Because of their close connection to the natural world, Indigenous Peoples are among those most affected by climate change, despite their negligible carbon footprint. Recognizing climate change’s threat to homelands and ways of life, the National Congress of American Indians and the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) have joined the community of nations in climate change negotiations at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). NARF participates on behalf of its client NCAI as part of the International Indigenous Peoples Forum on Climate Change.

In December 2015, at the COP21 (Conference of the Parties 21, the main decision-making body of the UNFCCC), the 195 participating parties agreed to the first ever universally binding accord on climate change, the Paris Agreement.

In preparation for Paris, the Norwegian government donated funding to enable greater Indigenous participation in the process. Indigenous Peoples consulataions took place in all seven regions of the world. Dozens of Indigenous representatives from around the world came to Paris, including numerous representatives from United States Tribal Nations. This participation was crucial in lobbying for language concerning Indigenous issues in the Agreement.

The Indigenous caucus had several issues which it pushed for inclusion in the Agreement. One of the most important was to get a provision in the operative section of the Agreement recognizing that climate change policies and procedures had to respect, protect, promote, and fulfill the rights of Indigenous Peoples within a broad human rights framework. The effort resulted in a provision which states:

Acknowledging that climate change is a common concern of humankind, Parties should, when taking action to address climate change, respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights, the right to health, the rights of Indigenous Peoples, local communities, migrants, children, persons with disabilities and people in vulnerable situations and the rights to development, as well as gender equality, empowerment of women and intergenerational equity

A second issue of importance to the Indigenous caucus was the recognition of the importance of indigenous Peoples’ knowledge in relation to climate change. To that end, the Paris Decision established a Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform to provide an opening for traditional knowledge to influence climate policy at local, regional, and international levels.

While the platform was established at COP 21, the implementation has been incremental. The COP 24 (2018) established a Facilitative Working Group to develop a work plan for the platform. The working group has 14 representatives: seven country representatives and seven Indigenous representatives appointed by Indigenous Peoples (one from each of the seven regions of the world). This representation of Indigenous Peoples is unprecedented, marking the first time that Indigenous representatives (chosen by Indigenous Peoples) will participate on an equal basis with states within a United Nations body.

Ultimately, the platform will institutionalize dialogue between states and Indigenous Peoples, foster Indigenous participation in the discussions on environmental policy, and encourage a holistic response to climate change. According to a statement from the UN:

Indigenous Peoples constitute less than five percent of the world’s population, but they safeguard 80 percent of the world’s biodiversity. The global response to climate change requires applying all of the best knowledge available, including the perspectives of Indigenous Peoples and local communities at the front lines of climate change. Indigenous Peoples are not only among the most vulnerable to its impacts, but they also hold many of the solutions to adapting to climate change.

The working group met in June 2019 and prepared a two-year work plan for the LCIPP, which was taken to COP 25 and approved in December 2019.

Because of the pandemic, COP 26 was not held in 2020. Because of the continued disruption from the pandemic, the third and fourth meetings of the FWG occurred virtually in October and December 2020. Updates were given on implementation of the work plan. Key parts of the plan, involving face to face meetings were not possible, and it was made clear that the knowledge holders would not go forward in a virtual format. Therefore, that part of the work plan were postponed. However, a series of educational webinars on traditional knowledge were held and much progress was made in collecting information about interface with the LCIPP and other constituted bodies in the UN and with bodies outside the UN.

The fifth meeting of the working group was held virtually in June 2021 and a three-year plan for the LCIPP was developed for consideration at COP 26.The sixth meeting of the FWG preceded the COP 26 (2021) meeting. This was a crucial meeting for completing consideration of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement and for considering the draft three-year plan of the working group. The United States was represented by Secretary Haaland. President Sharp of NCAI was the first Tribal leader to be credentialed by and join the US delegation. Other moments from COP 26:

- There was a historic gathering of Indigenous traditional knowledge holders. Knowledge holders came from all seven social-cultural regions of the world. It represents a further step in the recognition of the importance of traditional knowledge to addressing climate change. In addition, the draft

working group workplan was approved. - One of the key goals of the COP was to put the world on target to keep global warming under 1.5 C. In that regard, it cannot be called a success. We are headed to 2.4 C based on current commitments.

- Another goal of COP 26 was to finish the rulebook dealing with Article 6 – market and non-market mechanisms. The Indigenous caucus proposed language, but failed to make any progress.

- There was an announcement of an historic $1.7 billion commitment from philanthropy and governments for Indigenous-led solutions for forests and lands

protections with a promise to prioritize the inclusion of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the design and implementation of programs from 2021-2025.

During various 2022 meetings, a broad range of subjects was discussed, ranging from the Global Stock take which will assess the state of implementation of the Paris Agreement, land rights defenders, to the recent reports of the three working groups (WG) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Of particular note was WG III’s mention of traditional knowledge and its acknowledgment of the role colonization has played and continued to play in climate change. The point was made that the Paris Agreement itself is touched by colonization with its constant reference to “best available science” rather than “best available knowledge”.

As to Loss and Damage, the Indigenous caucus stressed the issue of non-economic loss such as loss of livelihoods from even well-intentioned efforts such as

development of “green” energy projects which interfere with Indigenous ways of living. As to Article 6.4, a Supervisory Body was charged with developing rules and regulations governing the operation of the mechanism, and ensuring adherence to human rights and the rights of Indigenous Peoples. The rules were to be developed prior to COP 27, but the task proved too much and work continued after COP 27.

The eighth meeting of the Facilitative Working Group of the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform took place preceding the start of COP 27. The main outcome of COP 27 was the creation of a loss and damage mechanism, insisted upon by the developing countries. Loss and damage refers to the damage that is unavoidable even if adaptation measures have been taken.

The 58th session of the subsidiary bodies of the UNFCCC took place in Bonn in June 2023. In addition, the 9th meeting of the Facilitative Workgroup of the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform took place preceding those meetings. This unfortunately, due to circumstances beyond control was the first time since 2009 that no one from NARF or NCAI was able to attend.

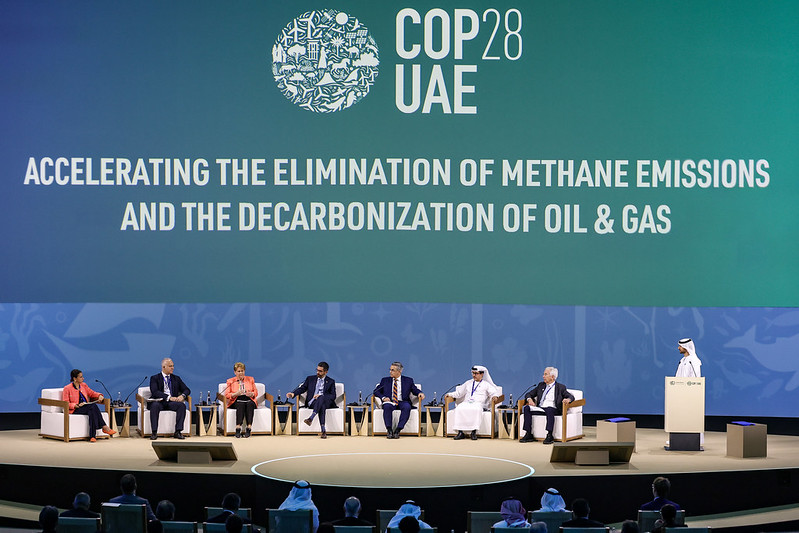

NARF and NCAI did attend COP 28 in November 2023 in Dubai. A big issue at COP 28 was the Global Stock take (assessing where we are in meeting the goals of the Paris Accord). It was notable for the first time mentioning a transition away from fossil fuels in the energy sector. A Loss and Damage mechanism (the need for the developed world to address the need of the developing world for assistance in dealing with Loss and Damage caused largely by emissions from the developed countries) was established on the first day of the COP. Initial pledges of 700+ million were made, far below the amount needed to address the loss and damage throughout the world. A matter to be worked on is to ensure active observer participation by Indigenous Peoples and direct access by them.

Along with NCAI and members of the Indigenous caucus, we submitted extensive comments to the Supervisory Body in February 2024 outlining the inadequacies of the grievance and appeals processes. They are woefully inadequate to deal with issues such as title to Indigenous lands. Nevertheless, the appeals and grievance procedures were adopted with much fanfare. It is true that it is an improvement to even have such processes, as they did not exist under the Kyoto Protocol, but unfortunately they are not what was hoped for.

NARF, on behalf of NCAI, attended the intersessional meetings in May/June 2024, which included a meeting of the working group. Notable was the recommendation of SBSTA to have the COP approve the three year plan for 2025-2027. In addition, we held bilateral talks with Canada, Australia, and the United States stressing the importance of Indigenous rights in all climate action. With the United States we stressed the importance of the Sustainable Development Tool which

is used to determine whether projects under Article 6.4 are approved. This is especially important given the inadequacies of the appeals and grievance process. A good number of our suggestions have been incorporated into the latest draft of the Sustainable Development Tool and we are hopeful that they will remain in at the next Supervisory Body session in July when the tool is likely to be approved.

In addition, we are monitoring the Loss and Damages Fund which was approved at COP 28. Important issues to be addressed are access to funding by Indigenous Peoples from all seven socio-cultural regions, roles as active observers, averting non-economic losses such as those to sacred sites, and honoring the rights of Indigenous Peoples. Finally, the caucus is focused on Just Transition which some want to limit to seeing that those who lose jobs in the

transition to the “green” economy get new jobs. The caucus stresses that just transition must include the rights of Indigenous Peoples to their lands, territories, and resources which are threatened by mining of new minerals such as lithium for the “green” economy. During side events at COP 28, the Indigenous Caucus highlighted the growing danger of the transition to new energy requiring the mining of minerals such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel, all of which poses grave dangers to Indigenous rights. A summit on this issue was held in October of 2024, for Indigenous Peoples from all 7 regions of the world.

In October 2024, the Supervisory Body for the Article 6.4 Mechanism (“SB”) adopted the final text of the Sustainable Development Tool (“SDT”), essentially regulations operationalizing Article 6.4, designed to protect environmental and human rights, including the rights of Indigenous Peoples. The SDT provisions require those participating in the Paris Agreement’s Article 6.4 Crediting Mechanism to identify, evaluate, avoid, minimize and mitigate potential risks and impacts associated with projects over the course of their lifetime, including risks and impacts to Indigenous Peoples, their rights and communities.

Throughout 2024, NARF, on behalf of NCAI, assisted the Indigenous caucus in developing and drafting comments and proposed-text recommendations for evolving versions of this SDT. The final text adopted by the SB includes much of the language we proposed and advocated for, including requirements that project participants must adhere to the principle of “free, prior, and informed consent” with respect to Indigenous Peoples. With regard to protecting the rights of Indigenous Peoples, the final text of the SDT, while not perfect, benefitted from the involvement of NARF/NCAI

and the recurrent submissions of the Indigenous caucus.

In October, the Supervisory Body for Article 6.4 also adopted standards for removals and methodologies. Unlike the SDT, these standards must be approved at COP 29. NCAI and NARF will continue to advocate for improvements to these standards.

More Cases