by Sonia Tamez

It’s been eight months since I visited the Bears Ears area, and I am still dreaming of its beauty, but I am also increasingly sleepless about its future. I drove from California, past cities, rural communities, ranches, and farms into the long vistas of the Colorado Plateau in Utah where the Bears Ears cultural landscape is located. During my visit, I found out about the Bears Ears National Monument designated by President Obama and the current assaults on the monument. I walked, offered tribute, painted, and I also vowed to resist the shrinking of Bears Ears when I returned home.

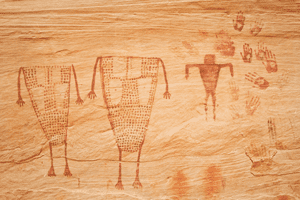

I learned that the Bears Ears area is sacred to at least five Tribes (Hopi, Navajo, Uintah and Ouray Ute, Ute Mountain Ute and the Pueblo of Zuni). It is also culturally and scientifically significant with hundreds of thousands of traditional cultural landscapes, sacred sites, and archaeological and paleontological resources. Tribes still gather medicinal plants and herbs, obtain food and fuel, and conduct ceremonies. Traditional practitioners still visit to connect with their ancestors.

I am still in awe of the beauty of the Bears Ears area, but I am anxious that this is a landscape at risk. The National Trust for Historic Preservation, in partnership with the All Pueblo Council of Governors, Friends of Cedar Mesa, and others, included 1.9 million acres of the Bears Ears cultural landscape in its National Treasures Program in 2014. The Trust also added the Bears Ears cultural landscape to its Most Endangered Historic Places in America list in 2016, citing a lack of staff and funding, destruction from looting, mismanaged recreation use, and threats from energy development.

The history of the creation and dismantling of the Bears Ears Monument is chronicled in detail on many websites, media outlets, and blog posts. However, I want to emphasize certain critical points here about collaboration with Tribes, prioritization of protection for the monument, and what we can do.

In 2010, tribes along with the Utah Dine’ Bike’yah nonprofit sought to safeguard the Bears Ears region. Support for their proposed protection of a cultural landscape grew. Over the years, the Bears Ears Intertribal Coalition and others worked together to protect the Bears Ears cultural landscape. A public comment process was also undertaken.

President Obama established the 1.35 million acres Bears Ears Monument in December of 2016. The original monument was envisioned as 1.9 million acres, but in a compromise, its size was reduced.

The monument declaration described a collaborative process between two federal agencies (the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Forest Service (FS)) and the five Tribes through the Bears Ears Commission, to include one elected officer from each of the Tribes. It was designed “so that it may effectively partner with the Federal agencies by making continuing contributions to inform decisions regarding the management of the monument”. An advisory committee was also established to include various stakeholders. The Bears Ears Monument was heralded as the first successful multi-tribe-led effort for a national monument in the history of the United States.

Sadly, on December 4, 2017, after a perfunctory review, the Trump administration slashed the Bears Ears Monument by approximately 1,150,860 acres. The current administration replaced it with two much-reduced, discontinuous areas: the Shash Ja’a and Indian Creek units totaling only approximately 201,876 acres. The framework for tribal collaboration established earlier also was undermined.

An expedited new land management plan, led by BLM with the FS, is being produced for the much smaller monument. My initial impression is that the draft plan alternatives, management options, and priorities were not collaboratively developed with Tribes. Tribal collaboration in developing the draft plan is critical for an informed decision of this magnitude or subsequent management.

There is mention of site probabilities, but are all cultural resources of interest to Tribes and traditional practitioners included? On-going research projects and tribal interviews are mentioned, but it is not clear if the results informed the draft plan or even if they will be available to be considered in the final plan and the Record of Decision. The draft plan overall provides a lot of discretion for future management decisions on some of the most impactful activities on cultural resources from earth disturbing activities.

There is mention in the draft plan of collaboration with Tribes as a goal, but the mechanisms and framework to do so are not included. The current administration declared that the monument commission shall be known as the Shash Ja’a Commission, restricted to the Shash Ja’a unit, and must include an elected San Juan County Commission officer. There is no mention of a tribal commission for Indian Creek.

There is also a new Bears Ears National Monument Advisory Committee. However, although there are 5 sovereign Tribes, only 2 representatives of “tribal interests” are allowed on the 15-person committee. The new commission and advisory committee charter and membership raise a lot of questions, but even if they were effective in helping protect the new monument, the draft plan appears to have preceded them and did not benefit from their contributions. This draft plan process and schedule do not meet the need for collaboration with Tribes required for this special place.

There is no new draft plan for the remainder of the Bears Ears cultural landscape outside the new designation, and its protection is not clear. The original Bears Ears Monument designation by President Obama removed the 1.35 million acres from mineral entry. The current President’s declaration for the reduced monument states that

“…the areas excluded from the monument reservation shall be open to:

(1) entry, location, sale, or other disposition under the public land laws and laws applicable the US Forest Service;

(2) disposition under all laws relating to mineral and geothermal leasing; and

(3) location, entry and patent under the mining laws.”

Instead of an updated management plan that the Indian Creek and Shash Ja’a units will receive, only the old 2008 BLM Land Management Plan governs the majority of the excluded portions. This 2008 Plan states that “except for Congressional withdrawals, public lands shall remain open and available for mineral exploration and development unless withdrawal or other administrative actions are clearly justified in the national interest…” (emphasis added).

A cursory review of the 2008 plan reveals relatively small areas may have been withdrawn. There are other areas identified as having important cultural and archaeological values with management restrictions. However, the management direction for these areas contains a lot of leeway. The authorized officer could approve a ground-disturbing project if they found it was in the “public interest” or if avoidance of adverse impacts to properties is “not feasible”, etc.

It appears that the majority of the 1,150,860 acres excluded from the current administration’s monument are now generally open for oil and gas drilling and uranium and potash mining. These areas are at risk for escalating disturbance, destruction, vandalism, looting and desecration.

In addition to losing protections, the excluded areas are also facing a loss of potential support for their safekeeping. When a monument is established, the managing agency has a justification for a larger budget and staff to work with the resulting swell of visitors and to increase resource protection.

That isn’t the case with the majority of the Bears Ears landscape. The news about the original monument designation, the machinations to reduce the monument and open up the eliminated areas to resource extraction have increased visitor use to the area. There is no indication that BLM or the FS is seeing increases in budget or staffing to work with Tribes and others to protect, educate, monitor, and enforce the law for the Bears Ears Cultural Landscape. Volunteers are trying to protect this area, but they don’t have the staff or authority to compel compliance with the law. Often they are only documenting the damage after the fact.

With the drastic unraveling of the original monument and its charter, areas are now again open for selling off rights to mine and develop to the highest bidder. This priceless landscape will once again be neglected due to lack of funds and staff to prevent looting, desecration, and damage from unmanaged off-road vehicle use. It’s a loss for Tribes, traditional practitioners, and for all of us.

Tribes and traditional practitioners are the first stewards of these landscapes. The land is often essential to their beliefs, practices, and well-being. I was taught by my grandmother and later by tribal and indigenous peoples that we don’t “own” a place; rather it holds us. If we take care of our places, they will take care of us.

The Obama administration’s declaration recognized that tribal collaboration was essential to the stewardship of the Bears Ears cultural landscape now managed by the federal government. The current administration has backed out of yet another commitment to Tribes despite how integral Tribes are to protect these areas and resources for generations to come. This administration’s actions contribute to the legacy of distrust between the federal government and Tribes. It also leaves the area vulnerable to predation.

The rights of tribal governments and traditional practitioners connected to Bears Ears must be defended. The federal government still has a trust responsibility to protect tribal rights and interests.

This current administration, like those before it, also has the responsibility to protect the cultural and natural resources for us all. The partnerships between federal land managers, Tribes, and other, which had been so carefully crafted during the creation of the original monument, but then discarded, must be restored. The public’s interest is best served by supporting tribal rights and stewardship of the Bears Ears cultural landscape. Bears Ears itself may withstand the onslaught of mining, vandalism, and looting, but we are all diminished by what is happening here.

Please join me in taking action to protect the Bears Ears cultural landscape. You can advocate for new legislation to expand the monument, work with tribal and partner organizations, and support litigation to restore the original monument.

Here are some key links to help you protect the Bears Ears cultural landscape:

See updates from www.bearsearscoalition.org

Support the Native American Rights Fund. See the Legal Review, Volume 42, No 2: Protecting Bears Ears National Monument at www.narf.org/news/legal-review.

Follow the Utah Dine’ Bike’yah on Twitter @UtahDineBikeyah

Look at the The Bears Ears National Monument Expansion Act (HR 4518) introduced by Rep. Ruben Gallego (D-AZ), which would expand the monument boundaries to 1.9 million acres recommended by the Intertribal Coalition. To communicate with your representative to back this bill, please visit www.supportsacredplace.org

Volunteer to protect and monitor Bears Ears. See www.friendsofcedarmesa.org.

Sonia Tamez is a Latina artist who has served as a federal agency tribal liaison, a long-term land management plan coordinator (for 18 million acres), staff and consultant for intertribal and native organizations, staff member for a SW Senator (on fellowship), on special assignment on the US delegation to the United Nations forum on Forests, board member for cultural, environmental and archaeological boards, and many other jobs in her long career. She continues to volunteer to support Tribes and indigenous groups.

More blog posts