It is essential that Indigenous voices be heard on the international stage. Particularly for topics, like climate change, that disproportionately affect Indigenous communities. At issue is how Indigenous Peoples can best participate in a United Nations structure that was not set up to include them. NARF has represented the National Congress of American Indians at the United Nations since 1999.

Background:

The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

After 30 years of worldwide Indigenous efforts, in September 2007, the United Nations General Assembly overwhelmingly adopted the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (the Declaration). The Declaration recognizes that Indigenous Peoples have important collective human rights in a multitude of areas, including self-determination, spirituality, lands, territories, and natural resources. It also sets out minimum standards for the treatment of Indigenous Peoples and can serve as the basis for the development of customary international law.

The 2007 vote was tallied at 143 in favor of the Declaration, four opposed, and eleven abstaining. The votes in opposition were Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. In 2009 Australia and New Zealand reversed their positions. Canada endorsed the Declaration in November 2010 and on December 16, 2010, President Obama made the historic announcement that the U.S. was reversing its negative vote.

Implementing the Declaration

Tribal leaders, Indian law practitioners, and scholars began to develop recommendations on the implementation of the Declaration in the United States. In June 2011, the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs held a hearing on implementing the Declaration. NARF submitted written testimony on behalf of its client, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), to identify what actions were needed to make U.S. law conform to the standards set by the Declaration. The testimony addressed issues such as self-determination, lands and territories, and informed consent during legislative or regulatory decision making. The testimony is available on the Senate committee’s website.

In the May 2013 meeting of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in New York City, more than 72 tribal nations and ten Indian and Native Hawaiian organizations, including NCAI and NARF, called on the United Nations (UN) to become more inclusive of Indigenous governments. The joint statement recommended three focus areas:

- Establish a body at the UN to monitor implementation of the Declaration.

- Create a permanent, dignified, and appropriate status for Indigenous Peoples at the UN

- Address violence against Indigenous women.

In June 2013, Indigenous Peoples from around the world held a meeting in Alta, Norway. This meeting produced recommendations for the implementation of the Declaration, which were used to lobby states in advance of the 2014 World Conference on Indigenous People. The Alta recommendations can be found at the United Nations website. The UN General Assembly subsequently adopted a document that addressed all of the elements proposed by the Indigenous organizations and tribal governments:

- Establish a body at the UN to monitor implementation of the Declaration.

- Create a permanent, dignified, and appropriate status for Indigenous Peoples at the UN.

- Address violence against Indigenous women.

- Protect sacred places.

In 2019, NARF partnered with the University of Colorado Law School to create The Implementation Project: Achieving the Aims of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Improving Indigenous Participation at the UN

A number of meetings of world Indigenous Peoples were held throughout 2015 and 2016. These meetings focused on the Alta recommendation, to establish a body at the UN to monitor implementation of the Declaration. The body was called the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP) and the meetings focused on how to best enable it to review states’ compliance with the Declaration. Ultimately, in September 2016, the United Nations passed a resolution that expanded and improved the EMRIP mandate by adding members, meetings, autonomy, and responsiveness for the group. The resolution A/HRC/33/L.25 can be found at the United Nations website.

Since that time, the world Indigenous community is focused on the second recommendation and improving participation of Indigenous institutions at the United Nations. Historically, Indigenous Peoples have had to appear in most United Nation bodies as non-governmental organizations, which is unacceptable to Indigenous Peoples’ governments and representative institutions. Indigenous representatives met consulted with member states in 2016 and 2017. The UN General Assembly committed in September 2017 to continue to consider the issue for the next five sessions, and directed that additional regional consultations take place and that a report be compiled. Submissions by Indigenous Peoples and member states can be found at https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/reports-by-members-of-the-permanent-forum.html.

Participation in the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues: Traditional Knowledge

The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) is a high- level advisory body to the Economic and Social Council. The Forum was established to deal with Indigenous issues related to economic and social development, culture, the environment, education, health and human rights.

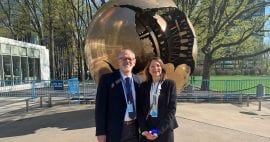

On April 23, 2019, NARF Staff Attorneys Sue Noe and Kim Gottschalk represented the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) at the UNPFII Eighteenth Session, which focused on traditional knowledge. While there, they submitted a statement on the importance of international attention to traditional knowledge:

It is crucial to have this discussion on traditional knowledge because of the important contributions traditional knowledge makes to the world, because of the vulnerability of traditional knowledge to misappropriation, and because of the undermining of the traditional context in which such knowledge is generated and transmitted.

The statement goes on to makes recommendations for the participation of Indigenous representatives and protection of traditional knowledge.

(See also NARF’s work at the World Intellectual Property Organization dealing with traditional knowledge.)

More Cases