to determine the western boundaries of the U & As of the Quileute and Quinault in the Pacific Ocean, as well as the northern boundary of the Quileute’s U & A. A 23–day bench trial was held to adjudicate these boundaries, after which the Court received extensive supplemental briefing by the Makah, Quileute, Quinault, and numerous Interested Parties and took the matter under advisement. The Court has considered the vast evidence presented at trial, the exhibits admitted into evidence, trial, post-trial, and supplemental briefs, proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, and the arguments of counsel at trial and attendant hearings. The Court, being fully advised, now makes the following Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law. To the extent certain findings of fact may be deemed conclusions of law, or certain conclusions of law be deemed findings of fact, they shall each be considered conclusions or findings, respectively.

I. BACKGROUND

On February 12, 1974, Judge Hugo Boldt entered Final Decision # 1 in this case. The decision set forth usual and accustomed fishing grounds and stations (“U & As”) for fourteen tribes of western Washington, wherein the tribes had a treaty-secured right to take up to 50% of the harvestable number of fish that could be taken by all fishermen. See United States v. Washington, 384 F.Supp. 312 (W.D.Wash.1974) (“Final Decision 1 ”). The Court enforced its ruling through entry of a Permanent Injunction, whereby it provided for any party to the case to invoke the continuing jurisdiction of the Court on seven different grounds, the sixth of which permits adjudication of “the location of any of a tribe’s usual and accustomed fishing grounds not specifically determined by Final Decision # I.” Id. at 419 (Permanent Injunction, ¶ 25(a)(6)), as modified by the Court’s Order Modifying Paragraph 25, Dkt. # 13599.1 After innumerable subproceedings and appeals and multiple decisions from this country’s highest Court, this forty year-old injunction remains in place, safeguarding the rights reserved by these tribes in treating with the United States government to continue to fish as they had always done, beyond the boundaries of reservations to which they agreed to confine their homes.

*1073 It is under the jurisdiction set forth by the Permanent Injunction that the parties are again before this Court. The Makah Indian Tribe initiated this subproceeding on December 4, 2009 by filing a request for this Court to determine the usual and accustomed fishing grounds and stations of the Quileute Indian Tribe and the Quinault Indian Nation, to the extent not specifically determined by Judge Boldt in Final Decision # 1. In particular, the Makah ask the Court to define the western and northern boundaries of the Quileute U & A and the western boundary of the Quinault’s U & A in the Pacific Ocean—waters beyond the original case area considered by Judge Boldt.2 After a series of pre-trial rulings, this subproceeding proceeded to trial under Paragraph 25(a)(6) of the Permanent Injunction. See No. 09–01, Order on Motions, Dkt. # 304.

This is only the second subproceeding in the long history of this case in which this Court has been asked to rule on the boundaries of a tribe’s usual and accustomed fishing grounds in the Pacific Ocean. In the first such subproceeding, this Court in 1982 adjudicated the boundaries of the Makah Tribe’s Pacific Ocean U & A, determining its western boundary to be located forty miles offshore and its southern boundary to be located at a line drawn westerly from Norwegian Memorial. United States v. Washington, 626 F.Supp. 1405, 1467 (W.D.Wash.1985) (“Makah”), aff’d 730 F.2d 1314 (9th Cir.1984). Since that time, the Quileute and Quinault have been fishing at locations up to forty miles offshore under regulations adopted by the federal government pending formal adjudication by this Court. See No. 09–01, Dkt. # 304 at pp. 3–4.

The subproceeding was tried to the Court over the course of 23 days commencing March 2, 2015 and concluding April 22, 2015. The Court heard testimony from eleven witnesses and admitted 472 exhibits comprised of thousands of pages. The Court also heard argument and reviewed briefs by the Makah, Quileute, Quinault, and a number of Interested Parties, including the State of Washington and the Hoh, Port Gamble S’Klallam, Jamestown S’Klallam, Tulalip, Swinomish, Upper Skagit, Nisqually, Squaxin Island, Muckleshoot, Puyallup, and Suquamish Tribes. The Court commends counsel for each of these parties—and for the Makah, Quinault, and Quileute in particular—for their exhaustive, thorough, and diligent efforts throughout the course of trial and the proceedings leading up to it. Indeed, trial on these three boundaries exceeded the length of the original trial before Judge Boldt leading to Final Decision # 1, a reflection of the great care and extensive research time and resources invested by all parties to this case. It is with the utmost respect for the impassioned efforts and the sincere professionalism demonstrated by all parties during this unusually extensive trial, as well as for the profound investment of diverse communities in the decision rendered herein, that the Court sets forth the following findings of fact and conclusions of law.

II. FINDINGS OF FACT

The following findings of fact are based upon a preponderance of the evidence presented at trial. Where relevant, the Court also draws on findings of fact set forth by Judge Boldt in Final Decision # 1.

A. Treaty Background

As an initial matter, the Makah and Interested Party the State of Washington *1074 are at odds with the Quileute, Quinault, and a number of Interested Party tribes with respect to the scope of the treaty-secured “right of taking fish.” Specifically, the parties dispute whether evidence of a tribe’s harvest of marine mammals, including fur seals and whales, may be the basis for establishing a tribe’s U & A. The Makah and the State, joined by three Interested Parties, take the position that a tribe’s U & A must be established on the basis of locations where it went at treaty time for the purpose of taking finfish. By contrast, the Quileute and Quinault, with support from a number of Interested Parties, argue for a construction of their treaty that would allow for a U & A to be established based on a broader interpretation of “fish” inclusive of evidence of a tribe’s treaty-time marine mammal harvest activities. The following findings of fact concerning the background of tribal treaty rights are made in answer to the question of treaty interpretation raised by the parties.

1. General Context of Treaty Negotiations

1.1. On August 30, 1854, Isaac Stevens, the first Governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs of the Washington Territory, was notified of his appointment to negotiate treaties with tribes west of the Cascade Range (hereinafter, the “Stevens Treaties”). The principal purposes of the Stevens Treaties were to extinguish Indian claims to the land in Washington Territory and to provide for peaceful and compatible coexistence of Indians and non-Indians in the area. Governor Stevens and the treaty commissioners who worked with him were not authorized to grant to the Indians or treat away on behalf of the United States any governmental authority of the United States. Final Decision 1, Findings of Fact (“FF”) 17, 19.

1.2. At the treaty negotiations, a primary concern of the Indians whose way of life was so heavily dependent upon harvesting fish, was that they have freedom to move about to gather food at their usual and accustomed fishing places. In 1856, it was felt that the development of the non-Indian fisheries in the case area would not interfere with the subsistence of the Indians, and Governor Stevens and the treaty commissioners assured the Indians that they would be allowed to continue their fishing activities. FF 20.

1.3. It was the intention of the United States in negotiating the treaties to make at least non-coastal tribes agriculturists, to diversify Indian economy, and to otherwise facilitate the tribes’ assimilation into non-Indian culture. There was no intent, however to prevent the Indians from using the fisheries for economic gain. FF 21.

1.4. There is nothing in the written records of the treaty councils or other accounts of discussions with the Indians to indicate that the Indians were told that their existing fishing activities or tribal control over them would in any way be restricted or impaired by their treaty. The most that could be implied from the treaty context is that the Indians may have been told or understood that non-Indians would be allowed to take fish at the Indian fishing locations along with the Indians. FF 26.

1.5. Since the vast majority of the Indians at the treaty councils did not speak or understand English, the treaty provisions and the remarks of the treaty commissioners were interpreted by Colonel Benjamin F. Shaw, the treaty commission’s official interpreter, to the Indians in Chinook jargon and then translated into native languages by Indian interpreters. Chinook jargon, a trade medium of limited grammar and a vocabulary of only 300 or so terms, was inadequate to express precisely the legal effects of the treaties, although the general meaning of treaty language *1075 could be explained. Even so, many of those present did not understand Chinook jargon. There is also no record of the Chinook jargon phrase that was actually used in the treaty negotiations to interpret the provision for the “right of taking fish.” FF 22; see also Ex. 64.

2. Treaties with the Makah, Quileute, and Quinault

2.1. The Makah were a party to the Treaty of Neah Bay, signed on January 31, 1855. The Treaty of Neah Bay was negotiated with the Makah by Governor Stevens and members of his treaty commission, including George Gibbs (a lawyer and adviser to Stevens), Colonel Michael Simmons, and Colonel Shaw. Gibbs maintained a journal that includes a still extent record of the treaty negotiations with the Makah. It appears from Gibbs’ journal that tribes to the south of the Makah, likely including the Quileute, were invited to attend the treaty council, but Governor Stevens decided to proceed without them to avoid delaying the negotiations. The Treaty of Neah Bay was ratified by the United States Senate on March 8, 1859, and proclaimed by the President on April 18, 1859. A reserved fishing rights provision is found in Article 4 of the Treaty of Neah Bay, which provides as follows:

The right of taking fish and of whaling or sealing at usual and accustomed grounds and stations is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the United States and of erecting temporary houses for the purposes of curing, together with the privilege of housing and gathering roots and berries on open and unclaimed lands: Provided, however, That they shall not take shell-fish from any beds staked or cultivated by citizens.

Ex. 29 at pp. 1, 4; Ex. 65 at p. 19 (journal of George Gibbs, recording decision to send for the “other tribes” to meet at Grays Harbor); Ex. 298.

2.2. Governor Stevens, along with Gibbs, Simmons, and Shaw, first attempted to negotiate a treaty with the Quinault and other tribes in southwest Washington in February 1855 at the Chehalis River Council. As with the Treaty of Neah Bay, Gibbs’ journal provides a record, albeit a likely incomplete one, of the failed Chehalis River negotiations. The Quileute were not represented at the Council, although they sent two boys along with the Quinault to observe. The Chehalis River Council was intended to treat with the remaining tribes of Washington Territory west of the Cascade Range. However, it was accidentally discovered at the council, perhaps upon negotiators’ overhearing the different language spoken by the two Quileute boys, that the Quinault did not occupy the entire area between the Chehalis River and Makah territory and that a distinct tribe—the Quileute—was situated between the two. Gibbs attributed the exclusion of the Quileute to their speaking a different language from the Quinault such that messengers sent up the coast to provide notice of the council had not communicated with the tribe. For these reasons, the Quileute were omitted from the negotiations. The Chehalis River negotiations ultimately broke down when participating tribes refused to agree to Governor Stevens’ proposal that a single reservation be established for all of the tribes. See Ex. 65 at pdf pp. 23–24; Ex. 68 at pp. 172–73.

2.3. The Quileute and Quinault, together with the Hoh Tribe, were ultimately parties to the Treaty of Olympia, negotiated a few months later on July 1, 1855 at a village at the mouth of the Quinault River, now known as Taholah. Tr. 3/3 at 19:3–7 (Hoard). When the Treaty of Olympia was negotiated, only half of the four-member U.S. treaty commission was present: both Governor Stevens and George Gibbs were absent, and Stevens sent Colonel Simmons to negotiate in his stead, with *1076 Shaw serving as interpreter. Simmons utilized the draft treaty developed at the Chehalis River negotiations. As a result, the only substantive difference between the two is that the Treaty of Olympia provides that more than one reservation might be established for the Quileute and Quinault. There is no surviving journal of the negotiations conducted by Simmons. The Treaty of Olympia was signed by Governor Stevens in Olympia on January 25, 1856, ratified by the United States Senate on March 8, 1859 and proclaimed by the President on April 11, 1859. Article 3 of the Treaty of Olympia contains the following reservation of rights provision:

The right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations is secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory, and of erecting temporary houses for the purpose of curing the same; together with the privilege of hunting, gathering roots and berries, and pasturing their horses on all open and unclaimed lands. Provided, however, That they shall not take shell-fish from any beds staked or cultivated by citizens; and provided, also, that they shall alter all stallions not intended for breeding, and keep up and confine the stallions themselves.

Ex. 297.

2.4. Not all of the differences between treaties can be attributed to differing degrees of importance that tribes attached to various resources. For instance, a provision for pasturing horses is absent from the Treaty of Neah Bay but present in both the Treaty of Olympia and the draft Chehalis River Treaty. It is probable that Governor Stevens included this provision deliberately in the draft Chehalis River Treaty in response to specific concerns of the Chehalis and Cowlitz tribes for maintaining their horse traditions. By contrast, the fact that the draft Chehalis River Treaty was used as a template for the Treaty of Olympia most likely explains the inclusion of this provision in the treaty with the Quinault and Quileute. In particular, the limited use of horses by the Quileute Tribe makes the inclusion of this provision in the Treaty of Olympia anomalous. Stevens, unlike Simmons, was invested with authority to tailor treaty provisions in response to needs and concerns expressed by the tribes. As Governor Stevens was absent from the Treaty of Olympia negotiations, the ability of the Quileute and the Quinault to negotiate tailored treaty provisions was most likely limited. See Tr. 3/16 at 182:13—184:18; 192:3–10 (Boxburger).3

3. Scope of the Right of Taking Fish

3.1. Although the treaty commission was primarily concerned with obtaining land, see Tr. 3/16 at p. 187:18–22 (Boxburger), the minutes that are available indicate a persistent concern among the Indians with preserving their entire subsistence cycle. For instance, when Che-lan-the-tat of the Skokomish Tribe expressed a concern at the negotiation of the Treaty of Point–No–Point with the ability of the tribes to feed themselves upon ceding so much land, Benjamin Shaw assured the tribes that they were “not called upon to give up their old modes of living and places of seeking food, but only to confine their houses to one spot.” Ex. 65 at p. 11. Governor Stevens informed the tribes at that same council that the treaty “secures [their] fish.” Id. at p. 14. Stevens similarly informed the tribes at the Chehalis River Council that the members of the treaty commission “want you to take fish where *1077 you have always done so and in common with the whites.” Id. at p. 22.

3.2. The minutes from the Chehalis River negotiations indicate that the participating tribes were specifically concerned with reserving the right to take sea mammals. During the Chehalis River negotiations, the assembled Indians raised the issue of whales at least twice. Tuleh-uk, the head chief of the Lower Chehalis, stated, “I want to take and dry salmon and not be driven off ... I want the beach. Everything that comes ashore is mine (Whales and wrecks.) I want the privilege of the berries (Cranberry Marsh).” Governor Stevens responded, “He (Tuleh-uk) sees that we write down all that he says ... That paper (the Treaty) was the heart of the Great Father which he thought good. It said he should have the right to fish in common with the whites, and get roots and berries.” Ex. 65 at p. 24. Stevens’ response to Tuleh-uk suggests that the term “fish” was used in a capacious sense, encompassing finfish as well as whales. See Tr. 3/3 at pp. 34:1–35:21 (Hoard). While Stevens elsewhere distinguished between “fish” and “whales” in responding to a demand from representatives of the Chinook Tribe for “one half of all that came ashore on the weather beach,” he made no distinction between the tribes’ right to take beached whales and to hunt for swimming whales. See Ex. 65 at p. 26 (“They of course were to fish etc. as usual. As to whales, they were theirs....”); TR 3/3 at pp. 36:5–39:1 (Hoard).

3.3. Although the draft treaty was read to the assembled tribal representatives, no objection was made despite the lack of an express reference to the right to take sea mammals. See Ex. 65 at p. 32. It is reasonable to infer from the absence of any objection that the tribes understood the right to take whales to be provided for in the treaty. See 3/3 Tr. at pp. 45:13–25; 78:1–79:7 (Hoard).

3.4. Nothing in the record of the negotiations of any of the treaties indicates that the U.S. treaty commission intended to exclude the harvest of sea mammals from the tribes’ reserved fishing rights. By contrast, the intent to include the harvest of sea mammals is corroborated by James Swan’s record of the treaty negotiations. Swan recounts that “[t]he Indians, however, were not to be restricted to the reservation, but were to be allowed to procure their food as they had always done, and were at liberty at any time to leave the reservation to trade with or work for the whites.” Ex. 291 at p. 344. It is reasonable to infer from Swan’s statement that Governor Stevens intended the treaties to reserve to tribes that had customarily harvested sea mammals the right to continue to do so “as they had always done.”

3.5. Dictionary definitions at the time also evidence a broad popular understanding of the word “fish.” For instance, the 1828 Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language defined “fish” expansively as “[a]n animal that lives in the water.” Ex. 334. While the dictionary recognized the Linnaean taxonomic classification of “fish,” which limited the term to aquatic animals that “breathe by means of gills, swim by the aid of fins, and are oviparous,” it nonetheless acknowledged its broader popular meaning: “Cetaceous animals, as the whale and dolphin, are, in popular language, called fishes, and have been so classified by some naturalists.... The term fish has also been extended to other aquatic animals, such as shell-fish, lobsters, etc.” Id. (emphasis in original). Other dictionaries from the time corroborate the term’s broad meaning in popular usage. See, e.g., Ex. B222.6 (quoting Worcester’s 1860 dictionary and Walker’s 1831 dictionary, which both define fish as “an animal that inhabits the water”); 3/3 Tr. pp. 52:15, 56:4–57:25, 202:22–203:12 (Hoard). The common usage in legal opinions *1078 from the mid to late 1800s of the terms “fish” and “fisheries” in reference to both whales and seals suggests that the U.S. treaty negotiators may themselves have intended to use the term “fish” in its broadest sense. See, e.g., In re Fossat, 69 U.S. 2 Wall. 649, 696, 17 L.Ed. 739 (1864) (“For all the purposes of common life the whale is called a fish, though natural history tells us that he belongs to another order of animals.”); Ex parte Cooper, 143 U.S. 472, 499, 12 S.Ct. 453, 36 L.Ed. 232 (1892) (discussing “seal fisheries”); The Coquitlam, 77 F. 744, 747 (9th Cir.1896) (“They all had the usual ships’ supplies and stores and outfit for seal fishing.”).

3.6. There is no record of the Chinook phrase that was actually used to communicate the “right of taking fish.” FF. 22. The severe limitations of Chinook jargon as a medium for communication, as well as the limited familiarity of negotiators on both sides with the language, inhibited the capacity to communicate treaty terms with precision. The negotiators most likely used the Chinook word “pish,” translated by George Gibbs in his 1863 “Dictionary of the Chinook Jargon” as “English. Fish.” Ex. 64 at p. 26. The negotiators may also have used the Chinook phrases “mamook pish” or “iskum pish,” meaning “to take fish” or “to get fish.” See Tr. 3/3 at pp. 66:6–67:24 (Hoard). While Chinook jargon did contain terms for some individual aquatic species, including whales, seals, and salmon, it lacked cover (i.e.high-level) terms that could differentiate between taxa or larger groupings of aquatic animals, such as finfish, shellfish, cetaceans, and sea mammals. See Ex. 64. It is reasonable to infer that the negotiators employed broad cover terms from Chinook jargon when negotiating the fishing rights provision and that these cover terms would not have been used in a restrictive sense. See Tr. 3/3 at p. 68:7 (Hoard).

3.7. The sweep of the words for “fish” in the Quileute and Quinault languages is even broader than in Chinook jargon. The Quinault cover term for “fish,” “Kémken,” is defined alternatively as “salmon,” “fish,” and “food.” See Ex. 76. Similarly, the Quileute cover term, “?aàlita?” is translated by multiple lexicographers as “fish, food, salmon.” Exs. 225, 233. As with the Chinook jargon, neither tribe’s language possessed terms that could differentiate between groupings of aquatic species, such as sea mammals, shellfish, and finfish. It is reasonable to infer from the records of the Quileute and Quinault languages that members of these tribes would have understood that the treaty reserved to them the right to take aquatic animals, including shellfish and sea mammals, as they had customarily done.

3.8. Post-treaty activities also suggest that all parties to the Treaty of Olympia understood its subsistence provision to secure to the Quinault and Quileute the right to take whales and seals at their usual and accustomed harvest grounds. During the post-treaty period, these tribes continued to harvest whales and seals from the Pacific Ocean without any protest from government agents. To the contrary, Indian agents actively encouraged these tribes to continue their sea mammal harvest. For instance, Indian Agent Charles Willoughby urged the Quileute to “continue your fisheries of salmon and seals and whales as usual” and assured them that if they wanted any blacksmith work done, such as “spear heads for seals or harpoons for whales, the blacksmith at the agency at Neah Bay will do the work.” Ex. 281 at pp. 165, 167. These two tribes were also among those along the coast of the United States and Canada that were exempted from restrictions on fur sealing imposed through the 1893 Bering Sea Arbitration Award and 1894 Bering Sea Arbitration Act. See Ex. B85 at p. 53. Post-treaty *1079 activities are thus consistent with the reservation of the right to harvest sea mammals in the Treaty of Olympia and inconsistent with a restrictive reading of the treaty’s fishing rights provision.

A. Quinault Indian Nation’s Western Boundary

1. Background on Traditional Quinault Economy

4.1. There is comparatively little documented information about aboriginal Quinault culture and subsistence fishing activity relative to information about other western Washington tribes. Evidence regarding treaty-time activities of the Quinault is limited even in comparison to the similarly isolated Quileute and substantially more limited than for the Makah, whose location amidst the deep harbors at Neah Bay made this latter tribe unusually accessible to non-Indian traders, settlers, and visitors. Tr. 3/16 at 4:22–25 (Boxburger).

4.2. Treaty-time governmental contacts with the Quinault were few. In 1854, just prior to the Treaty of Olympia negotiations, George Gibbs wrote, “Following up on the coast, there is another tribe upon the Kwinaitl [Quinault] River, which runs into the Pacific some twenty-five miles above the Chihalis, its headwaters interlocking with the streams running into Hood’s canal and the inlets of Puget sound. Little is known of them except that they speak a different language from the last.” Ex. B90 at p. 426. Federal Indian agent reports about the Quinault were all written post-treaty and focus on activities with the potential for commercial development to aid in the government’s assimilation policy. These reports, narrow in their purview, are consequently of limited utility in discerning Quinault treaty-time practices. See Tr. 3/30 at p. 99 (Thompson); Tr. 4/2 at pp. 65–68 (Renker).

4.3. There have been no archaeological excavations that have generated data associated with aboriginal Quinault occupancy. See Tr. 4/7 at pp. 101–103 (Wessen). The only recorded pre-treaty historical accounts that mention the Quinault consist of records of a 1775 encounter with the Spanish vessel Sonora (an encounter that some scholars attribute to the Quileute rather than the Quinault, see Ex. 255 at p. 97 & n. 34), a 1788 encounter with English explorers on the Columbia expedition, and accounts by James Swan of his three-day trip to Quinault in 1854 as well as an encounter with several Quinault Indians while Swan was living 60 miles south of Quinault in Shoalwater Bay. One of nine accounts of the Wilkes Expedition also records an encounter with canoes carrying some men “from southward about Grays Harbor” at the western end of the Strait of Juan de Fuca on August 3, 1841. Ex. B200 at pdf p. 5. These men may have been Quinault. TR 3/18 at pp. 175–178 (Boxburger).

4.4. Most of what is known about Quinault culture and subsistence activities before and at treaty times comes from Dr. Ronald Olson’s ethnology of the Quinault. Dr. Olson conducted anthropological fieldwork at Quinault for one month each in the spring of 1925 and the winters of 1925–26 and 1926–27 and published an ethnography on the Quinault in 1936. Ex. 213. Dr. Olson’s ethnography intended to describe Quinault culture and society prior to contact with non-natives and drew from the memories and oral histories of informants, whom Dr. Olson described as “thoroughly reliable, reasonably intelligent” and “familiar with the old life.” Ex. 213 at p. 3. Some of these informants, all of whom were over 60 years of age, had memories reaching back to the 1850’s. Ex. 212 at p. 696. Dr. Olson’s field notes are available in addition to his 1936 ethnography, though it is uncertain whether the remaining field notes are complete. Ex. 211. Dr. Olson also testified before the Indian *1080 Court of Claims (“ICC”) on behalf of the Quinault in 1956. Ex. 212.

4.5. The Quinault occupied the coast of Washington State for thousands of years. Tr. 3/16 at p. 2 (Boxburger). The current members of the Quinault Tribe are descendants of the treaty-time occupants of the villages situated in the territory extending roughly between the Queets River system to the north and the north shore of Gray’s Harbor to the south. Ex. 141 at p. 1 (1973 Lane Report). Chief Tahola, Head Chief for the Quinault, expressed the important relationship of the tribe to these traditional lands in his remarks to Governor Stevens at the Chehalis River Council: “He wanted his country. His children live there and wanted food. He wanted them to get it there, did not want to leave it. The river he did not want to sell near the salt water, nor the sand beach mouth, but that part above the mountains and off the river he would sell.” Ex. 65 at p. 23.

4.6. Fishing constituted the principal economic activity of the Quinault at treaty time. Salmon and steelhead served as the principal food and as an important item of trade for the tribe. FF 122. Gibbs remarked that the Quinault Tribe is “celebrated for its salmon, which are considered to excel in quality even those of the Columbia.” Ex. 68 at p. 172. The large, glacier-fed rivers in the Quinault region provided a rich source of salmon for the tribe. Reflecting the Quinault’s adaptation to extracting resources from this environment, Judge Boldt included a number of rivers and streams in his determination of the Quinault U & A within the original case area: Clear water, Queets, Salmon, Quinault (including Lake Quinault and the Upper Quinault tributaries), Raft, Moclips, Copalis, and Joe Creek. FF 120.

4.7. At the same time, the position of the Quinault on the Olympic Peninsula coast played an undeniable role in shaping and orienting the tribe’s culture, trade, and economic activities. See Ex. 213 at p. 12 (“The location of the Quinault on the open coast had its influence on their life.”). Comparing their Quinault to their northern neighbors, the anthropologist Jay Powell explained that, despite many Quileute families maintain settlements along inland river courses, “the Quileute, like their neighbors (the Quinaults, Ozettes, and Makahs), were primarily seafarers, deriving most of their livelihood from the oceans.” Ex. 224, p. 105. Intermarriages between the Quinault and members of tribes to the north and south were common in traditional Quinault society, as was inter-tribal trade along the coast. Ex. 213 at p. 13; Ex. 277 at p. 81–84. Before and at treaty time, the Quinault, whom Dr. Olson described as “expert canoemen,” possessed large ocean going canoes that they manufactured themselves or obtained in trade from the Makah and the Quileute. Id. at pp. 68, 73. The Quinault also manufactured sails out of cedar mats and used bailers and inflated sealskins to aid them in traveling on ocean voyages. Id. at p. 72. Before and at treaty time, the Quinault regularly traveled the Washington coast between Cape Flattery and the Columbia River. Id. at p. 87; Ex. B200 at pdf p. 5 (1841 report documenting encounter with Indians from Grays Harbor near Cape Flattery). The important linkage between the Quinault’s coastal location and the tribe’s subsistence practices is reflected in Judge Boldt’s determination that, in addition to inland fisheries, the Quinault utilized “[o]cean fisheries ... in the waters adjacent to their territory.” FF 120.

4.8. In addition to salmon, the Quinault made use of a wide variety of aquatic coastal and oceanic resources for food as well as for materials such as clothing, bedding, ropes, containers, and tools. For instance, Captain Willoughby, who served as Indian agent at Neah Bay prior to serving as Indian agent on the Quinault *1081 Reservation, recorded a wide range of plants and animals harvested by the tribe for food, including “[m]any varieties of salmon,” “tender shoots of rushes, young salmon-berry sprouts and other succulent growth of the spring-time,” bulbous roots, a wide range of berries, whale, seal, otter, deer, bear, elk, sea-gulls, ducks, geese, seaweed, and a variety of shellfish. Ex. 351 at pp. 269–70. In addition to many of these species, Dr. Olson noted Quinault harvest of halibut, cod, rock cod, sea bass, and sole. Ex. 213 at p. 36. The Quinault traditionally hunted for sea mammals, including whales, fur and hair (harbor) seals, sea otters, and sea lions. The Quinault both ate the flesh of seals and whales and used them to extract oil. They also traditionally made use of seal skins, as well as the skins of elk, bear, and rabbit, for clothing. Ex. 351 at p. 3. Skins of hair seals were used as buoys on whaling expeditions. Ex. 213 at p. 44. Sarah Willoughby, Captain Willoughby’s wife, included many of these products in her 1887 description of the possessions of a man named Riley, a Haida Indian and former slave who shared a lodge at Quinault with three other families. Among Riley’s possessions, Sarah Willoughby noted: “[g]reat skins of seal and whale oil,” “long festoons of whale blubber and dried clams,” “baskets of dried halibut and salmon,” “the skins of a beautiful sea otter,” three large bear skins, and other products obtained either locally or by trade. Ex. 355 at pdf pp. 2–4. The anthropologist Ram Raj Prasad Singh listed a similarly broad range of food resources traditionally used by the Quinault on a regular, seasonal basis. Among marine resources, Singh included: sea trout, night smelt, sea lion, blueback, candlefish, fur seal, salmon, whale, sea otter, smelt, and silver and king salmon. He also noted “some deep sea fishing” occurring from April through June. Ex. 277 at p. 67. Much of the salmon, halibut, rock cod, and bass caught by the Quinault were preserved for later consumption. Ex. 142 at p. 11.

4.9. Traditional Quinault culture did not recognize the “idea of ownership of land beyond a ‘use ownership’ of the house site.” Ex. 213 at p. 115. Individuals owned canoes and implements and could also own guardian spirits. Id. The concept of ownership did not extend to coastal and oceanic fishing grounds.

4.10. The Quinault possessed the navigational skills, knowledge, and technologies to travel extensively on the open ocean out of sight of land. Reflective of their oceanic navigational skills, the Quinault recognized six directions, one of which was expressed alternatively as “ocean side” and “far out to the ocean.” Ex. 213 at p. 178. The Quinault navigated chiefly by means of the sun but also watched the ocean swells when at sea, as they were said to always come from the west. Id. A few Quinault shamans were said to be able to control the weather. Id. at p. 150. The Quinault also had knowledge of the constellations, including of the Pole-star, which was known to be used by the Makah to navigate at night while whaling. Id. at pp. 177–78; Ex. 332 at p. 47. In consideration of this and other evidence, the noted anthropologist Dr. Barbara Lane wrote in a 1977 report on Quinault fisheries that “the record is clear that the Quinault possessed seaworthy canoes, navigational skills, and gear and techniques designed to harvest a variety of offshore fisheries and that they customarily did so.” Ex. 142 at p. 12.

2. Quinault Offshore Fishing

5.1. At and before treaty time, the Quinault engaged in offshore fisheries on a regular, seasonal basis for salmon, halibut, cod, rock cod, sea bass, sole, smelt, candlefish, and herring. Ex. 213 at pp. 36–38. The Quinault harvested smelt and candlefish *1082 by means of a dip net, and caught halibut, cod, rock cod, and sea bass with hook and line. Id. Herring were harvested with a herring rake used from a canoe. Id. at p. 38. The Quinault also regularly harvested razor clams, mud clams, oysters, mussels, sea anemones, and crabs along the shore. Id. at pp. 38–39. During the summer months, some Quinault migrated from their upland villages to sites along the coast to engage in these ocean fisheries. Id. at p. 38; Ex. 277 at p. 71.

5.2. Dr. Olson recorded some of the usual locations and distances at which these offshore fish species were customarily harvested by the Quinault at and before treaty time. Smelt and candlefish were taken by the people of the lower villages at the river mouth and at the surf of the beach, and herring was taken within a mile of the beach. Ex. 213 at pp. 36–38. Halibut, cod, rock cod, sea bass, and sole “could be taken anywhere along the coast within six miles of shore.” Id. One of Dr. Olson’s informants reported that halibut, rock cod, and bass were fished in an identical manner between July and August at locations five to six miles offshore, in waters close to rocks and approximately twenty-five feet deep. Ex. 211 at pdf p. 28.

5.3. Although the Quinault most likely harvested these fish within six miles, they may have fished at distances further offshore on at least an occasional basis. Dr. Lane, for instance, concluded in her 1977 report on Quinault ocean fisheries that, while “[i]t is not feasible to document the outer limits of Quinault fishing, [ ] it appears that Quinault fishermen were familiar with offshore resources for at least thirty miles west of the Olympic peninsula.” Ex. 142 at p. 1. Evidencing this familiarity, unidentified Indians informed the United States Fish Commission of a fishing bank at the continental shelf, approximately 30 miles offshore from Shoalwater Bay. Ex. 318 at p. 65. In 1895, Beriah Brown wrote an article on Quinault marine mammal hunting, in which he noted that the fur seal stop at this bank on their migration northward, where many of them fall victim to the Quinault. Brown described this bank as a “famous [ ] fishing ground.” Ex. 18 at pdf p. 2. More likely than not, the Quinault Indians were the ones who informed the U.S. Commission of the location of the bank, given that they frequented Shoalwater Bay at treaty-time and ranged 30 miles offshore in their marine mammals hunts. The Quinault also manufactured fishing lines two to three hundred fathoms in length, which would be consistent with deep-sea fishing practices. Ex. 211 at pdf p. 675.

3. Quinault Whaling

6.1. Whaling has been consistently recognized as an important cultural and economical tradition is pre-treaty Quinault society. While Quinault, like other coastal tribes, made use of drift whales that beached on their territorial coast, the historical and ethnographic evidence demonstrates that the active pursuit of whales was a deeply engrained practice in Quinault society. Dr. Olson, for instance, described the Quinault as the “most southern people who engaged in the pursuit of whales.” Ex. 213 at p. 12. While Dr. Olson was of the opinion that the abundance of salmon in Quinault Territory mitigated the tribe’s need and desire to engage in whaling to the extent of the Makah and Quileute to the north, he nonetheless recognized the importance of the practice in Quinault society, as manifested by traditional Quinault secret societies dedicated to whaling and of rituals associated with the hunt. Id. See id. at p. 44 (describing whaling as a “dangerous and spectacular pursuits [ ] hedged about with ritual.”). Dr. Olson recorded only two Quinault whalers—Nicagwa’ts and his brother—active around 1850, though he reported that there were as *1083 many as six Quinault whalers at any time in the pre-treaty era, when the population was larger. As each whaler would have needed to “call together seven other men to aid him,” id. the number of individuals engaged in whaling in 1850 would have been a substantial proportion of the population, which consisted of only 158 Quinault according to a treaty-time census. Tr. 3/16 at 60:2–18 (Boxburger). Edward Curtis, a Seattle photographer who visited Quinault in 1910, gave a similar account of the existence of two Quinault whalers at treaty-time, each captaining a canoe of eight men in total. Ex. 347 at pp. 9–10.

6.2. Quinault whalers traditionally made use of large ocean canoes, sufficient to fit six paddlers, the steersman, and the harpoon thrower, who also served as the head whaler. The Quinault whalers made use of a harpoon similar to that used by the Makah as well as buoys made of whole skins of hair seal.

6.3. A generations old myth describes how the Quinault learned to hunt whales. The “Story of the Dog Children,” recorded by Livingston Farrand, tells of five children who could change from human to dog form. Cast away from society, the children learned to hunt whales from their mother using sealskin floats and harpoons. When their whaling prowess was discovered by the villagers, the children were welcomed back into society, becoming chiefs of the village and always keeping the people well supplied with whales. Ex. 52 at pp. 127–28. The myth expresses the substantial time depth of the Quinault whaling tradition as well as its important place in Quinault identity and culture.

6.4. Quinault whaling was a specialized occupation. A Quinault whaler spent much of the year making and repairing the necessary equipment, which included a large ocean canoe and considerable other valuable gear. The head whaler had to possess the requisite guardian spirit, called sláo’ltcu, which was acquired shortly after puberty. In addition, a whaler went through a month of training previous to the season of whaling. During this period, the whaler bathed in a ritualized fashion each night in the ocean or river, went out alone in his canoe to practice throwing his harpoon and to converse with his spirit, and refrained from sexual intercourse for ten days prior to the hunt. Id. at pp. 44–46.

6.5. Whale products played an important role in the Quinault diet, economy, and ceremonial traditions. Whale meat was cured for later consumption and the blubber rendered into oil that was used as a condiment and in ceremonies and rituals. Dried foods were traditionally dipped into whale oil before they were eaten, and rendered whale fat was stored in the stomachs of seal or sea lion and in bags made from sections of whale intestines. Ex. 142 at p. 10.

6.6. Treaty-time historical accounts are consistent with customary Quinault whaling practices. During the first recorded contact with the Sonora in 1775, Indians (likely Quinault though possibly Quileute) offered whale meat to the Spanish sailors. The second recorded contact between Quinault and non-natives occurred in 1788, when the English ship Columbia encountered two whaling canoes with whaling implements from the village of Quinault. Around treaty-time, James Swan also came to know a famous Quinault whaler named Neshwarts, who was most likely the same whaler, Nicagwa’ts, reported by Dr. Olson. Ex. 283 at pp. 85–86; Tr. 3/16 at 104:5–105:18. Swan’s descriptions of Neshwarts indicate that Swan was familiar with the Quinault whaling tradition.

6.7. The substantial number of words in the Quinault language associated with whaling practices is also indicative of the time depth of the Quinault whaling tradition. *1084 Quinault have separate words for whale, little whale, whale blubber, whale bone, whale oil, and whaling canoe. Ex 176 at p. 315. The Quinault language also contains words indicative of ocean-going practices, including words meaning to “navigate on the ocean” and ocean canoe. Id. at p. 281.

6.8. The historical and ethnographic evidence shows that before and at treaty time, whaling was a regular and customary subsistence practice exercised by the Quinault, taking place each year on a seasonal basis during the summer months when Quinault Indians would migrate from upland coastal villages to participate in the hunt. According to Dr. Olson, the Quinault whaled each year from May to August, when a Quinault whaler would spend much of his time on the open water, “cruising for the animals.” Ex. 213 at p. 24. Singh too included whaling in his description of the Quinault’s seasonal rounds, taking place during these summer months. Ex. 277 at p. 67. One of Dr. Olson’s Quinault informants related that his grandfather, who would have lived before treaty time, harpooned 77 whales in his lifetime, a feat that would have required hunting whales regularly during the summer season. Ex. 213 at p. 155; Tr. 3/16 at pp. 53–54 (Boxburger). The summer season of active whale hunts stands in contrast to the winter season, when the waters were typically too turbulent for the tribe to venture far offshore but a drift whale or two would often make its way to the Quinault coast. See Ex. 211 at pdf p. 308.

6.9. The few ethnographic and historical accounts that exist of Quinault whaling show that the whaling voyages regularly required Quinault whalers to go up to 30 miles offshore on their hunts. Dr. Olson, for instance, records that “[w]hales were most often encountered 12 to 30 miles off shore.” Ex. 213 at p. 44. Dr. Olson testified at the 1956 ICC hearing that Quinault hunted whale in the open ocean, “going as far out as 25 miles or even more to harpoon and capture whale.” Ex. 212 at p. 514. When pressed about the western boundary of the Quinault territory, Dr. Olson testified that the Quinault “used to go out as much as 25 miles hunting whale.” Id. at p. 503. Dr. Lane agreed with these distances. See Ex. 142 at p. 4 (“In contrast to the herring which could be taken quite close to shore, whales and seals were harvested as far as twenty-five and thirty miles offshore.”).

6.10. Indian whaling canoes could also expect to be towed many miles out to sea as part of their hunt. See Ex. 260, pp. 18–19 (account by Dr. Lane of Makah whale hunt); Tr. 3/30 at p. 73:16–20 (Thompson). In his description of the traditional Quinault whale hunt, Dr. Olson noted that after a whale was struck by a harpoon, the whale “might run as much as ten to fifteen miles before being killed.” Id. at p. 45. A whaler with particularly strong power, such as Nicagwa’ts, was able to spur the whale to run toward shore instead of out to sea. According to Dr. Olson, Nicagwa’ts was never forced to tow a whale more than five miles, which would be consistent with harpooning a whale up to twenty miles offshore. Id.

6.11. The length of time needed for a single whale hunt is consistent with whaling practices taking place far offshore. Singh, for instance, noted that hunting a whale could require two or three days. Ex. 277 at p. 41. Among the various rituals and cultural taboos associated with whaling, Dr. Olson recorded the belief that should a whaler’s wife be unfaithful while her husband was away on a hunt, “the whale would be wary and ‘wild,’ and the men would be unable to kill any.” Ex. 213 at p. 46.

*1085 6.12. Hunts taking place at distances 20 to 30 miles offshore would have placed Quinault whalers at the edge of the continental shelf, a location where whales would have been found in abundance during the summer months. See Tr. at 3/9, pp. 103:22–105:24 (Trites). The continental margin starts at 20 miles offshore at the Quinault canyon and runs, on average, 30 miles offshore adjacent to Quinault territory. Id. at 105:15–24. Biologist Dr. Andrew Trites described this margin as an ocean “Serengeti,” through which large herds of marine animals, including whales and fur seals, would migrate on a seasonal basis. Id. at 104:8–23. The Court finds the testimony of Dr. Trites credible and consistent with traditional Quinault whaling voyages taking place at the distances described by Dr. Olson and other anthropologists.

4. Quinault Fur Sealing

7.1. The evidence also shows that fur sealing was traditionally practiced by the Quinault at and before treaty time. As with whaling, the Quinault language contains words specifically associated with fur sealing, including words for fur seal (“ma·a’i”), little seal, seal oil, and sealing canoe. Ex. 213 at p. 49, Ex. 176 at p. 295. Dr. Olson and Singh both described the hunting of fur seal as a seasonal Quinault activity, taking place regularly each year in the months of April and May when the animals could be encountered offshore on their annual migration to breeding grounds off the coast of Alaska. Ex. 213 at p. 49; Ex. 277 at p. 67. Dr. Lane was in accord. See Ex. 143.

7.2. Quinault traditionally fur sealed in an ocean canoe holding three men. According to Dr. Olson, the sealers cruised around the open ocean until a seal was sighted asleep in the sun. The sealers paddled quietly to move within harpoon range of the seal, whereupon the animal was struck with a harpoon, hauled toward the canoe, killed with a club, and hoisted aboard. Quinault preserved the meat and fat of the fur seal for consumption and used the skins for blankets and ropes. Ex. 213 at p. 49. These uses are consistent with treaty time subsistence purposes, taking place prior to trade with non-Indians. Tr. 3/16 at 122:16–123:5 (Boxburger). The Quinault sealing tradition mirrors that practiced by the Quileute and the Makah.

7.3. Beriah Brown’s 1895 article on Quinault marine mammal hunts shows that Quinault fur sealing continued in its traditional form through the late 1800s. Brown described implements of fur sealing similar to those described by Dr. Olson, including the “bone harpoon” and a specialized ocean-going sealing canoe fifteen or sixteen feet in length, and noted that the Quinault hunt fur seals in the open ocean, along with finback whales. Ex. 18 at pdf pp. 1–2. According to Brown, the Quinault “alone among the coast tribes...still follow the customs of their ancestors” in their pursuit of the seal, carrying out sealing voyages in canoes manned by three sealers and paddling as quietly as possible upon reaching the sealing grounds so as not to disturb the sleeping herds. Id. at p. 2. According to Brown, the sealers would regularly spend two days at sea during a hunt before returning to their village for several days’ rest. Id. Though written post-treaty, Brown’s account is indicative of both the important place of fur sealing in Quinault culture and the time depth of this customary practice.

7.4. The Quinault more likely than not ventured up to thirty miles offshore in pursuit of fur seals on a regular, seasonal basis at and before treaty times. Dr. Olson recorded that it was necessary for the Quinault to go ten to twenty-five miles offshore to hunt fur seals. Ex. 213 at p. 49; Ex. 211 at pdf p. 31. Dr. Olson contrasted fur seal hunting, which took place *1086 at distances far offshore, with the hunting of hair seals, which could be found on rocks close to shore. Id. While it is likely that the Quinault ventured even further post-treaty prompted by the demands of the commercial fur seal industry, the context of Dr. Olson’s descriptions makes clear that he was describing the Quinault’s pre-contact, traditional fur sealing activities. See Tr. 4/2 at pp. 80:1–81:12 (Renker). Beriah Brown’s article also places fur sealing thirty miles offshore, in the vicinity of the famous fishing bank off the coast from Shoalwater Bay. Ex. 18. Although Brown’s report was likely influenced by observations of post-treaty commercial fur sealing practices, he believed these practices to be consistent with pre-contact Quinault traditions.

7.5. These accounts of the distances at which the Quinault traditionally fur sealed place the sealers in the vicinity of optimal harvest. Fur seals are pelagic animals, spending their entire lives at sea other than their visit each year to their perennial breeding grounds. See Tr. 3/9 at 17:7–13. Current day tracking records and scientific studies demonstrate that, consistent with Dr. Olson’s ethnography, fur seals can be found in great abundance in April and May at the continental margin off the coast of Washington as they carry out their annual migration to breeding grounds, such as the Pribolof Islands in Alaska. See id. at 17–13, 44:10–22 (Trites). Consistent with Dr. Olson’s description of the Quinault fur sealing tradition, Dr. Trites explained that fur seal sleep during the day off the continental margin, making them vulnerable to hunters traveling quietly by canoe. Id. at p. 37:20–25; 60:1–61:13. Dr. Trites’ descriptions of current day fur seal behaviors were unrebutted, and the Court finds credible Dr. Trites’ testimony about the continuity of fur seal biology and behavior. As described in greater detail below, the behavior of fur seals at and before treaty-time is more likely than not consistent with their observed behavioral patterns today. These patterns support an inference that the Quinault were harvesting fur seals up to thirty miles off the coast of their territory at and before treaty-time.

B. Quileute Indian Tribe’s Western Boundary

1. Background on Traditional Quileute Economy

8.1. As with the Quinault, the Quileute Tribe was isolated before and in the decades immediately following the signing of the Treaty of Olympia. Prior to 1855, there were only four recorded interactions between the Quileute and non-Indians, or five if the 1775 Spanish encounter with either Quileute or Quinault whalers is included. The four encounters definitely attributed to the Quileute and their Hoh relatives include: (1) a report of a British expedition led by Charles Barkely, which visited the Washington coast in 1787 and was attacked by the Hoh at Hoh River, (2) an account of the 1782 Columbia expedition, which traded skins with the Quileute on its way north to Nootka Sound, (3) an account of the 1808 wreck of the Russian ship, the Sv. Nikolai, which wrecked off the coast of Quileute territory, and (4) the testimony of Mr. James, who was at La Push in 1854 for nine weeks assisting survivors of the wreck of the steamer Southerner and served as a witness in the Quileute’s land dispute with the settler Dan Pullen. Little was written by any of these visitors about Quileute culture or economy.

8.2. The United States government was almost entirely unaware of the presence of a tribe located between the Makah and the Quinault prior to the negotiation of the Treaty of Olympia. In 1854, George Gibbs wrote that “[s]till further north, and between the Kwinaitl [Quinault] and the Makahs, or Cape Flattery Indians, are other tribes whose names are still unknown, but *1087 who, by the vague rumors of those on the Sound, are both numerous and warlike.” Ex. B090.39. As set forth above, the Quileute were included in neither the Neah Bay nor Chehalis River negotiations. It was only in the course of these latter negotiations that the treaty commission became aware of the presence of the Quileute, whose population they estimated to number around 300 people. Ex. 65 at pdf pp. 23–24.

8.3. The Quileute remained isolated in the decades following the execution of the Treaty of Olympia, continuing to live in their traditional manner. See Tr. 3/12 at 50:17–51:4 (Boxburger). Annual reports of Indian agents evidence the difficulty in traveling to Quileute territory and the lack of non-Indian presence in the area. Superintendent C.H. Hale, for instance, reported to Washington on August 8, 1864 that the Quileute “know but little of the whites ... Their advantage consists in the fact of their village being surrounded for many miles with an almost impenetrable forest of gigantic growth. It is believed that no white man has ever been permitted to visit their village and its locality is only approximately known.” Ex 218 at p. 23. In 1877, an Indian agent similarly reported that the “Queets, Hohs and Quillehutes live at such a distance from the agency as to be entirely out of reach.” Ex. 218 at p. 33. In 1878, after oversight of the Quileute was transferred to the Neah Bay agency, Indian agent Charles Willoughby wrote that the “Quillehutes were unanimous in stating that they have only been once visited by an agent since the treaty was signed, and that visit they state was in the year 1862.” Ex. 350 at pp. 2–3. By 1882, Willoughby too admitted to not being able to visit the Quileute: “The Quillehute Indians are 30 miles from the Agency by land and 40 miles by water and so difficult of access that I cannot make frequent visits to them.” Ex. 218 at p. 33. The minimal familiarity of Indian agents with Quileute practices, coupled with the agency’s economic development orientation, render Indian agent reports of little utility in reconstructing customary Quileute fishing practices at treaty time.

8.4. During this post-treaty period, the U.S. government intended to move the Quileute together with the Quinault onto a new reservation established at the Quinault river. Several different Indian agents reported that the Quileute did not understand that by signing their treaty they would be forced to give up their homes. See, e.g., Ex. 7 at p. 335, Ex. B049 at pp. 14–15; Ex. B226 at pp. 5–6. In an 1879 council with the Quileute, Chief Howeattle, Head Chief of the Quileute, recalled that Colonel Simmons “told us when he gave us our papers that we were always to live on our land, that we were not to be removed to another place.” Ex. 281 at p. 161. The Quileute oral tradition likewise firmly roots the Quileute in their ancestral lands. Unlike neighboring tribes, the Quileute have no tradition of arriving on the Olympic Peninsula from other lands, instead asserting that they have always lived in this place. See Ex. 247 at p. 19. The Quileute remained on their land despite efforts to relocate them, and on February 19, 1889, the Quillayute Reservation was established by Executive Order at the Quileute coastal village, La Push. The first white settler to take up residency in Quileute territory was a schoolteacher, sent to oversee the Quileute when the first school was established at La Push in 1883 and who set about attempting to assimilate the Indians by assigning them colonial names. Ex. 218 at p. 25.

8.5. Into the 1890s, the Quileute nonetheless remained unfamiliar with white culture and notions of property. Evidencing the tribe’s indigenous worldview, the settler Karl Olof Erickson remarked on his meeting with the Quileute that “the leader *1088 of the group[ ] made an address and pointed to the woods, the ocean, and the sky.” Ex. 145 at p. 85. Erickson presented the assembled Indians with his receipt for money paid at the U.S. Land Office in Seattle for his land claim, but this symbol of property ownership “did not mean anything” to the Quileute. Id. Tensions related to these differing notions of ownership arose when the settler Dan Pullen claimed land at La Push around 1883 and attempted to have the Quileute removed form the area. Several months after the Quillayute Reservation was established, Pullen burned the La Push village to the ground when its residents were away working in the Puget Sound hop fields. See Ex. B063.15. As a result, the Quileute suffered a devastating loss of most of their aboriginal artifacts, including their whaling and fur sealing implements and canoes. See Tr. 3/12 at pp. 26:15–28:8 (Boxburger); Ex. B63 at pdf. p. 15.

8.6. Owing to their relative isolation and minimal contact with Indian agents and white settlers, the Quileute maintained their traditional practices through the early 1900s. The noted anthropologist Dr. Leo Frachtenberg, who studied the Quileute from 1915–16, reported that his “investigation was facilitated by the fact that the Quileute Indians, numbering approximately 300 individuals, live together in a single village and still cling tenaciously to their native language, and to their former customs and traditions.... [Their] condition seems to be due to their complete isolation from the other tribes and from the white people, and to their persistence in adhering to the former customs and beliefs.” Ex. B096 at pp. 111, 113.

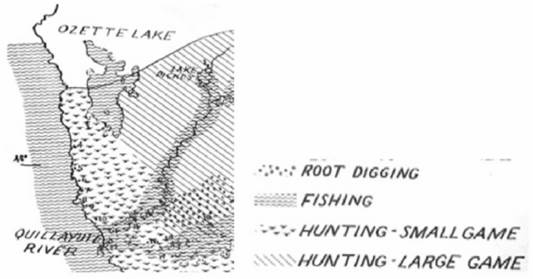

8.7. Judge Boldt recognized that “[f]ishing is basic to the economic survival of the Quileute,” FF 110, and it continues to be depended upon as a major source of income for the tribe. See Tr. 3/2 at 158:3–159:21. As it did for the Quinault, fishing constituted the principle economic and subsistence activity of the Quileute at and before treaty time. See FF 104, 105. Like the Quinault, the Quileute were favorably situated to harvest trout and steelhead, which were “taken in their long and extensive river systems.” FF 104. The Quileute were also able to travel into the upland foothills to hunt by following their river system in canoes. Id. Individual Quileute families asserted ownership of river fishing grounds. FF 106; Ex. 58a at pdf p. 120. Pre-treaty Quileute villages were located where the conditions of the rivers were optimal for catching fish, with each village obtaining its principal supply of fish from a sophisticated fishtrap located nearby. FF at 109. Recognizing the tribe’s customary use of rivers and lakes for their subsistence supply, Judge Boldt included a number of inland water bodies in his determination of the Quileute’s case area U & A, including: “the Hoh River from the mouth to its uppermost reaches, its tributary creeks, the Quileute River and its tributary creeks, Dickey River, Soleduck River, Bogachiel River, Calawah River, Lake Dickey, Pleasant Lake, [and] Lake Ozette.” FF 107.

8.8. At the same time, ocean fishing undoubtedly played a significant role in the traditional Quileute economy, culture, and identity. Judge Boldt recognized the importance of oceanic resources to the Quileute in including “adjacent tidewater and saltwater areas” in their U & A. FF 108. In furtherance of this determination, Judge Boldt found that before and at treaty time, the Quileute harvested diverse resources in the Pacific Ocean, including “smelt, bass, puggy, codfish, halibut, flatfish, bullheads, devilfish, shark, herring, sardines, sturgeons, seal, sea lion, porpoise, and whale.” Id. As they did with respect to their inland lakes, the Quileute viewed the waters of the ocean as common property. FF 106; Ex. 65(a) at pdf p. 120.

*1089 8.9. Early settlers and visitors to Quileute territory make mention of Quileute use of ocean resources, as does every ethnographer to have done work among the Quileute. The anthropologist Ram Raj Prasad Singh, who did field work with the Quileute in the 1950s, noted the unusual diversity of the tribe’s economic resource base. Singh noted that, unique among the three Olympic coast tribes, the Quileute exploited all three of the economic resource areas available on the Peninsula: the deep sea economy, the river and coastal economy, and the inland economy. Ex. 277 at p. 4 (noting that “the Makah had primarily a deep sea economy; the Quinault, river, coastal, and inland; the Quileute, all three”). Singh explained that the Quileute were situated in a unique geographic zone where none of the economic resource areas was sufficient on its own to provide for adequate subsistence. Id. at p. 127.

8.10. The desire for dietary variety and the wide range of uses that the tribe found for the varied resources they exploited served as additional motivations for the Quileute to utilize a broad resource base. As one of Singh’s Quileute informants related, “[t]he Indians did not want all fish or all whale but liked to get some of everything which they wanted to eat.” Ex. 277 at p. 73. According to Singh, “[c]hoice in production gave the Indians a freedom unknown to most hunting tribes the world over.” Id. Specialization in occupations and in the tools and technologies for extracting resources in their different environmental zones abetted the Quileute’s exploitation of a diverse range of resources. See Tr. 3/12 at pp. 76:26–77:11 (Boxburger); Ex. 277 at p. 81. The Quileute, for instance, had specialized technology for seafaring and harvesting different ocean resources, including four different canoes and four specialized hooks for ocean hook and line fisheries. See Ex. B350.13; Ex. B310; Tr. 3/30 at pp. 47:21–48:5 (Thompson). Intra-tribal trade networks further spurred economic specialization. Members of both the Quileute and the Quinault tribes who lived on coastal settlements harvested aquatic resources for intra-tribal trade with upriver tribal members in exchange for meats and furs. See Ex. 277 at p. 81.

8.11. Anthropologists who studied the traditional Quileute economy noted a startling variety of ocean resources harvested by the tribe. These resources included a wide range of finfish (flounder, sole, rock fish, bullheads, suckers, skate, surgeon, smelt, sardines, herring, dog fish, sea bass, cod, salmon, halibut, and others), sea mammals (hair seal, sea lion, sea otter, porpoise, dolphin, fur seal, gray whale, humpback whale, killer whale, fin back whale, blue whale, and sperm whale), and shellfish (crab, clams, octopus, mussels, barnacles, squid, rock oysters, chiton, sea urchin, sea anemone, and goose neck barnacle). See, e.g., Ex. 58(c) at pdf pp. 40–48, 61; Ex. 247 at pp. 14–16. According to Singh, marine resources were customarily harvested by the tribe during the months of April through August, when the tribe would harvest hair seal, fur seal, whale, sea lion, and smelt, and engage in “deep sea fishing.” Ex. 277 at p. 65. Dr. Lane too reported that the Quileute “pursued whales, seals, sea-lion, porpoise and fished for halibut, cod, bass, salmon and other species in the marine waters off the west coast of the Olympic Peninsula.” Ex. B349.2.

8.12. Quileute Indians who addressed government officials in the post-treaty era consistently attested to the tribe’s customary subsistence harvest of ocean resources. Stanley Gray, a Quileute born in 1864, emphasized the importance of ocean resources in traditional Quileute culture and economy in his testimony in United States v. Moore, a case concerning the intended *1090 scope of the Quillayute Reservation. Gray testified that the Quileute hunted whale and seal in the Pacific Ocean “in the early days.” He further testified that the Quileute “fished for halibut, ling cod, and whale” in the Pacific Ocean “continuously” during his lifetime. Ex. 178 at pp. 346–49. Similarly, when Edward Swindell, an attorney for the Department of the Interior, visited various tribes to identify their subsistence activities, several Quileute described the importance of ocean resources and intra-tribal trade between coastal and inland villages. Sextas Ward, a Quileute born in 1856, explained that “the Indians who lived in the villages along the various streams were able to catch much more salmon that those who lived along the ocean, whereas those along the ocean could obtain seal, whale and smelt; that as a result of this they were accustomed to trade amongst themselves so that they could have all kinds of fish and sea food for their daily subsistence.” Ex. 293 at p. 221. Similarly, Benjamin Sailto, a Quileute born in 1853, told Mr. Swindell that the Indians living at the ocean would “catch whales and seals in the ocean” and that the people who lived upriver “would visit the Indians at other places or else come down to the main village at La Push for festivities and to obtain a supply of the different kinds of fish food which they could not obtain at their own fishing places.” Id. at p. 225.

8.13. Like the Quinault, the Quileute possessed navigational skills, knowledge, and technologies to travel extensively on the open ocean, reaching distances out of sight of land. Dr. Lane opined that the “Quileute and Hoh Indians at treaty times were known for their seamanship.” Ex. B349.2. Like the Quinault, the Quileute propelled their ocean canoes by means of both paddles and sails. Ex. 58(a) at pdf p. 160. Frachtenberg specifically contrasted the traditional Quileute ocean-going equipment, including large paddles and a single sail set upon poles in the bow of the canoe, with the oars and canvass sails used in the early 1900s. Id. According to Frachtenberg, the Quileute traditionally used their canoes to travel 20–30 miles westward, as far south as Tahola (50 miles south of La Push), and as far north as Neah Bay (45 miles from La Push). Id.

8.14. Various historical and anthropological accounts relate Quileute knowledge of weather forecasting and the sophisticated navigational techniques the Quileute employed when voyaging offshore. Chris Morgenroth, who settled on the Bogachiel River in the 1880s, described in his autobiography his near deadly attempt to reach Neah Bay in a whaling canoe launched from La Push and crewed solely by him and other white settlers. Upon leaving La Push, Morgenroth was warned by Chief Howeattle to “Look out for the East wind!,” a warning that Morgenroth and his crew regretfully ignored. Ex. 180 at pp. 62–65. Both the anthropologist Professor Jay Powell, who lived with the Quileute for four decades, and the anthropologist Richard Daugherty commented on the traditional weather forecasting techniques used by the Quileute. See Ex. 220 at pp. 9, 111 (discussing the ability to tell which way the wind is coming from by the roar of the ocean and to predict weather by the appearance of fog and clouds); Ex. B345.14 (noting “weather forecasting” by Quileute sealers). Various oral traditions reflect Quileute knowledge of the stars used for navigation, as well as Quileute use of the sun’s position as a navigational tool while at sea. See, e.g, Ex. B333 at pp. 51–56 (myths about the origin of the stars and constellations), 71–74 (oral tradition that whaling season begins when the sun goes straight across the ocean to the west).

8.15. The Quileute language reflects the tribe’s oceanic orientation. Professor Powell’s dictionary of the Quileute language records over ten distinct words for *1091 canoe, including separate words for “sealing canoe,” “fur sealing canoe,” “whaling canoe,” and canoes of various sizes. Ex. 225 at pp. 44–45. Quileute words exist for a wide range of aquatic animals associated with the tribe’s pre-treaty subsistence practices. The Quileute also possess distinct words associated with wide-ranging ocean traveling, including words meaning “to go out on the ocean,” “at sea,” “sea, blue water,” and “sea, out in the ocean, west.” Id. at p. 194; see also Ex. 233 at p. 159. Further words exist for a variety of sails used for traditional ocean travel and whaling purposes, as well as for stars associated with navigation. See Ex. 233 at pp. 154, 177.

2. Quileute Offshore Fishing

9.1. The archaeological and ethnographic evidence show that the Quileute engaged in offshore fisheries on a regular, seasonal basis for a range of oceanic finfish at and before treaty time.

9.2. Fish bone data assemblages from middens associated with aboriginal Quileute occupancy evidence a community continuously engaged in harvesting finfish from the Pacific Ocean. Quantified faunal data is available for four sites associated with the Quileute: Cedar Creek (representing late prehistoric occupation), Cape Johnson (representing occupancy from 700 to 1100 years before present), La Push (dating 600 to roughly 900 years ago), and Strawberry Point (representing occupancy between 1650 and 1950). The species compositions of the bone assemblages at these sites are very similar to those found at the ten sites associated with Makah occupancy, for whom a forty mile offshore U & A has been determined by this Court. The three most prevalent fish at each of the Quileute sites are: (1) greenling, red Irish lord, and lingcod (Cedar Creek), (2) greenling, red Irish lord, and cabezon (Cape Johnson), (3) rockfish, salmon, and flatfish (La Push), and (4) perch, greenling, and lingcod (Strawberry Point). The top species compositions at Makah sites are analogous, with flatfish, rockfish, greenling, salmon, and lingcod typically found among the most prevalent three or four species. See Tr. 4/6, 163:11–165:11 (Wessen). Based on these comparisons, the archaeologist Dr. Wessen, whose testimony the Court finds credible, testified that “there are broad similarities among all of these sites in fish bones.” Id. at 164:8–9.

9.3. The types of species found at the Quileute sites suggest a strong oceanic orientation. Species like greenling, perch, lingcod, and sculpins (including red Irish lord and cabezon) would have been available to the tribe five to ten miles offshore, though they can also be found both nearer to shore and in deeper waters. See Tr. 3/11 at pp. 181–84 (Gunderson). Others, like rockfish, are most abundant in habitats deeper than 50 fathoms. Id. at 161:21–162:1. Hake, representing 1.4% of fish bone specimens at the Cape Johnson sites, and halibut, representing 2.5% of fish bone specimens at the La Push site, are strongly indicative of offshore harvest. Hake are a fish associated with deeper waters, see Tr. 3/11 at 15–16 (Schalk), though they too range from nearshore to distances beyond the 100–fathom line. See Tr. 4/3 at 109–109 (Joner). Dr. Gunderson, whose testimony the Court finds credible, testified that halibut are most common at depths from 30 to 230 fathoms, although they can be found in smaller quantities in nearshore waters as well. See Tr. 3/11 at 169:19–20 (Gunderson); see also Tr. 3/11 at 5:12–25 (Schalk).

9.4. The low percentage of halibut at Quileute sites may not accurately reflect its importance in the Quileute economy. In particular, evidence suggests that halibut may be underrepresented at archaeological sites because it was often filleted on the beach rather than at village sites. See Tr. *1092 4/6 at 174:2–23 (Wessen). Limited archaeological excavations at three additional Quileute sites—the Toleak Point site and two sites on Destruction Island (located 4 miles offshore)—provide further evidence of Quileute engagement in halibut fishing. Tentative identifications of fish bones at the Destruction Island sites indicate the probable presence of halibut, Ex. 267 at p. 3, and hooks and grooved stone sinkers associated with halibut fishing have been found at the Toleak Point site. See 3/10 at pp. 142:1–145:2 (Schalk). Halibut is also present at high frequencies (26% of fish bones) at an additional site at Sand Point located on the Washington Coast west of the northern portion of Lake Ozette and abandoned approximately 1,600 years ago. The Sand Point site may be reflective of either Makah, Ozette, or Quileute activity. See Tr 4/6 at pp. 42–43 (Wessen).

9.5. The presence of offshore birds in the middens, accounting for 31% of bird bones at La Push, provides additional circumstantial evidence of offshore fishing activities. See Tr. 3/10 at 162:4–163:5 (Schalk). These birds were likely taken incidental to offshore fishing and marine mammal hunting. Ex. 338 at pp. 32–34.

9.6. Ethnographic and historical evidence is broadly consistent with the archaeological evidence of regular and customary ocean finfish harvest by the Quileute at and before treaty time. James Swan, who traveled to La Push in 1861 on a trading vessel and remained for four days, later informed the U.S. Fish Commission that the Indians south of Cape Flattery subsisted principally on “rock cod, surf smelt, tomcod, salmon, etc.” Ex. 318 at p. 66 (1888 U.S. Fish Commission Bulletin). The importance of salmon and smelt to the Quileute is corroborated by Swan’s descriptions of first salmon and first smelt ceremonies. See Ex. 287 at p. 45. While Swan did not believe that the Quileute were harvesting halibut, the archaeological and ethnographic record proves him mistaken on this point. For instance, multiple sources document traditional Quileute fishing for halibut at halibut banks, where specialized U-shaped hooks similar to those used by the Makah were employed to catch the fish. See Ex. 248 at p. 447, Ex. B346.40. Frachtenberg too discussed specialized gear and fishing techniques used by the tribe for offshore harvest of halibut, cod, bass, and other species. Ex. 56(c) at pdf pp. 68–76. According to Frachtenberg, the Quileute caught fish in the ocean using five different types of hooks as well as lines made of dried kelp. See Ex. 58(a) at pdf p. 128. Women and men would go out together on fishing trips in the ocean, during which specialized ocean canoes somewhat smaller than sealing canoes were used. Ex. 56(c) at pdf p. 69. The Quileute also took salmon by trolling in the open ocean and took herring from their canoes by means of a herring rake. See Ex. 293 at p. 184; Ex. 37a at p. 143; Ex. 58(a) at pdf p. 131.

9.7. While it is not possible to document the precise outer bounds of traditional Quileute finfish harvest in the Pacific Ocean, evidence suggests that the Quileute were more likely than not harvesting finfish up to twenty miles offshore on a regular and customary basis. According to Frachtenberg, halibut was harvested within two miles of shore, cod taken along rock and reefs, and other fish caught under rocks in rough weather with a kelp line. Ex. 56(a) at pdf at pp. 129–133. Other reliable accounts, however, place Quileute fishing further offshore. Singh, for instance, reported that the coastal Indians, including the Quileute and Hoh, harvested bass six miles offshore and fished at halibut beds eight to twelve miles offshore. Ex. 277 at pp. 19, 32. Quileute tribal member Bill Hudson, born 1881, informed Richard Daugherty that the Quileute fished for halibut in depths of 50 to 60 fathoms using kelp lines *1093 in the traditional, pre-contact style. Ex. B346.40 at pdf p. 340; Tr. 3/2 at 116:18–119:9 (Boxburger). Fishing at a depth of 50–60 fathoms would place the Quileute approximately twenty miles offshore of La Push and at areas of peak abundance of halibut during the summer season. Id.; Tr. 3/11 at 171:5–9, 174:12–25 (Gunderson). This is a distance to which Frachtenberg reported that the Quileute were accustomed to travel westward in their ocean canoes. Ex. 56(a) at pdf pp. 162–63.