By: Melissa Kay and Lily Cohen

January 26, 2026

Published as part of The Headwaters Report

This article will provide an overview of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC or Commission) hydropower licensing process, focusing on leverage points for Tribal engagement. Following a brief introduction on the relationship between Tribal Nations, hydropower dams, and FERC licensing, the first section provides a general description of FERC’s authority and structure, followed by a second section outlining the timeline of a FERC hydropower licensing process and how Tribal Nations can participate in these processes. The third section highlights several strategies for protecting Tribal rights and resources. The final section briefly addresses other important federal and state agencies involved in FERC licensing proceedings and how Tribal Nations may work with those agencies to accomplish their goals. This overview is not intended to discuss all the opportunities and challenges facing Tribal Nations in hydropower licensing processes, but instead to provide a starting point for Tribal Nations seeking to engage.

Introduction:

The same water resources that are sacred to Tribal Nations are often impacted by hydroelectric power projects such as hydropower dams and pumped storage projects. These projects have decimated salmon runs and disrupted other ecosystem functions on Tribal homelands by degrading water quality and blocking fish passage outright. Although hydroelectric energy has long been touted as a “clean” energy, hydropower projects have devastated Tribal Nations’ treaty-protected rights and resources—particularly salmon and other endangered fish species runs. Notably, fish runs on the Columbia, Snake, and Klamath Rivers in the Northwest plummeted after significant hydroelectric projects were built on those rivers. And over 1 million acres of Tribal lands have been flooded over 1.1 million acres by hundreds of dams built for hydropower and irrigation, displacing Tribal communities and destroying access to their traditional hunting and fishing grounds.

Hydropower project design has advanced to reduce some of these impacts, including by eliminating the need for dams, improving fish passage, and creating flexibility in dam management to ensure sufficient, consistent flows for all stages of the fish life cycle. Hydroelectric energy production does not inherently run counter to Tribal interests, and some Tribal Nations own and manage hydropower projects that provide electricity and revenue for their communities. But Tribal Nations have also spent decades advocating for protection of their Tribal resources in the face of unchecked public and private hydropower development in their watersheds and have consistently advocated for protection of their Tribal resources.

All non-federal hydroelectric power projects in the United States are permitted and regulated by FERC under the Federal Power Act (FPA).[1] These projects make up the majority of hydropower capacity in the country.[2] As sovereign governments with legal rights in FERC hydropower licensing processes, Tribal Nations can influence current management and operations and help shape the future of hydroelectric energy development in the United States.

Nearly 40% of all existing FERC licensed hydropower projects will be relicensed in the next decade.[3] Over the past several decades, relicensing has brought to the foreground many of the issues engrained in the early development of the federal hydropower permitting framework, including the complete exclusion of Tribal Nations from the original permitting decisions. As that regulatory framework has evolved to include Tribal involvement, Tribal Nations have engaged in successful campaigns to protect Tribal resources.

However, the process for hydropower licensing and relicensing is burdensome for Tribal Nations that seek to be involved. And recent changes eroding required environmental impacts analysis under the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA), as well as a push by the Department of Energy (DOE) to reverse FERC’s 2024 policy decision to deny preliminary permits on Tribal land that are applied for without Tribal consent, threaten to make it significantly more difficult for Tribal Nations to protect their natural and cultural resources in hydropower permitting processes.

Section 1: Overview of FERC

Under the FPA, FERC possesses the exclusive authority to grant licenses permitting private and municipal developers to construct and operate hydropower projects. Many hydroelectric projects in the country were constructed between the 1940s and the 1960s,[4] and those operating permits were typically for between 30-50 years. For the past several decades, the bulk of FERC’s work on hydropower has been in permit relicensing processes, even as new projects continue to be developed.

FERC’s approach to licensing decisions is shaped by balancing requirements that can provide Tribal Nations with pathways to protect their rights and resources. The FPA was originally enacted to establish a federal regulatory framework for hydroelectric power projects. In 1986, the Electric Consumers Protection Act amended the FPA to require FERC to consider not only power production needs, but also the interests of fish, recreation, and environmental quality. When making licensing decisions FERC is now required to balance its purpose of energy production with “equal consideration to the purposes of energy conservation, the protection, mitigation of damage to, and enhancement of, fish and wildlife (including related spawning grounds and habitat), the protection of recreational opportunities, and the preservation of other aspects of environmental quality.”[5] In its amended form, the FPA includes three significant sections for Tribal Nations—sections 4(e), 10(a), and 10(j). These sections, along with section 18, which deals with fishways, will be discussed in further detail below.

FERC operates as a federal agency made up of five commissioners who are appointed by the president. The agency is quasi-judicial, meaning its decision-making process is set up to resolve disputes among multiple parties, and those parties may challenge FERC decisions and seek review of FERC decisions by a federal court of appeals rather than going to a district court.

Because FERC operates as a quasi-judicial agency, it limits the communication that its decision-making staff can have with parties to a licensing proceeding. FERC’s goal in limiting communication is to ensure that all participants in a proceeding have access to the same information. In technical terms, this is called a restriction on ex-parte communication. This means that once a project proponent has submitted a licensing or relicensing application, FERC will restrict its staff from communicating with one party, without other participants present. Instead, FERC wants communication to be in writing and submitted to the publicly available docket.

All final decision-making authority technically rests with the commissioners. However, throughout a licensing process, lower-level FERC staff will make determinations and prepare documents, such as the environmental review documents under NEPA. Each project will have FERC staff assigned as project coordinators, and those project coordinators can answer procedural questions about the specific FERC process for that project. However, they cannot answer substantive questions, due to their “decisional” role once an application has been submitted.

Given the ex-parte communication constraints applied to FERC proceedings, it is important for Tribal Nations to know when and how they can communicate with FERC, as well as what resources are available to support Tribal engagement:

- For additional questions from Tribal Nations, FERC’s Office of External Affairs interfaces with Tribal governments.

- FERC’s Office of Public Participation can assist individual Tribal members with questions, and its staff are considered non-decisional.

- FERC also established a Tribal Liaison position. The Tribal liaison position is intended to educate the Commission and Commission staff about Tribal governments and cultures, to serve as a guide for Tribal Nations navigating Commission processes, and to ensure that consultation requirements are met.

- FERC has put together a Tribal Participation Guide for FERC Environmental Reviews resource that provides key information for Tribal Nations.

Section 2.1: How FERC Licensing Works

A project proponent can choose to follow one of three license processes: the Integrated License Process, the Traditional License Process, or the Alternative Licensing Process. Each process has different timelines, deadlines, and order of actions. The Integrated License Process (ILP) is the default, and this article focuses on the ILP framework, as defined in 18 C.F.R. Part 5.

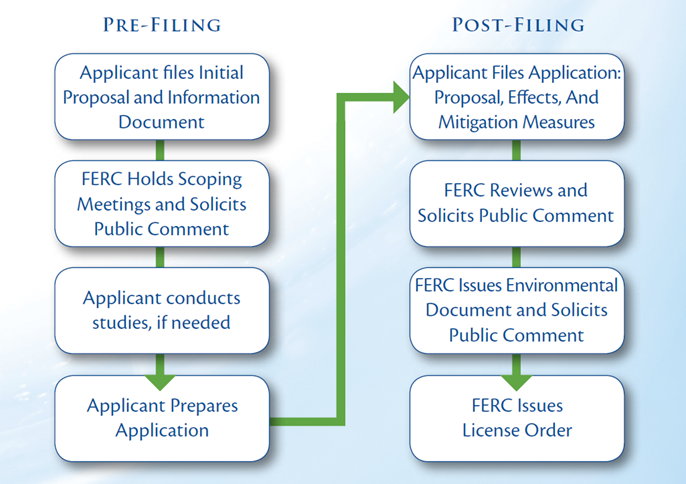

The formal FERC licensing process is divided into two distinct periods: pre-application and post-filing activity. The pre-application period can be viewed as the information gathering phase, while the post filing period is FERC’s decision-making phase.

The pre-application period begins when the project proponent submits a notice to FERC proposing a new project or initiating the relicense of an existing project. The process next includes a scoping phase and a study plan determination phase to understand the impacts of the proposed project. Once there has been a determination on the study plan, the project proponent undertakes a two-year study process. Throughout this period, Tribal Nations, agencies, and all other members of the public can comment on study reports and otherwise engage in study development.

After completing the studies, the project proponent files a license application, which signals the start of the post-filing period. Once the application has been filed with FERC, Tribal Nations, agencies, and members of the public can submit proposed license conditions that create the rules for how the project proponent will construct and operate the project. FERC considers these license conditions when reviewing the project but is only obligated to accept those that are mandatory under sections 4(e) and 18 of the FPA. FERC then begins its environmental review under NEPA, which relies on the project proponent’s studies and information included in the application. The environmental review must include consideration of the draft license conditions. Next, FERC issues a final license order deciding whether to issue the license. If FERC does issue a license, the final order will include the conditions on that license.

In addition to the formal process discussed above, settlement negotiations can occur at any time before FERC issues a final license order.[6] Settlement negotiations allow the project proponent and other participants to come together and collaborate on an agreement for how the proposed project will operate. By engaging in the settlement process, Tribal Nations can have more influence on the license application and the conditions placed on the proposed project. A project proponent has an incentive to participate in the settlement process because certain federal and state agencies that have the authority to issue mandatory license conditions may come to the table for a more mutually beneficial outcome. Those agencies will be discussed in Sections 3 and 4, below. In general, FERC has a policy favoring settlement because it can resolve conflicts in highly contested hydropower licensing proceedings. However, Tribal Nations also face ongoing challenges with settlement inclusion and settlement enforcement.

A Recent Settlement on the Skagit: In December 2025, after over seven years, a comprehensive settlement was reached amongst the three Skagit River Tribes, Seattle City Light, the State Departments of Ecology and Fish & Wildlife, and federal regional leaders at the National Marine Fisheries Service, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Indian Affairs and National Park Service Seattle for a new 50-year federal hydroelectric dam license for the City of Seattle’s three dams on the Skagit River. The settlement will “guide how Seattle will invest approximately $4 billion dollars in the Skagit River watershed for estuary and mainstem habitat restoration, flow protections for salmon at all life stages, adaptive management and scientific research, and fish passage.” (Statement from Chairman Edwards, Swinomish Indian Tribal Community.)

For each project, FERC creates an online docket that makes available all the applicant submissions, responses from FERC, and comments from Tribal Nations, agencies, any other participants, and the public. The docket system is difficult to navigate, unfortunately, but FERC provides instructions on how to file a comment. Alternatively, Tribal Nations can submit comments by mail.

Section 2.2: Tribal Engagement in FERC Proceedings

FERC’s Tribal consultation policy recognizes its trust responsibility to Tribal Nations.[7] The Policy requires the Commission to “assure that tribal concerns and interests are considered whenever the Commission’s actions or decisions have the potential to adversely affect Indian tribes, Indian trust resources, or treaty rights.”[8] And in addition to the provisions of the FPA, FERC licensing processes must also comply with other federal laws, including NEPA, the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), the Clean Water Act (CWA), and the Endangered Species Act (ESA), each of which have its own Tribal consultation requirements.

During the pre-application phase, FERC is obligated to initiate consultation with affected Tribal Nations.[9] Tribal Nations also have the right to request government-to-government consultation by contacting FERC’s State, International, and Tribal Affairs Division, the point of contact listed in a letter or notice they received from FERC staff, or FERC’s Commissioners.[10] FERC outreach “extends both to federally recognized Tribal Nations located in the project area and to those Tribes with a historic interest in the project area,” and the consultation can address NEPA, NHPA, and other relevant analyses that FERC must consider in its decision-making.[11]

However, FERC’s restrictions on ex-parte communication create a major challenge for Tribal Nations seeking government-to-government consultation once an application has been submitted. As noted in Section 1, because FERC operates as a quasi-judicial agency, FERC limits the communication that its decision-making staff can have with Tribal Nations and all other parties to a licensing proceeding.

And even before a project proponent submits a final license application, FERC’s restrictions on consultation are poorly defined. Even in the pre-application phase, FERC will sometimes refuse to consult on issues that it believes are likely to be disputed later in the process. FERC’s policy does not define when it will deny a consultation request in the pre-application phase and instead decides on a “case-by-case” basis. The lack of guidance makes it difficult to predict when FERC may refuse to consult about an issue.

When to Seek Government-to-Government Consultation? It is important for Tribal Nations to be strategic about when they seek government-to-government consultation with FERC to make that consultation most effective. FERC typically does not intervene during the pre-application stage except as required by regulation to resolve disagreements and amend the approved study plan as appropriate, after the initial and updated study reports are filed. However, situations may arise in the pre-application phase where the project proponent is taking actions that actively harm Tribal interests. If the project proponent is acting in a way counter to a Tribal Nation’s interests and refusing to engage with the Tribal Nation, the Tribal Nation may consider requesting consultation with FERC.

Once a project proponent submits a final license application, FERC will no longer conduct government-to-government consultations with Tribal Nations off the record. FERC may agree to meet with a Tribal Nation, but anyone else will be allowed to come to the meeting, and FERC will issue a transcript or summary of the meeting for the public docket. However, Tribal Nations may still have off-the-record discussions with decisional FERC staff if they participate in the NEPA process as a cooperating agency. Regardless of the phase of the process, anyone can continue to ask FERC staff about procedural matters.

In addition to consultation, at every step of a FERC proceeding Tribal Nations can submit comments on the record. Tribal Nations should submit comments in response to specific documents during their relevant comment periods, but they can submit comments on the record at any point. Submitting comments on the record is critically important because FERC will respond to comments and make its decisions based on the information in the record. The Commission won’t necessarily raise an issue independently; for example, if a project proponent is failing to follow study requirements laid out in its approved study plan. There will typically be at least seven comment periods throughout the process. This provides an opportunity for Tribal Nations to participate in the licensing process but also requires substantial capacity.

Each licensing process will have different nuances that make engagement at individual stages particularly critical. Here we highlight three stages that are consistently important:

- Study Plan.

FERC has its own requirements for studies, but by engaging in the process, Tribal Nations can seek to have additional studies included in the FERC-approved study plan, such as environmental, cultural resources, and economic studies. For example, FERC will not independently require studies considering climate change, its impact on future water flows, and how climate change might impact fish or the economic viability of a project.[12] This remains true even though changing weather patterns are impacting the reliability of hydropower projects. However, Tribal Nations can submit suggested studies on these topics and work with the project proponent to include them in the proposed study plan.

The project proponent submits a study plan to FERC in two phases: first a proposed plan that lays out the scope of the project proponent’s pre-application studies forming the basis for FERC’s environmental and cultural reviews of the proposed project, and second, a revised study plan that responds to comments. Commenting on both phases of the study plan provides an opportunity for Tribal Nations to shape the studies.

During the study period FERC often authorizes the project proponent to initiate informal consultation with Tribal Nations and other requisite state and federal agencies under Section 106 of the NHPA and Section 7 of the ESA, although FERC remains legally responsible for all findings and determinations.[13] Tribal Nations are not required to consult with the project proponent, but they may propose natural and cultural resource studies on the basis of FERC’s federal obligations.

- Intervention and/or Participation as a Cooperating Agency under NEPA.

Tribal Nations and all other parties must formally intervene in a licensing proceeding to challenge a final FERC licensing decision. Intervention is required both to bring an agency rehearing challenge, and to bring a challenge in court. Intervention must occur during the 60-day comment period after an applicant submits a final license application.

A Note on Process: If a Tribal Nation is authorized by the Environmental Protection Agency to issue water quality certifications under Section 401 of the CWA, it may file a timely notice of intervention rather than a motion to intervene. See Section 3, Part B below for more information on the role of Section 401 certification in FERC hydropower processes.

Challenging a FERC decision starts with a request for an agency rehearing after FERC issues a final license order. If FERC denies the rehearing request, then an intervenor can appeal the decision to court.

Generally, intervention comes with no additional obligations other than a requirement to provide all other intervenors with copies of any documents filed on the FERC docket. However, due to the ex parte communication restrictions, FERC prevents agencies acting as cooperating agencies in the NEPA process, including Tribal Nations, from also intervening in the proceeding. Despite this general rule, in some instances, FERC will allow a Tribal Nation to participate as both an intervenor and a cooperating agency. However, Tribal staff working on the intervention must be separated from Tribal staff working on the environmental documents, and they cannot exchange information. FERC has discretion to approve or deny such an arrangement. Participating as both an intervenor and a cooperating agency gives Tribal Nations the maximum opportunity to advocate for their interests in the permitting process, but it requires significant capacity that many Tribal Nations do not have.

- License Conditions.

License conditions place requirements on how a project proponent must construct, operate, and maintain their facility. License conditions are the primary method FERC uses to achieve its obligation to balance power and non-power values. FERC issues these conditions when it issues a license. Tribal Nations and all other participants can suggest conditions during the 60-day comment period after an applicant submits its final license [14]

License conditions will become the final rules that can serve to protect Tribal interests. For example, a license condition could protect fish passage by requiring fish screens on the intake or requiring ongoing fish monitoring. Some conditions can protect both fish and water quality through limits on the amount of flow that can be diverted or requiring a minimum amount of flow to be released. Additionally, for projects that create a reservoir, FERC typically requires the project proponent to construct recreational facilities such as a boat launch. Tribal Nations should submit proposed license conditions to ensure that the project proponent and FERC consider their interests and should engage with relevant agencies with license conditioning authority to advocate for conditions that protect Tribal interests.

License Conditions Can Lead to Salmon Restoration: In one of the most prominent campaigns to protect Tribal fishery resources through FERC relicensing, the Yurok, Karuk, Hoopa Valley, and Klamath Tribes fought for decades to restore salmon to the Klamath River and its tributaries. This effort ultimately led to the decommissioning and removal of four hydropower dams on the Klamath River. FERC issued the original dam licenses in 1954 which allowed the project to completely block salmon from returning to their spawning grounds in half of the basin. In the early 2000s, the project owner, PacifiCorp, filed a relicensing application. Right before the relicensing application was filed, the Klamath River experienced one of the largest fish kills recorded in United States history in 2002. After integrating recommendations from the Tribal Nations along the Klamath River, FERC’s draft license conditions demanded new provisions for fish passage.

PacifiCorp determined that implementing those conditions would require operating the project at a loss, which led the parties to begin settlement negotiations. Those negotiations eventually led to a revised proposal for the decommissioning and removal of dams. The dams were finally removed from the river in October 2024, freeing 420 miles of the Klamath River and its tributaries in California and Oregon. Since the dam removals, the Tribal Nations have seen the salmon return.

Amy Bowers Cordalis, Executive Director of the Ridges to Riffles Indigenous Conservation Group and former General Counsel for the Yurok Tribe, recently published a book on her family’s contributions to this campaign to restore the salmon, entitled The Water Remembers.

Section 3: Avenues for Protecting Tribal Rights and Resources

Despite the various requirements to consider Tribal interests at different stages of a FERC hydropower licensing process, the barriers to entry are high, and there are significant gaps in the statutory and regulatory framework that prevent Tribal Nations from protecting their rights and resources. Engaging in a licensing process requires substantial capacity and technical expertise. And even when Tribal Nations possess the necessary resources, it is difficult to know how to put them to efficient use. This section covers four opportunities that Tribal Nations should consider when deciding how to engage.

- Mandatory Conditions Applying to Projects Located within a Federal Reservation

Section 4(e) of the FPA[15] places additional requirements on FERC when a proposed hydropower project is located within a federal reservation, including Tribal lands held in trust by the United States, or most federal public lands. To license a project on Tribal land, FERC must first find that the license will not “interfere or be inconsistent with the purposes for which the reservation was created or acquired.”[16] Second, FERC must include all the license conditions that the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) determines are necessary for the “adequate protection and utilization of such reservation.”[17] The BIA has this authority because it is the agency within the Department of the Interior that manages Tribal trust lands on behalf of the federal government.

The BIA does not possess veto power for a hydropower license, but its conditions are mandatory. And unlike other participants, agencies with 4(e) authority can formally dispute the study plan determination, giving these agencies more sway at an earlier stage in the process.[18] The BIA Hydropower Compliance Program is the office that develops and imposes conditions deemed necessary for the adequate protection of Tribal rights and resources. Tribal Nations should reach out to this office as early as possible in the process to communicate the conditions that are necessary to protect their interests. Once a license has been issued, the BIA is also responsible for monitoring the project to ensure the final license conditions are implemented sufficiently to protect Tribal interests. The BIA also has limited funding available for Tribal technical support.

An additional challenge faced by Tribal Nations in Alaska is that only one out of 229 federally recognized Tribal Nations in the state has a reservation. This limits the potential for the 4(e) mandatory license conditions to be applicable for most Alaska Tribes.

Looking Forward: There has been at least one attempt to propose legislative reform shifting 4(e) mandatory conditioning authority away from the Department of the Interior and to the relevant Tribal Nation. The reform package did not pass, but these reforms remain potential solutions to some limitations that face Tribal Nations in FERC hydropower proceedings.

- Leveraging Water Quality Certification under CWA Section 401(a)

FERC may only issue a hydropower license if the project is certified by the state or Tribal Nation with jurisdiction over the affected water body under CWA Section 401. If a Tribal Nation has “Treatment as a State” (TAS) authority under Section 401, FERC must include in its license any conditions that the Tribal Nation requires to certify that the project will not violate the applicable water quality standards.

More information on how a Tribal Nation obtains TAS jurisdiction under the CWA and what authority that grants Tribal Nations is available at An Introduction to the Clean Water Act.

If a Tribal Nation also has its own water quality standards under CWA Section 303, it may place conditions on the hydropower project based on those Tribally defined water quality standards, which may be set to protect ceremonial uses and culturally significant resources. A certification may establish a minimum flow schedule or flow storage or require certain types of fish passage. As with FPA Section 4(e) or 18 conditions, these are mandatory, and FERC may not amend or delete them from the license.

- Protecting Properties of Traditional, Religious and Cultural Significance through NHPA Section 106

Prior to issuing a license, FERC is required to conduct an analysis under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA).[19] This includes consulting with Tribal Nations to identify potentially affected properties of traditional, religious, and cultural significance, assessing the adverse effects of the proposed hydropower project on those properties, and developing and evaluating alternatives that could “avoid, minimize, or mitigate” those effects.

The project proponent assists FERC in meeting its obligations under Section 106 by following the applicable procedures.[20] However, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation’s Handbook on Consultation with Indian Tribes in the Section 106 Review Process states that “[e]ven when an Indian tribe agrees to coordinate with an applicant, the federal agency remains responsible for ensuring that the Section process is carried out properly, meeting the letter and spirit of the law, as well as resolving any issues or disputes.”

Under Section 106, FERC recognizes that Tribal Nations possess “special expertise” regarding the evaluation of these properties and how to resolve adverse effects to them. Participating as a consulting party in the Section 106 process is one way that Tribal Nations can seek to insert conditions or requirements into a hydropower license or can pursue an alternative binding commitment, such as a memorandum of agreement. Investing in the Section 106 process may also provide a Tribal Nation with more leverage to bring into settlement discussions.

- Developing Comprehensive Plans for Affected Watersheds

Under Section 10(a) of the FPA,[21] FERC is required to consider how a proposed project fits within a comprehensive plan for improving or developing a waterway based on equal consideration of both power and non-power values.[22] This includes the requirement to solicit and consider license conditions from Tribal Nations affected by the project.[23] Proposed licensing conditions submitted based on solicitation under Section 10(a) are not afforded any deference, but this clause provides a statutory mandate for Tribal involvement in FERC hydropower licensing processes. In addition, the project proponent’s application must include an explanation of whether the project would comply with any relevant comprehensive plan. If a Tribal Nation determines that the project would be inconsistent with such a plan, the project proponent must include that determination.[24]

Building on the statutory and regulatory language, FERC’s Tribal consultation policy explicitly requires the Commission to consider any comprehensive plans developed by Tribal Nations or inter-Tribal organizations for improving or conserving an affected waterway affected by the proposed project when evaluating a proposed hydroelectric project.[25] Thus, Tribal development of comprehensive plans for a waterway can help shape FERC’s analysis of a proposed project.

This section is far from exhaustive, and there are other ways for Tribal Nations to protect their resources during FERC proceedings that are not explored in depth below, including seeking protection through a “rights of nature” framework.

Section 4: Opportunities to Leverage Other Agencies

While FERC has the final say on whether to issue a license, other agencies have significant authority over the license conditions that FERC must include in a license. Tribal Nations can engage and coordinate directly with those agencies to share knowledge, and advocate for license conditions that protect Tribal interests.

- Section 18: Mandatory Conditions Applying to Projects That May Affect Fish Passage

National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) have the authority to issue mandatory license conditions that ensure “fishways” to ensure fish can safely travel up and downstream through the project.[26] These conditions are often called “fishway prescriptions” or “section 18 prescriptions,” in reference to a section of the Federal Power Act. [27] FERC does not have the discretion to change or reject these. [28]

- Section 10(j): Requirement to Solicit Condition Recommendations from Other Agencies

Under Section 10(j) of the FPA,[29] FERC is required to include in any hydropower license conditions that “adequately and equitably protect, mitigate damages to, and enhance, fish and wildlife” affected by the project. FERC is required to give deference to recommendations for these conditions from NMFS, USFWS, and State fish and wildlife agencies. The Commission is only allowed to reject these recommendations if it thinks they are inconsistent with the Federal Power Act or another law. [30] FERC is also required to work with agencies to resolve disagreements about their 10(j) recommendations, which may include convening a meeting or technical conference. If an agreement cannot be reached, FERC will publish its final decision rejecting the recommendations.

[1] 16 U.S.C. §§ 791 et seq.

[2] Hydropower Primer: A Handbook of Hydropower Basics, Office of Energy Projects/Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Section 1.1 (Feb. 2017).

[3] Connor Nelson, Hydropower at Risk, National Hydropower Association, 3 (2025).

[4] Christy McCann, Dammed If You Do, Damned If You Don’t: FERC’s Tribal Consultation Requirement and the Hydropower Re-Licensing at Post Falls Dam, 41 Gonz. L. Rev. 411, 417-18 (2006).

[5] 16 U.S.C. § 797(e).

[6] 18 C.F.R. § 385.602. It is best practice to reach a settlement agreement before FERC undertakes its environmental assessment process. This allows the alternative reached in the settlement agreement to be included in the environmental assessment.

[7] See 18 C.F.R. §2.1(c).

[8] Id.

[9] 18 C.F.R. § 5.7.

[10] Tribal Participation Guide for FERC Environmental Reviews, Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (last updated Jan. 26, 2025), https://www.ferc.gov/tribalrelations/NEPA#_restrictedexparte.

[11] Id.

[12] See, e.g., Merced River Hydroelectric Project, P-2179-000.

[13] See 36 C.F.R. §800.2(c)(4); 50 C.F.R. §402.08.

[14] 18 C.F.R. §5.23(a).

[15] 16 U.S.C § 797(e).

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] 18 C.F.R. §5.14.

[19] 16 U.S.C. §§ 1451-1464; 36 C.F.R. §800, Subpart B.

[20] 18 C.F.R. § 380.14.

[21] 16 U.S.C. § 803(a).

[22] Id. at (1).

[23] Id. at (2)(B), (3).

[24] 18 C.F.R. §5.18(d).

[25] 18 C.F.R. §2.1c(k).

[26] 16 U.S.C. § 811.

[27] Section 1701(b) of the Energy Policy Act of 1992, Pub.L. 102-486, Title XVII, § 1701(b), Oct. 24, 1992, 106 Stat. 3008 (“That the items which may constitute a ‘fishway’ under section 18 for the safe and timely upstream and downstream passage of fish shall be limited to physical structures, facilities, or devices necessary to maintain all life stages of such fish, and project operations and measures related to such structures, facilities, or devices which are necessary to ensure the effectiveness of such structures, facilities, or devices for such fish.”).

[28] Am. Rivers v. FERC, 201 F.3d 1186, 1210 (9th Cir. 1999).

[29] 16 U.S.C. § 803(j).

[30] 18 CFR § 5.26(b).

More blog posts